In the last forty years, the problem of obesity on our planet has tripled in size. In 2016, 1.9 billion adults worldwide were overweight and of these, 650 million were obese. This phenomenon is particularly acute in Greece -our country ranks first in the EU in childhood obesity, and also holds one of the top positions in adult obesity. 63% of Greeks over the age of 18 are overweight or obese. What are the consequences of this phenomenon for our health, society, and the economy? What are its causes? And what could be some possible solutions? diaNEOsis commissioned a research team, coordinated by Professor Giannis Manios from Harokopio University, to prepare a study that maps the problem to its true dimensions, and proposes a series of actions in schools and in the primary health care structure in order to address it.

You can read the whole study here (in Greek) and a brief description here (in Greek). We briefly list some of the key points below.

1. What is obesity?

Obesity is defined as the increased accumulation of body fat within the human body, that can adversely affect health. It was recognized as a disease about half a century ago and is now one of the most important chronic health problems in the world. Obesity is essentially a result of the body's positive energy balance. Every day each and every one of us adds energy to our body by consuming food. At the same time, we consume energy through physical exercise, activities, and by maintaining the vital functions of the body -just by staying alive. If the energy we acquire is greater than what we consume, this extra energy is stored in the body as fat. If this is done systematically, fat accumulates, and our body weight increases. Individuals who have accumulated more than a certain amount of fat in their bodies are considered overweight. Individuals who have accumulated even more, by crossing a higher threshold, are considered obese. Although the issue is commonly referred to as "obesity", many of the problems and conditions listed below generally affect people who have more body fat than normal -and therefore that usually also includes overweight individuals.

