In recent years, the relative housing cost in Greece has risen rapidly. According to Eurostat data, Greek renter households spend around 37% of their household income on accommodation ─the highest percentage among EU countries.

Around 1 in 3 households living in cities spend even more, actually more than 40% of their income, on housing ─also the highest percentage in Europe. 3 out of 4 tenants aged 18 to 44 say that they experience stress or anxiety as a direct result of the rent they have to pay. People's experiences from house hunting in Athens, usually written in a tone of desperation, capture the same picture.

But how did we come to having the most expensive housing in Europe in terms of income? One explanation to that could be the sharp decrease in income. From 2009 to 2014, Greeks lost more than 40% of their disposable income. During that time, the numbers of tourists in cities and on the islands were rising. Landlords found new ways to make better use of their properties, such as short-term rentals, which in turn affected real estate prices and rents.

Yet, even before these developments, Greece was a country with not so much of a housing policy. So, when the economic crisis hit, housing policy fell apart: In 2012, the Workers' Housing Organization (OEK), the government entity operating mass housing projects across the country, was abolished without any provision for a successor body.

Lately, the housing policy debate has reopened. Stakeholders acknowledge that there is an actual problem to be addressed and that it has a wider impact on the demographic profile of the country, among others. The government has adopted measures that remain to be implemented, and the opposition parties have also put forward their proposals. But what might a modern and effective housing policy in Greece look like?

To answer this question, one must first look back on the housing policy that Greece had in the past, its footprint, inefficiencies, but also on how and why it came to a close.

The "sudden death" of the OEK

On 12 February 2012, in a dramatic parliamentary session, with the Attikon and Apollo cinemas under fire on Stadiou Street, the L. 4046/2012 was adopted. This law, which was in fact the second bailout agreement between Greece and its creditors (EU-IMF), a lengthy 574-page document with many annexes, like the previous memorandum, provided for significant cuts and hundreds of changes in the way the State had been operating.

Its adoption secured much-needed funding and "unlocked" the debt reduction scheme known as the PSI. This was perhaps the darkest moment of the Greek crisis. After experiencing a 15% loss of its GDP in just a couple of years, the country was in such turmoil that few had the luxury of taking a closer look at a brief passage in Annex 5 of the Law, which stated that, in order to reduce non-wage labor costs, "we will enact legislation to close small earmarked funds engaged in non-priority social expenditures".

The two "non-priority" agencies were the Workers' Hearth Organization and the Workers' Housing Organization. The first body, the smaller of the two, covered the "post-work care" (economic holiday programs and discount vouchers for theaters and other attractions), and also supported the operations of trade unions.

The second body, the ΟΕΚ, implemented the State housing policy for wage-earners. In fact, it was the organization that had been running mass housing projects across the country for the past sixty years, including construction projects or financial aid for home buying.

In 2012, when the OEK was closed down, the media and politicians had their attention on other cuts under the second bailout agreement, like pension cuts. Therefore, apart from that small reference in the agreement itself to "reducing non-wage labor costs", there is no other evidence to support the decision to close down the OEK.

Why did Greece and its creditors eventually decide to close down the OEK at that time? If one asks that question to people who were involved with the organization at the time, he/she gets varied answers: "Perhaps it was felt that the State should not operate as a bank or a construction company"; "At the time, there was no pressing need for housing, as the rate of home ownership in Greece was quite high and the crisis had kept real estate prices and rents low"; "Perhaps it was believed that public works would give rise to corruption or that the organization was in fact competing against the private sector"; "According to hearsay, the memorandum agreement was about EUR 300mio short, an amount roughly equal to the organization's reserves at the time".

In April 2013, the OEK was formally absorbed by the then OAED (now DYPA). Its absorption actually led to the cessation of all new activity. It stopped granting new loans, providing interest rate subsidies on mortgages or allocating rent allowances. It also ceased all activity of planning new settlements and house construction. To this day, the organization has mainly dealt with already planned projects or projects pending before 2012: following up on loans already granted and completing projects that had already started.

The land-for-apartment exchange system: A system designed for "small players"

But how did Greece's housing policy come to naught? Although the Greek government did have some form of housing policy, this was never adequately strong or organized, compared to other countries of Northern and Central Europe. How did the State assist Greeks in purchasing their own home? "In Greece, no government had ever shown a serious interest in housing", notes Nikos Triantafyllopoulos, Assistant Professor of Urban Planning and Real Estate Management at the School of Engineering, University of Thessaly. "Indeed, we had the OEK and some attempts had been made to establish housing banks, such as Ktimatiki and Stegastiki, as a way to facilitate housing loans. However, housing policy was mainly pursued in an indirect way, through the promotion of the land-to-apartment exchange system, but also through trespasses to land and subsequent legalizing arbitrary buildings. Social housing, although it existed too, was never developed to such an extent as to make a significant difference".

Thomas Maloutas, Professor of Human Geography at Harokopio University, shares a similar view. "In Greece, the development model was quite different from that applied in the European industrial countries, where housing was seen as a way to ensure the availability of workers", he says. "In Greece, the great post-war migration from the countryside to the cities was not exactly a sign of industrialization: those who left the countryside could not easily find work in the cities either ─besides, almost as many migrated abroad. Therefore, neither the State nor employers were particularly interested in keeping workers happy and in sufficient numbers.

In light of this, housing became more of an individual or family concern rather than a public concern. People had to build their own homes, pretty much with their own hands. Moreover, the political system made sure that the housing sector would be a field that would favor small players: small landlords and small developers. As far as the early 1990s, it was very difficult for banks to get a foot in the housing sector. On the other hand, small developers were protected from the entry of large construction companies into the market. Actually, big developers did not have a higher profit margin than small developers on a per-unit basis. Therefore, large construction companies, which could have carried out larger ─either state-funded or private─ housing projects, were more or less absent from the housing sector".

The land-for-apartment exchange system, the so-called Antiparochi, was a transaction that allowed many Greeks to purchase their home without having to pay in cash. It largely determined the development of Athens and other Greek cities as well. "Builders, Housewives, and the Construction of Modern Athens" (2021), a documentary film based on the book of the same name by Ioanna Theocharopoulou ─the production and publication of which was funded by the Onassis Foundation─ chronicles the era of Antiparochi, from the 1950s onwards. It traces several personal stories, mostly of builders and contractors and their wives. In the documentary, one "builder" recounts how he carried mud with a tin can from the ground floor to build the sixth floor of an apartment building. One of the "housewives" recalls how she helped her husband build their own house ─they had to hurry to get it ready before winter came. At the same time, it was not uncommon for builders to make their own little esthetic tweaks to the building plans prepared by the engineers ─a typical example is wall patterns outside the bathroom windows.

These personal stories about how the city was actually built largely reveal the absence of significant central programming. Yet, they also highlight the distinctiveness of Athens, at least against the European context. "While shooting this documentary, all our prejudiced views of Athens were overturned", says Tasos Laggis, who co-wrote the script and directed the film together with Giannis Gaitanidis. "Being almost 50 years old, I grew up hearing about how the 'antiparochi' system had destroyed the cities and how 'unsightly' Athens is. With the experience we gained from shooting this documentary, all this prejudice was overturned. We met people who were then young and crushed by post-war poverty. They had the same needs that we have today: to live with their family in a solidly-built house with safe hygiene conditions and have some prospect of advancement in their lives. They started off with that dream, with those needs in mind, and they made it true. This perspective of Athens as a city that was built with those feelings and desires in mind was a great surprise to me. Athens cannot be compared to cities in Turkey and the Middle East, nor to European cities like Rome or Paris. It is something unique, and this uniqueness ─perhaps because it is so familiar to us─ has become, in a way, invisible".

On the other hand, any government housing measures were limited in scale and were always applied on the sidelines ─they rarely drove urban development or changed it effectively. What's more, they only addressed specific groups of the population.

Some well-known measures were taken to provide land for refugees from Asia Minor after the population exchange in 1922; refugee settlements were built in many Greek cities (the Public Enterprise for Urban Planning and Housing, which successfully redeveloped the refugee areas of Tavros, also ceased to operate in 2010). The Greek government also arranged for the accommodation of a certain number of students in student residences, provided housing to the homeless, and, until recently, to refugees soon after they had obtained asylum status.

What was the OEK?

Wage-earners were ─by far─ the largest group for whom the Greek government took some housing measures. The OEK, an organization that had operated since 1954 and for 58 years, collected from IKA (Social Security Institute) a small part of the employer's contributions (it was 0.75% when it was closed down) and the employees' wages (1%) in order to carry out housing programs. It was therefore a self-financed agency, meaning it did not burden the state budget, as its overall activity, including its staff salaries, was financed by employee and employer contributions.

In the years before it was closed down, the amount of such contributions was substantial, totaling close to EUR 650mio per year, but in fact, IKA paid out to OEK much less, often less than half of that sum. When the OEK was closed down in 2012, the employers' contribution was abolished, and in 2020, eight years later, the employees' contribution was abolished as well.

The OEK was a rather unusual organization within the Greek public sector. Before it was closed down, its staff consisted of 730 employees: 200 civil engineers, architects, surveyors, agronomists or geophysicists, and 100 economists, mathematicians, or accountants. Adding to that number of contract workers and trainees under work experience programs, the OEK's staff had at one point reached 1,000 employees in local offices across the country.

The ΟΕΚ was not unusual if seen in a European context. The only unusual thing about it was that its scope of activity was relatively limited compared to equivalent organizations across Europe. For example, more than 20% of all dwellings in Austria and the Netherlands is operated and managed by equivalent agencies (using very different models). All such organizations in Europe are members of Housing Europe, a confederation of social housing providers, and operate almost 25 million dwellings. Greece participates in Housing Europe through Major Development Agency Thessaloniki SA, which joined the confederation recently, after having published a study on housing in 2020.

As is often the case with the Greek public administration, publicly available data on the activity of OEK are scarce. According to data made public by the OEK from time to time (which are not properly documented), a total of 700,000 households had received financial aid to purchase or rent a house during the agency's operation: 100,000 households took out a loan to buy a turnkey dwelling, 362,000 took out a loan to build a house, 238,000 took out a loan to repair their house and 100,000 (or possibly more) benefited by a rent subsidy totaling between EUR 1,000 and 1,200 yearly. Similarly, around 500 social housing settlements are currently occupied by around 50,000 households.