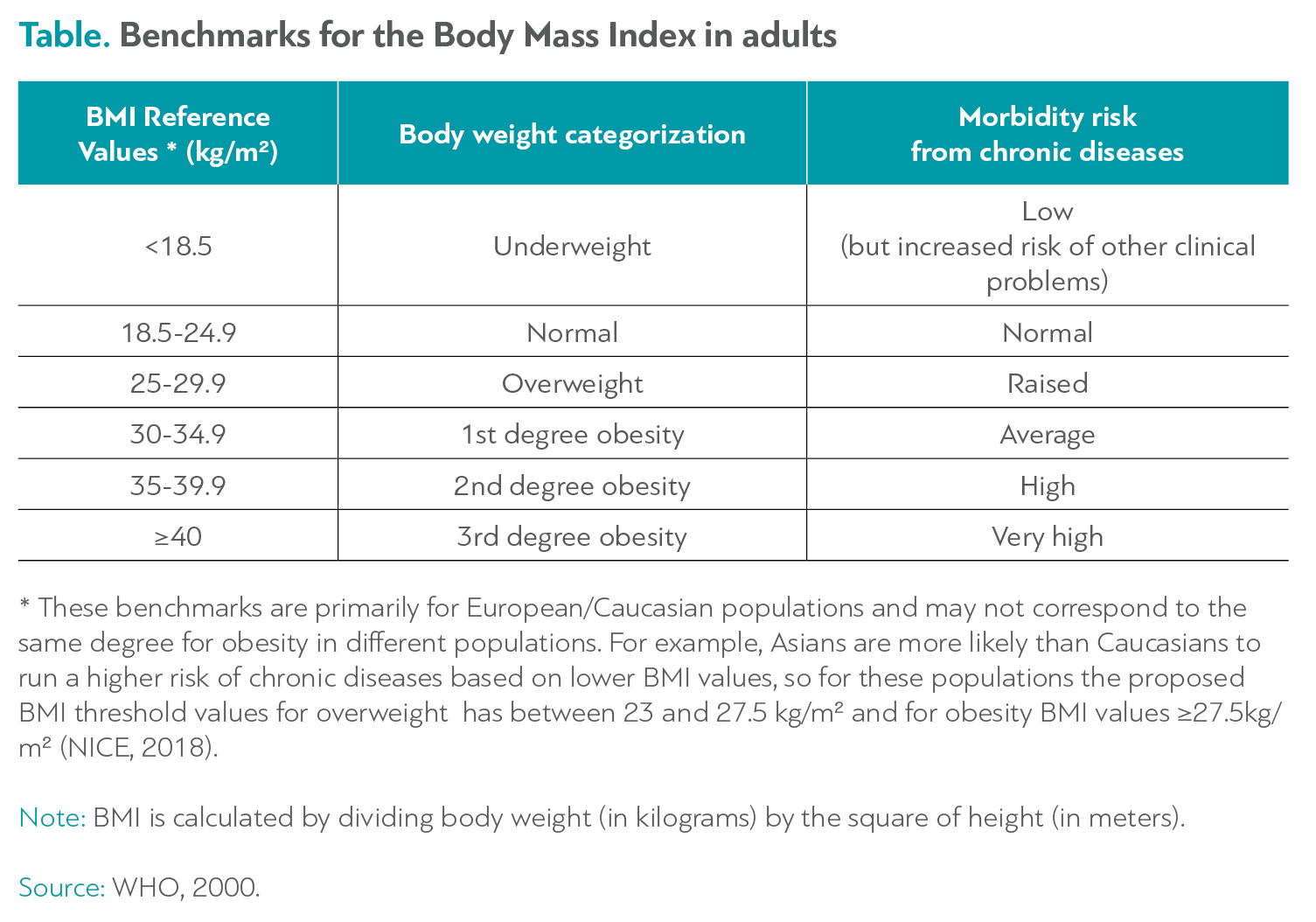

Whether a person is obese, overweight, or not is measured by calculating their body fat. However, because this is a complex process that requires specialized equipment, the "Body Mass Index" is usually used (known by the acronym "BMI"), and it measures body weight in relation to height, thus indirectly estimating the accumulation of fat in the body. The BMI is calculated by dividing body weight in kilograms by height squared, in meters. For example, a person 1.75 meters tall and weighing 70 kg has a BMI of 22.9. As can be seen in the table below, based mainly on European/Caucasian adults, individuals with a BMI over 25 are considered overweight and individuals with a BMI over 30 are considered obese (for individuals of other ethnicities the benchmarks are slightly different). You can calculate your BMI now, and see which category you fall into.

Different benchmarks are used to measure obesity in minors, which also take into account age and gender. You can find them in detail in Appendix 1.1 of the study (p. 190). It is worth mentioning that, in addition to BMI, other measurements are being used to assess obesity, such as waist circumference. Large values in such measurements may indicate an increased risk of developing chronic diseases even for individuals who do not have a high BMI.

2. Why is obesity a problem?

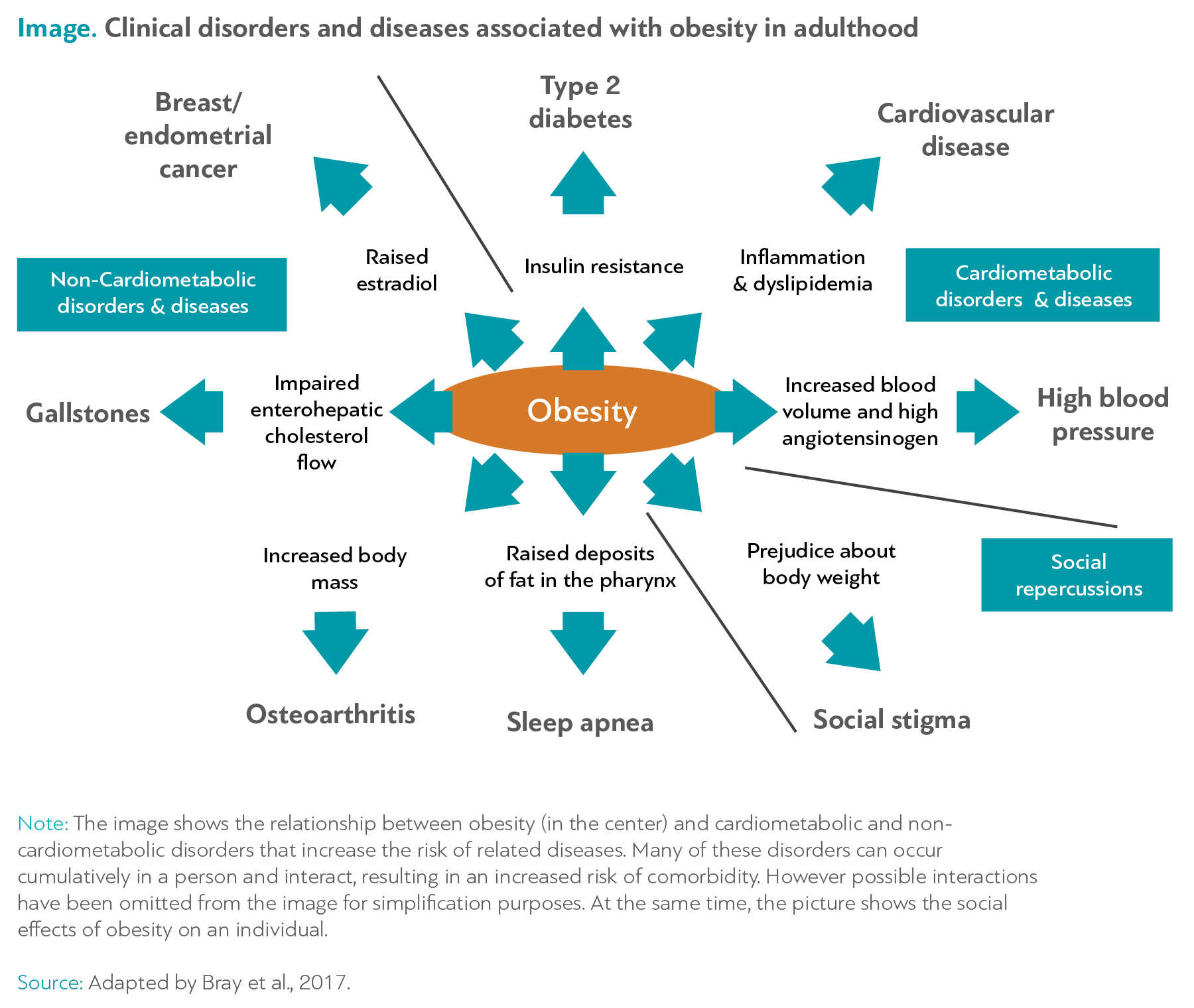

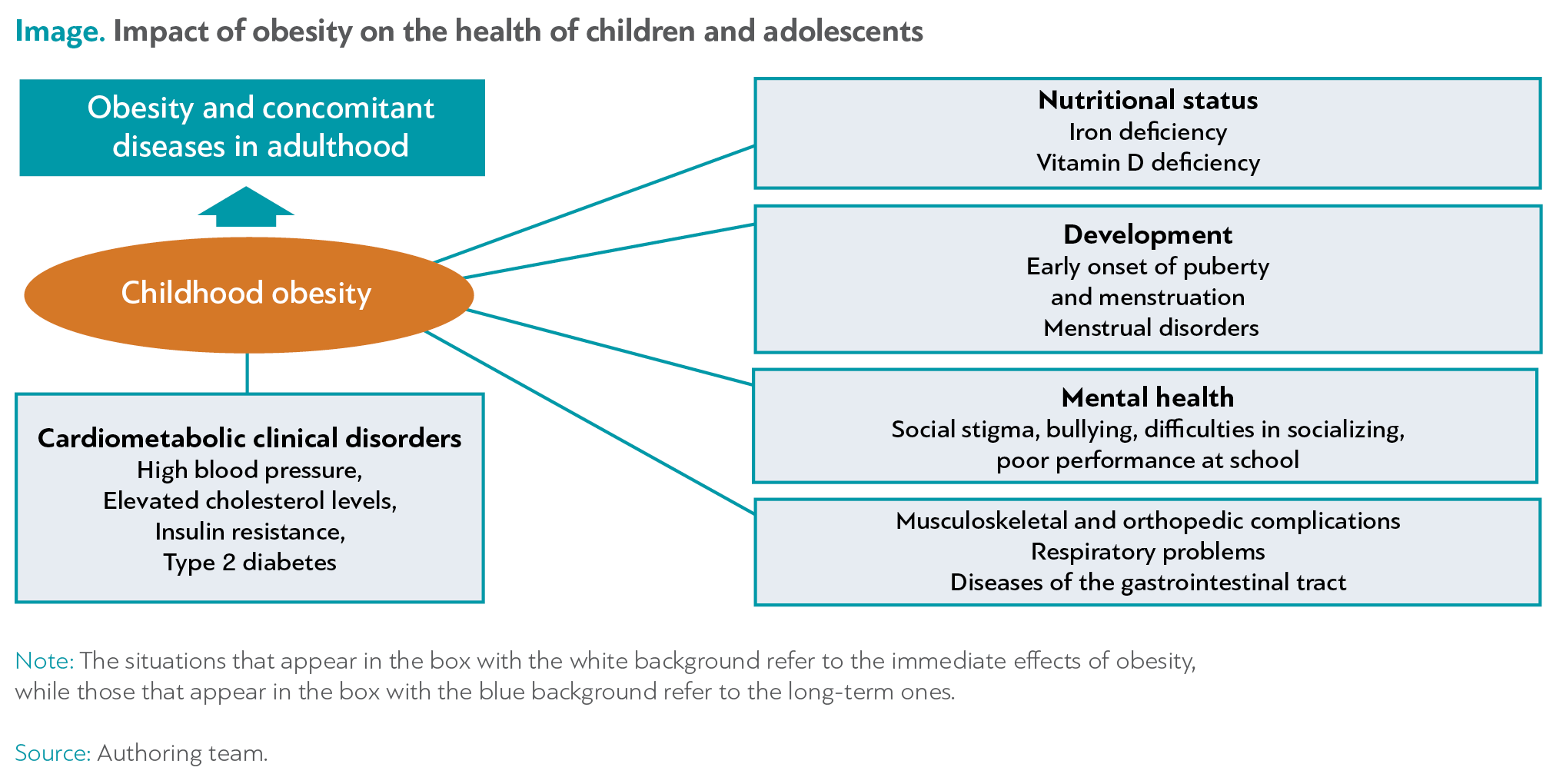

Obesity is associated with a number of heart and metabolic disorders, which can evolve into chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes (SD2 - 80-85% of SD2 in humans is attributed to obesity), cardiovascular diseases, some cancers, or osteoarthritis, gallstones and severe sleep disorders. Each 5-point increase in BMI, raises the risk of coronary heart disease by 27% and the risk of a stroke by 18%. Obesity also has implications in our mental health, as well as social implications, and financial costs (especially for the health system). In children, it is associated with iron and vitamin D deficiency, which can adversely affect their cognitive, muoskeletal, and physical development. And, of course, obese children are more likely to become obese adults.

But why does the accumulation of fat in the body cause such serious conditions? The cause lies in the fat itself and in the increase in the size of the fat cells within the body. It is worth explaining briefly what this means. In our body, we have adipose tissue, a loose connective tissue that is made up of fat cells and is extremely important for the correct functioning of the body. This is where the body's energy is stored in the form of fat and, on top of that, the tissue helps in the mechanical support and protection of our bones and organs, as well as in the thermal insulation of the body. When the amount of fat in the body increases significantly, it causes persistent, low-intensity inflammation. Moreover, the normal secretion of a number of substances secreted by fat cells also rises, and in high concentrations, this can cause damage to the arteries, the heart, liver, muscles, and pancreas. This in turn can disrupt, for