The OEK was giving away more loans than it was building houses. Loans and allowances usually accounted for more than 70% of the organization's expenses. But this was not always the case. For example, after 2007, when families with three children obtained the status of large families, all employed parents of families with three children automatically became eligible for a housing loan. Loan expenses suddenly increased by EUR 160-195 million per year, and the OEK's loan-related expenses surged to 95% within two years.

Rent allowances in the mid-2000s cost more than EUR 150 million per year. However, at that time interoperability among public agencies was rare, which meant that cross-checking beneficiary data was rather difficult. Employees of the OEK argue that "the cross-checking process may not always have been exhaustive". In 2012, however, Greece was left without any rent allowance for five years up to 2017. Then a new, lower allowance was introduced as a term of the bailout agreement and is still allocated today by the Organization of Welfare Benefits and Social Solidarity (OPEKA).

Compared to the total number of dwellings in the country, those built by the OEK were rather few and therefore were not crucial for the development of Greek cities. But they did leave their own imprint, especially in smaller towns. These properties were usually built far from the center, therefore helping indirectly in the expansion of cities to a certain direction. A number of utilities, such as electricity or sewerage, were installed in several areas of Greece in order to serve the beneficiaries of the OEK. As soon as water, electricity, and sewerage were available, many more people would construct their own houses in the nearby areas.

The former OEK would manage the land (in some cases proceeded to acquire it), ensured it was entered in the urban plan if located outside the city limits, prepared a town-planning study, organized a call for tenders for the construction, and supervised the works. Then, the beneficiaries were selected through a draw and the OEK set the price that they would have to pay.

The OEK dwellings, usually measuring 80 to 130 sq.m. in two or four-storey buildings, are located in settlements all over the country. Although the two largest, by far, settlements built by the OEK are in Attica, the majority of social housing properties are located outside the Attica region.

The Greek version of social housing focused almost exclusively on ownership and owner-occupancy. In most Central and Northern European countries, social housing properties are usually available for rent, creating a kind of parallel market that "competes" with free-market rents ─probably contributing to their lowering as well. Moreover, the rented social housing market creates a stock of social housing properties, which the State can make available, at below-market rent, to those who are eligible at any given time. In Greece, social housing was given to a beneficiary for a low price, and after paying it they became the owner, regardless of their financial situation later on.

Therefore, the timing of the draw for the beneficiaries was of vital importance. For the purposes of this article, several of our interviewees described sarcastically this period as "a great feast" where "all State authorities would make an appearance".

But how much would the beneficiaries ultimately pay for their new home? This is something they would find out after a long time. After the draw, the process of calculating the cost of construction and setting the price of each dwelling began. The OEK staff factored in the cost of the land and of the construction of the settlement and the dwelling and calculated a flat cost per square meter for the residents of each settlement. In the 2000s, this cost was usually close to EUR 400, although there were settlements that charged much more, even more than twice as much. It was a time-consuming process. Calculating the cost could take several years and, in the meantime, the beneficiary paid a monthly sum in consideration of the cost pending determination. It was not uncommon for beneficiaries or settlers' associations to claim that their house or settlement suffered from poor workmanship and to claim a lower sum after they had moved into the house or settlement.

Over the past decade, the few former OEK employees (and, proportionately, even fewer engineers) who have remained in the DYPA have essentially only dealt with pending files. From the nature of the arrangements put in place at the end of the last decade, it can be gathered that the management exercised by the agency was not always ideal. Five years after OEK's closing down, in 2017, a maximum price per square meter was set for settlements that had not yet been invoiced and very favorable arrangements were announced for those still in debt.

Many of the loans of the OEK were non-performing loans. In 2018, NPLs were refinanced under very favorable terms including a haircut on interest accrued but not paid. The question of how the rather large assets of the former OEK are to be put to good use remains: according to unofficial estimates, these are areas of at least 450 hectares across Greece, usually coming from donations by Municipalities or Regions, the very large majority of them outside the city plan.

A village from the future

There is a piece of the Greek housing policy that is of particular interest today. North of Athens, in the suburb of Pefki, lies the Iliako Chorio (Solar Village), namely 435 dwellings, arranged in two, four, and six-storey buildings. This is the second largest settlement of the OEK, after the 2,300 dwellings of the Olympiako Chorio (Olympic Village). The Solar Village was designed between 1978 and 1981 by the firm of the architect Alexandros Tombazis and constructed by 1989 in such a way that the buildings would be energy-efficient in many pioneering ways.

In the 1970s and 1980s, climate change was nowhere in the horizon and we were a long way from today's subsidies for improving the energy efficiency of buildings. But then the world had just experienced two major oil crises. "The Solar Village was a pilot project in the field of 'solar architecture' as it was originally called, or 'bioclimatic design', as we call it today," says the architect Akis Tilemachou, who is now an associate at the Tombazis firm. In the "village", insulation systems coexisted alongside state-of-the-art "active systems" designed to provide heating and hot water to the dwellings while saving energy. At that time, technologies such as decentralized heat pump systems, air collectors, flat water collectors, seasonal thermal energy storage with water collectors, and a large water tank with a volume of 600 cubic meters were used for the first time in Greece.

These "active systems" were designed as a potential answer to the oil crises: with more energy-efficient homes, people were less dependent on the price of oil and the OPEC cartel. In fact, there was a broader interest in how well pioneering energy-efficient homes would work: the German Ministry of Research and Technology paid most of the cost of the study for the Solar Village. On the Greek side, researchers at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki measured the performance of the systems in the first few years after their commissioning.

A walk around the Solar Village today shows that most of these systems do not work as designed ─some never did. Most of the solar panels on the rooftops are damaged. Others have long been removed; the iron fittings on which they rested are now empty and the residents have attached conventional solar water heaters to some of them. One finds discarded insulation materials here and there. Eventually, in 2019, the Solar Village did what it theoretically did not need to do: it connected to the natural gas grid.

But why, even though the original idea behind the construction of the Solar Village became more and more relevant over the years, the village itself seemed to abandon it? According to the first evaluations conducted by the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, residents, although trained on the systems that had been installed at the time, found it difficult to operate them properly. They would put furniture on the southern walls, leaving no "air" for the thermal energy storage walls in some of the buildings of the settlement, therefore, in the winter, the houses were colder. "If shutters are closed or awnings were down in the 'greenhouse' space during a winter day, or furniture or objects blocked the sun rays from reaching, say, the water tank, because the family needs for space increased, there will inevitably be a decrease in the expected heat gain", explains Akis Tilemachou.

On the other hand, how easy was it for the people who lived there to monitor all those strange and demanding systems while going about their business and their lives? And, as these technologies improved, why didn't the systems get upgraded? "Apart from maintenance of the systems or training of the residents on their use, projects whose operation or their very nature relies heavily on the extensive use of engineering or other technologies risk becoming obsolete in a rapidly changing technological environment. In order to ensure their operation, they should be updated or upgraded. Moreover, in recent years we have had relatively cheap energy", notes Akis Tilemachou.

Nevertheless, it would be unfair to limit the imprint of the Solar Village to only those systems that did not work as planned. It is certainly interesting, perhaps the most interesting, that the Greek State made such a breakthrough. It was perceptive enough to imagine and approve, even by means of exception to the usual activity of the OEK, the construction of such a settlement at that time.

Moreover, over 30 years down the line, the Solar Village still remains a lively neighborhood. The buildings are correctly oriented and arranged in elegant blocks with sufficient public space, squares, and patios ─such a rarity for Greek cities. It is also likely to have contributed to the "liveliness" of the whole area. Walking towards the Solar Village, for many blocks most of the buildings seem to have been built at least after the mid-'80s, simultaneously to or later than the settlement itself.

Just like a muscle in the human body, a government agency, if left idle for too long it atrophies. After the closing down of the OEK in 2012 without providing for a successor scheme, the Greek State lost the ability to design and run similar projects. It can no longer implement a housing policy and, thus positively influence the development of cities, visualize a sustainable future and adapt accordingly.

-------

After a decade of no housing policy, pressing housing problems emerged. How can appropriate measures be designed from scratch, avoiding the mistakes of the past? Who will implement them, employing how many people, and from what background? How much money is needed and how can funding be secured, with a minimum fiscal impact? And, lastly, after the experience of the crisis and the bailouts, can the Greek State regain its ability to transcend its era, successfully this time on?

An important first step would be to ask these questions and engage in public debate. But what might the answers be like? At this point, it would be useful to have a look outside the country to the rest of Europe. Different countries have different ways of pursuing their housing policy, which were shaped under different circumstances. It is difficult ─and possibly doomed to fail─ to simply transfer the measures taken by one country to the context of another. However, different perspectives on housing reveal the problems that need to be addressed and the options available.

Rented social housing in Austria

In 1995, "starchitect" Jean Nouvel, who among other things designed the Paris Philharmonic and the extension of the National Museum of Art in Madrid, delivered his designs for the redesign of the first of the four Gasometer towers. Almost simultaneously, three other Austrian architects delivered similar designs for the other three towers. The Gasometers, four large, circular gasholder houses (each 70 meters high and 60 meters in diameter) near the center of Vienna, were built at the end of the 19th century. However, by the mid-1990s they had been deserted for more than 30 years.

Nouvel and the other architects contemplated the transformation of the gasholder houses into concert halls, shopping centers, cinemas, gyms, student residences, and dwellings. The project was finally completed six years later and basically transformed the entire area. Today, it is a vibrant neighborhood with more than 4,000 people moving about every day and using the location as their permanent residence. The area has now also gained tourist interest: guided tours are regularly held for those who want to learn more about the old gasholder houses and their restoration.

However, it is worth paying more attention to the dwellings inside the Gasometers. Of the 800 dwellings in total, around 600 are social housing. There are owned by the City of Vienna and the apartments are available for rent to beneficiaries of the relevant social housing programmes. Rented social housing is rather common in Austria. In Vienna, a city of 1.9 million inhabitants, the City and a number of non-profit cooperatives operate around 200,000 rented social housing properties. Across the country, 1 in 5 residences is a rented social housing property, and Austria is one of only six OECD countries, where, between 2010 and 2018, the proportion of rented social housing in proportion to the total increased. Eligibility criteria for rented social housing beneficiaries are particularly generous: they have been estimated to include the vast majority, around 80%, of households in the country.