example, the regulation of sugar in the blood level (that is, the efficient functioning of insulin, which is secreted by the pancreas). At the same time, the increased body mass causes an increase in the blood volume as well as systematically higher blood pressure. Consider that overweight individuals are 52% more likely to develop hypertension while obese individuals are almost 100% more likely to develop it than normal-weight people.

The increase in fat also triggers a number of other biochemical processes, such as the increase in the level of certain hormones, the disruption of the transportation of cholesterol from the liver to the intestine (a disorder that can cause gallstones) as well as a number of other issues, ranging from the accumulation of fat in the pharynx that can cause respiratory problems during sleep, to pressure on the musculoskeletal system and joints. Adipocytes, on the other hand, bind vitamin D, which is fat-soluble. Obese people, because they have increased body fat, often have a lower concentration of vitamin D in their blood. Among other effects, research has shown that people with vitamin D deficiency are more prone to become seriously ill or die if they contract Covid-19.

In children, in addition to the possible effects of obesity on their health before adulthood (ranging from increased chances of respiratory or orthopedic problems to menstrual disorders), there is also an increased probability of them developing conditions that usually occur in adulthood (diabetes, hypertension -about half of school-age children with obesity have particularly high blood pressure levels). Also, overweight children appear to perform less well in lower school and are more likely to be absent from classes for longer periods of time. And, of course, 70-80% of those teens remain obese as adults.