"The social housing system in Austria began with industrialization", explains the Austrian ambassador in Athens, Hermine Poppeller. In some regions, such as Styria, this development was linked to a large extent to the industry because there was a great need for workers in the mines. On the other hand, Vienna, as the seat of the House of Habsburg in the early 19th century, was a very attractive city for people to live and work in. This gave rise to a significant need for accommodation. The City of Vienna then decided to start a system of social housing and the first cooperatives were established.

But how does such an old system that depends so much on State intervention actually work? How is it organized? "Each city has set its own eligibility criteria for beneficiaries", explains Hermine Poppeller. "The hundreds of non-profit housing cooperatives are funded through special loans from housing banks. They also collect contributions from municipalities and, of course, the rents paid by the beneficiaries. This builds up a capital which they then use to manage dwellings and make the necessary investments in infrastructure".

Although Austria subsidizes a certain number of loans or, more rarely, provides financing for very poor households to purchase a house, the Austrian housing policy is based on rented social housing. It is hardly surprising that rents, which are mainly determined on the basis of the area and the construction costs, are significantly below market. This is a parallel real estate market. Does this affect prices on the free market? "Certainly, there is a link between the State-subsidised housing market and the free market", says Hermine Poppeller. "This is of course not true in all cases. For example, luxury house prices follow the international luxury house market without being affected by what happens in social housing".

Several combined interventions in France

France is also a country with a developed rented social housing system: about 14% of all dwellings in the country are operated in this way. However, the system is funded differently from the Austrian one. "There is a dedicated mechanism; 1% of wages allocated to housing", says Arthur Acolin, French urban planner, Associate Professor in the Department of Real Estate, University of Washington. "The social housing contribution has now been reduced to 0.45%, but its name has not changed. This rate is deducted from all wages paid in the country by businesses above a certain size and is used to provide funds for rented social housing. A smaller proportion is used to support home ownership. Businesses also have a say in how this money is allocated and sometimes ask for extra benefits for employees in their sector".

Also, this system was introduced later than the Austrian one. Almost simultaneously with the post-war reconstruction, the French moved en masse from the countryside to the cities, thus creating new housing needs. To meet these new needs, in the 1950s and 1960s the authorities built huge social housing blocks with hundreds of apartments each, in the suburbs of French cities. Many of these complexes turned into ghettos. "Although more recent investments have been made in re-development, in many of these early blocks today there is poverty and crime", explains Arthur Acolin.