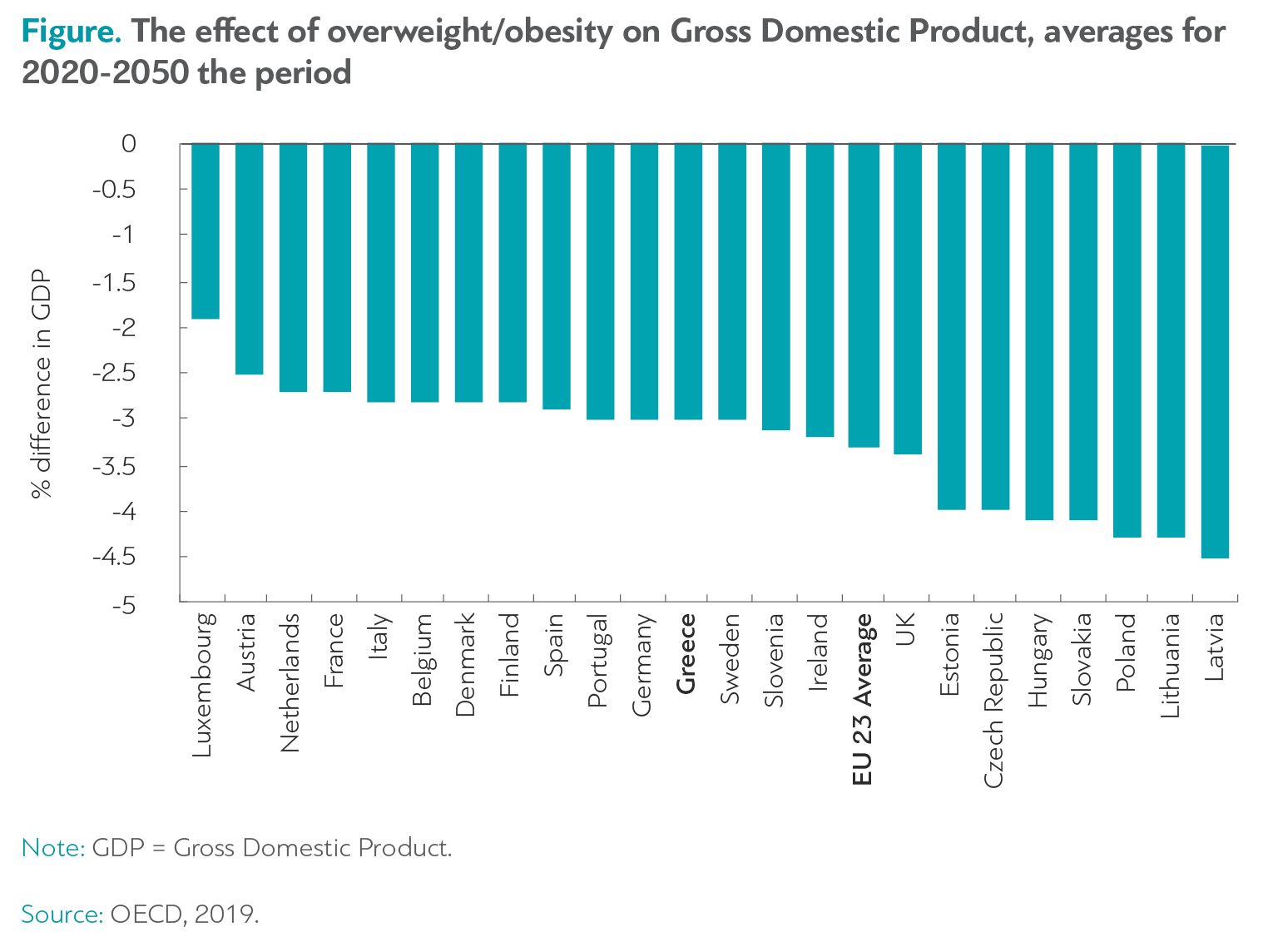

We can also not ignore the social and economic consequences of obesity. Prejudice often leads to social stigma and discrimination against obese people which, as studies have shown, contribute to the onset of anxiety and depression. According to OECD data from 2019, obesity is responsible for 9% of annual health expenditure in Greece. According to the same study, the annual GDP in Greece during the period 2020-2050 will be 3% lower than otherwise, due to the economic consequences of obesity.