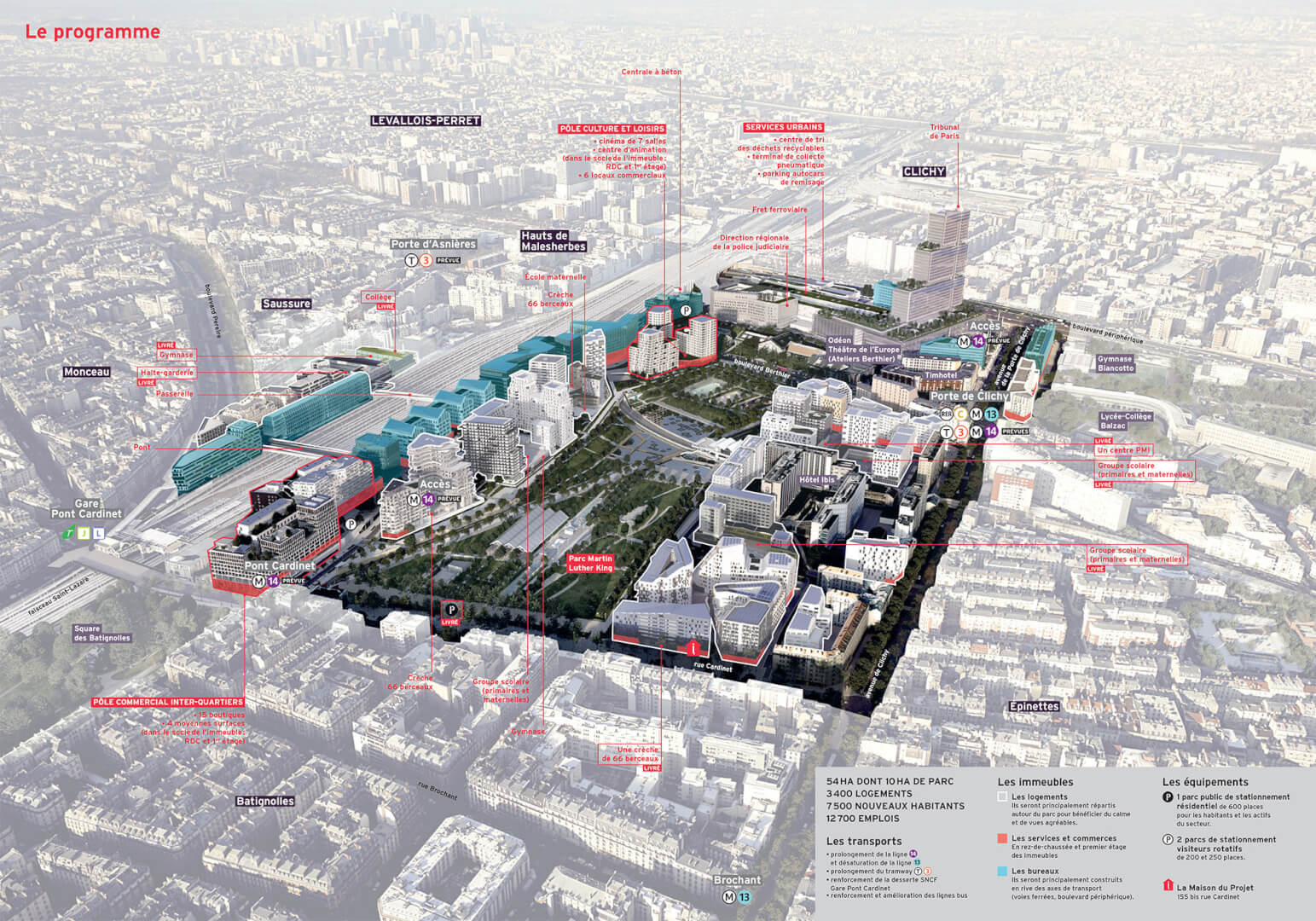

However, that is only part of the story. Of the approximately 5 million social housing units in operation in France, as much as 2 million have been added in the last 20 years. "These are usually smaller complexes of 10, 20 or 30 apartments, scattered in urban areas, even in more expensive areas in the center of Paris. A great effort is now being made to carry out smaller projects that are better integrated in each area where they are developed. In addition, even the larger new projects include dwellings that are available both on the free market and on the State-subsidised market", says Arthur Acolin, referring to a project currently underway in the Clichy-Batignolles district of Paris.

In an old train depot located in the 17th arrondissement of Paris, spreading over an area of 54 hectares, a 160-meter-high skyscraper designed by Renzo Piano was built and now accommodates the new Courts of Justice. Across the street from the courts, around a large 10-hectare park where three state theatres, offices, schools, and shops are located, 3,400 dwellings are under construction, half of which are rented, or planned to be rented as social housing. Many different eligibility criteria apply depending on the area, and for such a new apartment in an attractive location, it could take longer than five years for the beneficiaries to move into their new home.

Social housing accommodation in popular areas has a negative side too. It also brought a strange kind of delinquency: "There were reports in the French Press of beneficiaries subletting their homes via Airbnb. Of course, they had to pay a fine. As a result of these incidents, the municipalities stepped up restrictions", says Arthur Acolin.

Apart from rental housing, the French government also allocates a fairly substantial rent allowance, to which about half of the households living in rented accommodation are entitled, including beneficiaries of social housing. This allowance ranges from one-third to half of the rent.

To some extent all these measures, together with other factors, are likely to work: the proportion of tenants paying more than 40% of their income in rent is relatively small ─ 8% in cities, 3% in the countryside.

However, although the French system is self-financed to some extent ─due to the "1% of wages allocated to housing"─ it is also highly interfering and costly. Could it be otherwise? "There is no silver bullet", reckons Arthur Acolin. "Accommodation is expensive and properties are also expensive to maintain. If you want to live in a good location, the price of land is also expensive. So, you have to find ways to make that equation work out, which means committing significant resources. In the US, where I live and work, there's this theory that if you make the market work or find the right incentives, you don't have to spend that much. But in any case, when the household income is not sufficient to pay the cost of accommodation, you have to find some way to subsidize it. That way may be, more or less, indirect, but even that still costs".

The case of Spain: A different approach

Our conversation with Clara Martínez-Toledano, a Spanish Assistant Professor of Finance at Imperial College London, turned at some point to the rent allowance. "I have my doubts about the effectiveness of rent allowance", she argues. "As landlords are aware that tenants receive the allowance, sooner or later they are free to raise the rent by that amount. So, it is likely that the rent allowance, or part of it, will eventually be transferred to the landlord and not to the tenant who is basically the one in financial distress".

The rent allowance has been introduced relatively recently in Spain and, for the moment, it only applies to some low-income households and covers a small portion of the rent, especially in the cities. "At the end of the day, the measure did not apply to many people because there are all these restrictions", says Mariona Segú, Assistant Professor at the CY Cergy University in Paris, who has dealt at length with the housing issue. "In fact, this measure was funded by a specific budget, many people applied, but at some point the funds ran out and new funds had to be allocated".

Spain, like Greece, had put in place measures that encouraged people to own or build a house, rather than rent. "Buying a house is something like 'the Spanish dream'. Every Spaniard dreamed of owning a house", explains Mariona Segú. "There is a saying in Spanish that 'bricks never fall' meaning that investing in a house is always a safe investment. But it's not only a safe investment, it's also a profitable one. This culture was also encouraged by governments. Of course, this was before the crisis. Over the last decade, Spain suffered greatly from a real estate and mortgage bubble, which led to mass foreclosures once it burst".

Spaniards wanted to become homeowners, so governments made sure to help them. The Spanish State's housing policy was also ownership oriented. It mainly provided subsidies for mortgages and built houses which it later offered to beneficiaries. Today, 3 out of 4 Spaniards are homeowners, a rate similar to that of Greece (73%) and considerably higher than that in Austria (54%) and France (65%). Similarly, rented social housing is relatively non-existent (less than 2% of all dwellings).

"A problem emerged because social housing units were for sale and not for rent until quite recently", says Mariona Segú. "Essentially, this enabled some people to buy a house at a low price as beneficiaries, and after 30 years they or their children could sell the house at market value and make a big profit. This basically is advantageous for the beneficiaries, but in this way, the State gradually loses all its social housing stock and is forced to keep on building new dwellings".

In 2021, Spain included in its Recovery Fund plan a project to construct 20,000 energy-efficient social housing units to be rented out as social housing. These are basically properties owned by Sareb, the State-owned 'bad bank' which has held thousands of properties that were foreclosed over the past decade. However, Mariona Segú has her doubts: "It is very likely that these houses are located in areas where people do not want to live. It's a recurrent theme in the public discourse, that there are three million vacant houses in Spain. Yes, this is true, but these houses may not be in the big cities or their suburbs. There might be a mismatch with the actual needs. I would be surprised if, out of the 20,000 'bad bank' dwellings, half of them were in areas with some demand. Even if they were, 20,000 dwellings by Spanish standards is too small a number to make any noticeable difference".

The housing issue is consistently high on the Spanish public agenda. However, even after the increases of recent years, Spaniards, on average, do not pay as much as, say, Greeks for accommodation: they pay 11% of their income (compared to 34%) in the cities. But the youngest and poorest face a disproportionate problem, especially in areas where, for various reasons, prices are rising too rapidly. This situation has put considerable pressure on short-term rental platforms, as it has coincided with their expansion.

Mariona Segú participated in a research team that attempted to measure the impact of Airbnb's entry into Barcelona back in 2015. This study actually found a statistically significant increase in rents after the launch of the Airbnb platform. This increase was threefold in highly touristic areas, i.e., those with many listings on the platform. "It seems that prices did increase due to Airbnb, but not unrealistically. From a researcher's perspective, one can say that there has been an increase, but one cannot fairly say that Airbnb is to blame for the full increase in rents in the given period. Some have used our research to argue that the effect is not that large and that we shouldn't worry too much. Others said 'there is something here, we need to take some action'", adds Mariona Segú.

However, the debate on the impact of the platforms is still ongoing, and experts have not come to a conclusion yet. At the same time, many cities do not afford the time to wait for such a conclusion ─the big rise in rents has led them to impose restrictions in tourist areas. In September 2020, the Catalan local government-imposed restrictions on the amount of rent that landlords can charge their tenants in some tourist areas of the region, including the Barcelona city center. The restriction remained in force for only a year and a half, until March last year, when it was overturned by the Spanish Constitutional Court.

The relatively short duration of the restrictions, as well as the fact that there was reliable data on rental amounts and new rentals (it is obligatory to declare them on an online platform) triggered yet another round of research. As a writer of one of those studies, Mariona Segú explains: "We found a significant decrease of 5-6% in rents in the areas where restrictions were imposed. But we did not find a reduction in the number of new leases after the measures were introduced. So, there was no impact on supply, landlords appear to have continued renting their properties at the same rate, at slightly lower prices. However, what we observed is probably a short-term impact. One might assume, that the impact on supply is not seen in the first year but will be felt later".

------

As demonstrated by the stories of other countries, there is a common ground for many of the problems, at least in Europe. The pronounced investment interest in real estate in city centers, a decade of declining, stagnant or weak income growth after the 2008 global crisis, coupled with new options for homeowners to make use of their properties, such as Airbnb, have given rise to new problems everywhere. There is also an increasingly urgent need for renovations and energy upgrades. In Greece, it seems that the same challenges are more acute than anywhere else in Europe.

An Odyssey in Athens

"The conclusion I drew from my house-hunting experience in Athens is that if we, as a couple, want to move to the city center at some point we both need a second job urgently", says Lina Giannarou. The journalist in the "Kathimerini" newspaper recently recorded her apartment-hunting safari (or "Odyssey") in the center of Athens. She describes her experience in considerable detail. Available houses had serious defects, were poorly maintained, or even unfit for habitation with landlords demanding disproportionately high rents. She was so astonished that, as she says today, she wondered "if it was really worth it to be in financial distress so that you can be near theaters, bars and restaurants that you won't have time to visit anyway".

But it was not only the apartments and prices that made a lasting impression on her, but the attitudes too. "Real estate agents really made very little effort to 'sell' me a house", she recalls. "I made dozens of appointments, and not a single real estate agent made a follow-up -phone call to ask if I was truly interested, to add any information, or maybe suggest another apartment. To this day, I haven't figured out if their lack of interest was down to the fact that there were so many people interested or because they had realized that at these prices it would be hard to get a deal anyway".

An ugly picture

All available evidence points to the fact that this was not just a single person's bad luck. Official Bank of Greece data clearly show the increase: in 2022, it seems that the apartment price index is set to close with an increase of more than 10%, compared to 2021 (restrictions: temporary data, fourth quarter pending). For new, five-year-old apartments in Athens, the increase could exceed 13%. In 2021 too, the increase compared to 2020 was smaller, yet significant: about 7.5% throughout the country.

The "spitogatos" website, which contains mass property listings for sale and rent, publishes detailed price data per region. These are not official figures, yet likely to be indicative. In 48 of the 62 regions for which data is published (roughly identical to the country's administrative Regional Units) there was an increase in rents in the last quarter of 2022, compared to the same time in 2021. In fourteen of these, the increase was over 10%. In Arcadia, Kilkis, Lasithi, and Messinia, the increase in rents, as reflected in the ads of spitogatos, exceeds 20%. Of these four regions, only the region of Kilkis (in Northeastern Greece) offers rents below EUR 5.00 per square meter.