3. How significant is the problem in Greece?

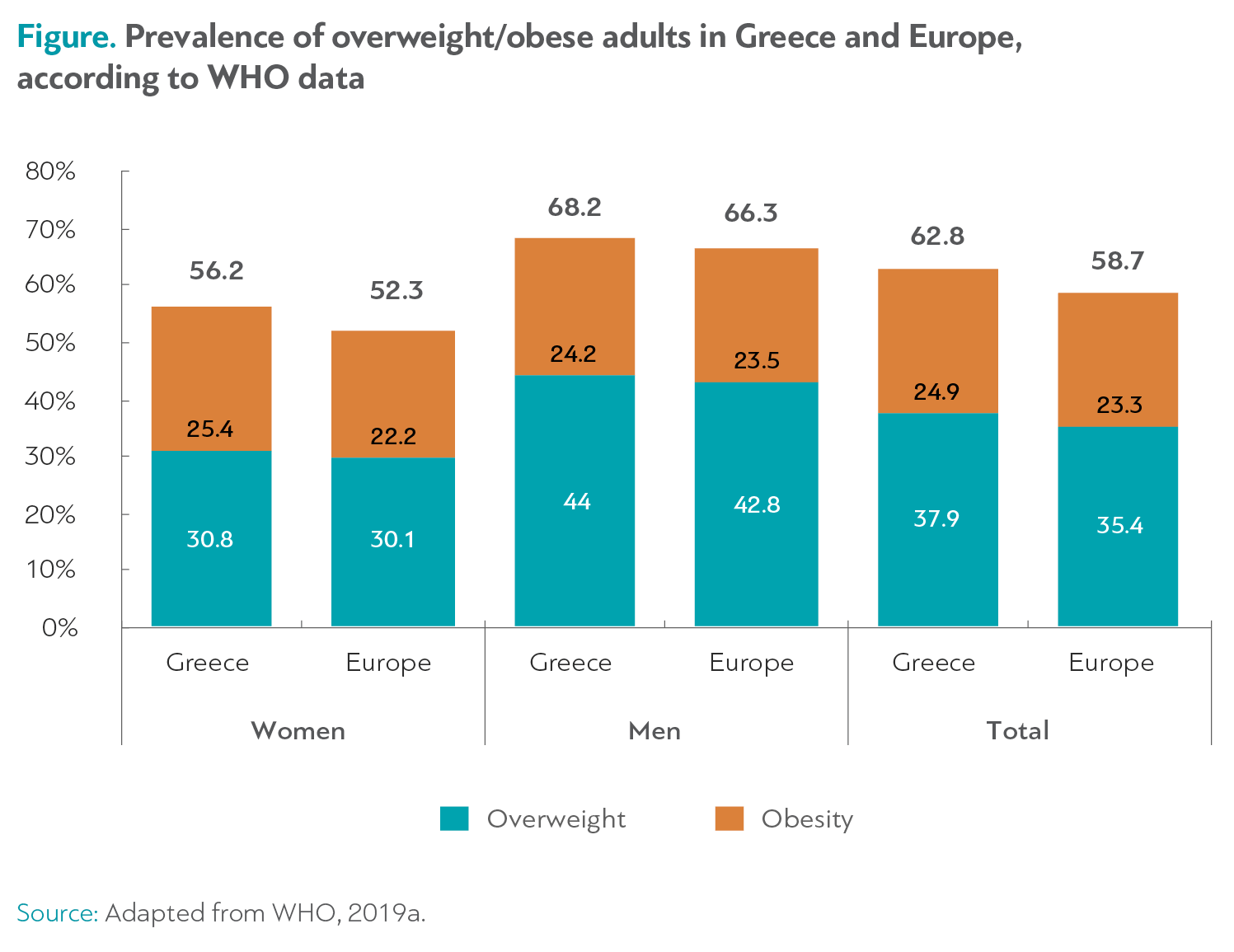

As we mentioned in the beginning, more than half of the adults in Greece are obese or overweight. According to WHO data from 2019, 37.9% of Greek adults are overweight and 24.9% are obese. 44% of Greek men and 30.8% of Greek women are overweight, while both sexes show the same rates of obesity: one in four Greek men and one in four Greek women belong to this category.

It is also interesting to note that in three-quarters of Greek families, at least one of the two parents is overweight or obese. In one in four, both parents are.