On the other hand, it is difficult for incomes and especially for wages to grow at the same rate. Moreover, the crisis of the previous decade is still being felt by the Greeks. "Coming out of the crisis, the housing and real estate market became an object of interest for foreign investors. This drove up market prices and rents", says Thomas Maloutas. "But incomes did not follow up this trend, so the gap widened even more. This has created acute problems when it comes to housing".

However, it is important to keep in mind the high rate of home ownership, around 73% of the population. Also, on average, real estate property accounts for 70% of a household's assets. Therefore, the vast majority of homeowners, almost 3 out of 4, have seen their property value increase in recent years, without usually facing the psychological burden of looking for accommodation. 63% of homeowners are staying in their owner-occupied homes.

But what about the rest, that 27% who are not homeowners and those who do not live in the property they own? Things are really tough there. According to Eurostat data, Greek households spend around 37% of their household income on accommodation ─the highest percentage among EU countries. Around 1 in 3 households living in cities spend even more, actually more than 40% of their income, on accommodation─ also the highest percentage in Europe. The problem is even bigger for the poorest households. According to the OECD, the poorest 20% of Greek households pay 43% (median) of their income on rent. According to a poll by the Eteron Institute, 3 out of 4 tenants aged 18 to 44 say that they experience stress or anxiety as a direct result of the rent they have to pay.

Apart from the immediate problem of accommodation for a considerable part of the population, this situation has created more, less obvious problems, such as inequities. Homeowners are seeing their property gain value, while tenants find it increasingly stressful to find and keep an accommodation. It is also likely that the increase in rents will disproportionately affect young people and thus further aggravate the country's demographic problem. On average, Greeks leave their parental home after the age of 29, later than the average European (at 26.5). The proportion of young people aged 25 to 34 who are owner-occupiers has fallen by about half in 13 years, from 2005 to 2018. According to the above-mentioned Eteron poll, 1 in 10 tenants said that rent increases is forcing them to put off starting a family or having children.

Potential solutions

The crisis seems to be quite deep and will not be easily tackled. Are there any measures that could make a difference? After the closing down of the OEK in 2012 and the elimination of the contributions that sustained it, the housing policy in Greece has come to naught. The lack of a housing policy is likely to have contributed to the current difficult situation. But what might a modern housing policy look like? Where should policy designers need to look?

One obvious alternative to this problem is vacant buildings. According to the last census in 2011, 35% of all dwellings in Greece, 2.2 million in number, were empty ─600,000 of them in Attica only. If one takes out holiday homes or second homes, there are 900,000 houses left, 314,000 of them in Attica. More recent figures, obtained from the Independent Authority for Public Revenue (IAPR) and made public by the government, suggest a similar picture: 770,000 empty houses (as declared in the E2 form) throughout Greece. A better and more systematic inventory of these hundreds of thousands of properties could better evidence their potential: What is their condition? Where exactly are they? What is the demand for the areas in which they are located?

"Making better use of vacant properties is a key point in tackling housing problems", says Alexis Patelis, Chief Economic Advisor to the Prime Minister. "But it is also the best practice, given the constraints that the climate transition will place on the overall building stock. Greece, after all, has the highest number of dwellings per capita among OECD countries. Prices will be kept down when supply is triggered".

Another key point relates to imported demand and Airbnb-like platforms. In 2019, Airbnb had more than 125,000 listed properties across the country. Although the obligation to declare income from platforms has been in place since 2017 and, in some cases, there is a limit to the number of days that someone can make their property available on the platform, international experience shows that more can be done. "Short-term rental has entered too strongly into the Greek context", says Thomas Maloutas. "The supply in rented housing has been reduced and this has added to rent price increase. Based on the international experience, there are many things that can be done. However, there is a positive side too ─for example, many buildings have been upgraded in this way". Similar restrictions on "golden visas", such as the recent doubling of the threshold from EUR 250,000 to 500,000 for some areas, are likely to mitigate somewhat the demand from abroad and thus have some impact on rent prices. But here too, other countries are taking much more drastic measures: Portugal has recently abolished the golden visa.

Last September, the government announced an ambitious EUR 1.8 billion package of housing measures, which it claims will benefit 137,000 beneficiaries. This includes subsidies of housing loan interest rates in young people, renovation and energy upgrade subsidy schemes for vacant houses and young people, an increase in student accommodation allowances, and even a "social antiparochi" scheme, where the State will transform vacant buildings into residential properties and let them out to beneficiaries at low rent. Many, perhaps most, of these schemes and measures go beyond the current government's mandate and therefore the details of their implementation and their impact remain to be seen. Other political parties have also put forward their proposals to address the housing problem, focusing both on restrictions on platforms and on the reintroduction of social housing.

The dialogue on housing policy in Greece has reopened. Past experience and the experience of other countries have valuable lessons to offer. How can a new, self-financed, and sustainable housing policy model be developed from scratch? How will it address the new challenges brought about by more modern ways of exploiting real estate? How will it finally mitigate inequalities before they get out of hand without standing in the way of the real estate market growth? These are the questions that will have to be answered in the near future.

Original publication date: April 2023