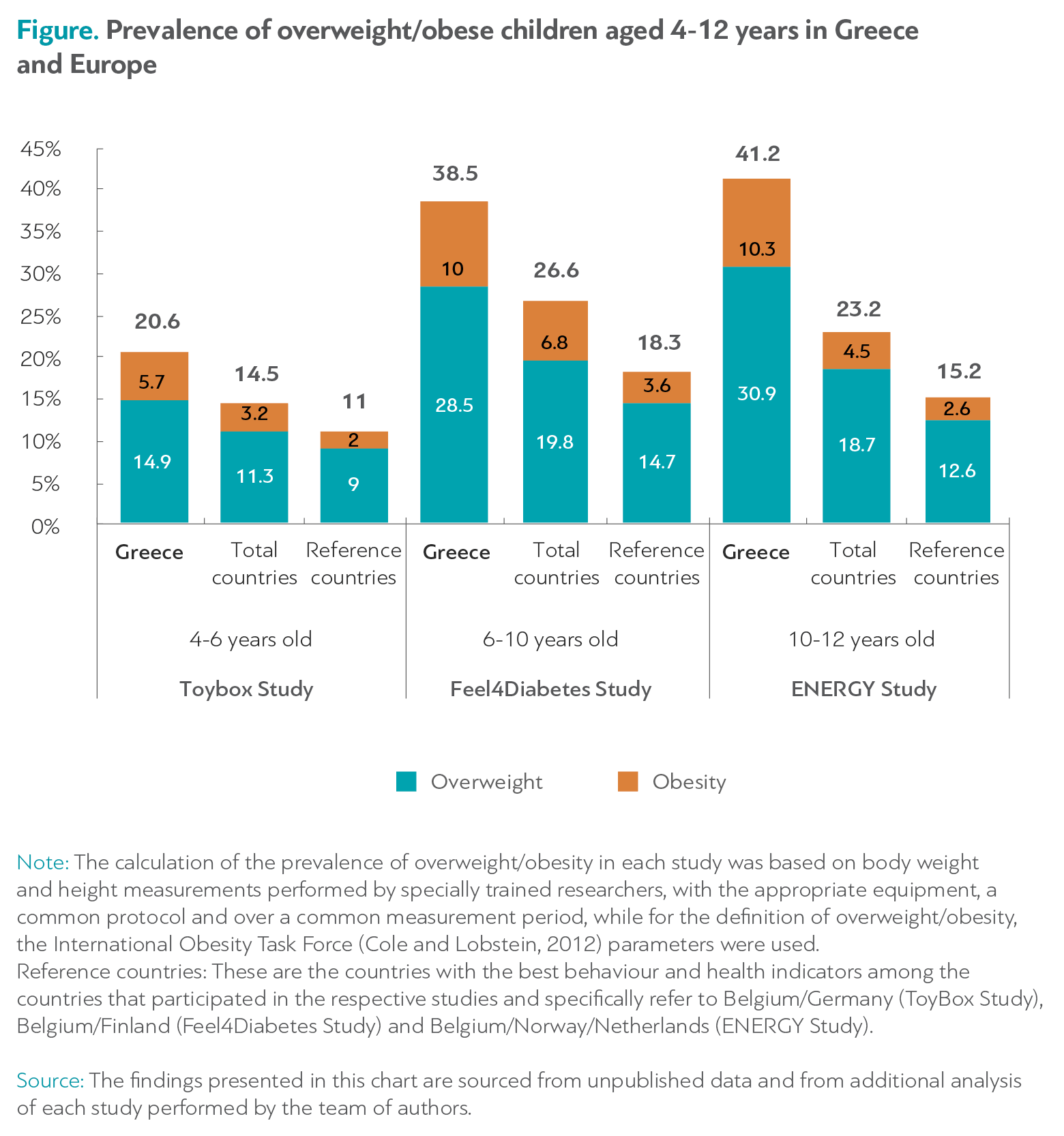

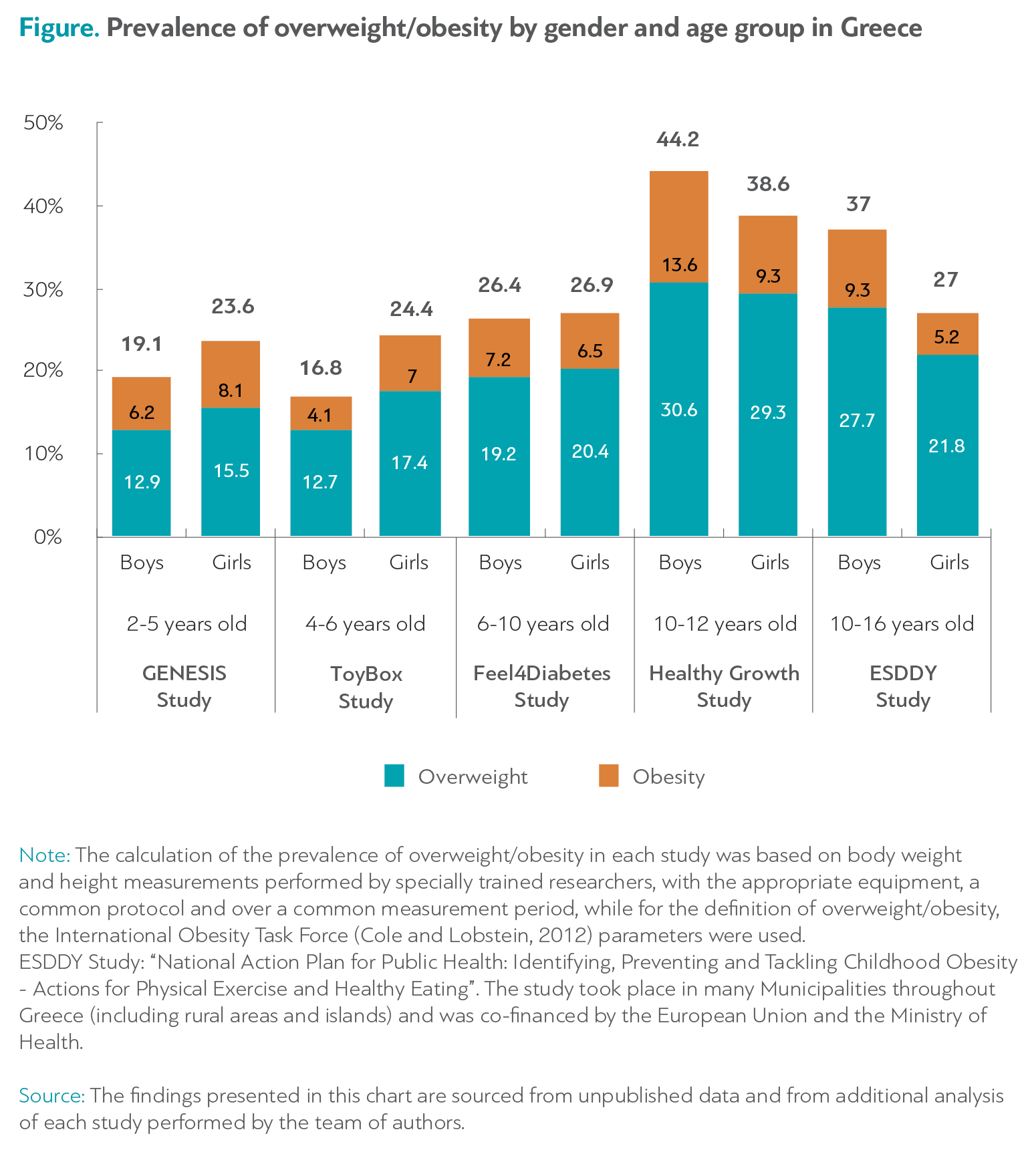

At the same time, children in Greece show the highest rates of obesity in Europe. The percentage of children aged 4-6 years who are obese or overweight is 20.6%. Among children aged 6-10 this rises to 38.5% and in the 10-12 age group it reaches 41.2%.

The rates of obesity in children seem to be higher in rural areas than in cities. Inequalities also occur within cities: only 2.7% of children in Chalandri (a well-to-do neighborhood of Athens) are obese -in Keratsini (a low-income neighborhood of Athens) the percentage is 20.3%. However, the rate of overweight children is similar almost everywhere -about one in three children in most parts of Greece are overweight.

4. What are the causes of obesity in our society?

As we mentioned in the beginning, obesity occurs due to the body's excess energy balance -that is, the intake of more energy into the body than we actually consume, with the excess accumulating as fat. However, there are various social, environmental as well as genetic factors that can increase the risk of developing this imbalance. Some of them can even appear in very early stages of life -even before birth. Before we look at these factors in detail, it is worth emphasizing that they act in a complementary fashion. The issue of obesity is complex and socially sensitive and often the attribution of responsibility at the level of personal choices or blame at the level of the family is simplistic and unfair. For example, you can read below, that the probability of a child being obese increases if their mother was smoking during pregnancy, or if the child gained weight too quickly after birth. Moreover, children who are cared for primarily by their grandparents are more likely to become overweight or obese than those who are cared for primarily by their parents. Or that 3 out of 4 Greek adults eat fewer fruits and vegetables than recommended. None of these factors are unique and do not lend themselves to easy blame. On the contrary, they function only in conjunction with each other and with the other conditions that define the life and the environment of modern society. In fact, some of the most crucial factors are not well known and rarely mentioned in public discussions relating to obesity. Such are neighborhood safety, how many houses have a yard, quality of sidewalks, easy access to sports facilities, or the financial circumstances of a family. Here below we list some of the most important factors influencing the phenomenon, which are analyzed in the study.

The best-known factors, of course, have to do with the lifestyle of children and adults. How much and what kind of food we eat, whether we exercise or are physically active, and how much time we spend on "sedentary" activities dramatically affect the likelihood of gaining weight, regardless of other factors. Recommendations for a proper energy intake for adults can be found in Table 5 (p. 117 of the study). These are things that seem "common sense" but, as it turns out, they are not. According to one of the surveys that gathered much of the data presented in this study, only 8% of Greeks know the recommendations for proper nutrition, and only 35.2% know the recommendations for physical activity (numbers that are significantly lower than in other European countries).

As already mentioned, in Greece, only 25% of adults consume the recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. This percentage may be small, but a number of studies show that the eating habits of Greeks are not much worse than the habits of other people with much lower rates of obesity. The crucial difference may be this: 68% of Greek adults do not exercise at all and do not engage in any sport –this is the largest percentage in the European Union. Greeks, on the other hand, spend more than three hours of their non-working time in front of screens -more than the residents of 15 other European countries. And, of course, there are other significant aggravating factors, ranging from the social environment and the neighborhood in which one lives to their financial situation, their available free time, and the amount of sleep they get. Some of these factors may also explain why Greeks do not exercise enough: in a recent survey, the percentage of Greeks who said they did not exercise because their neighborhood "does not have the proper infrastructure", "does not look attractive" or "is not safe" was twice the percentage of respondents in other European countries.

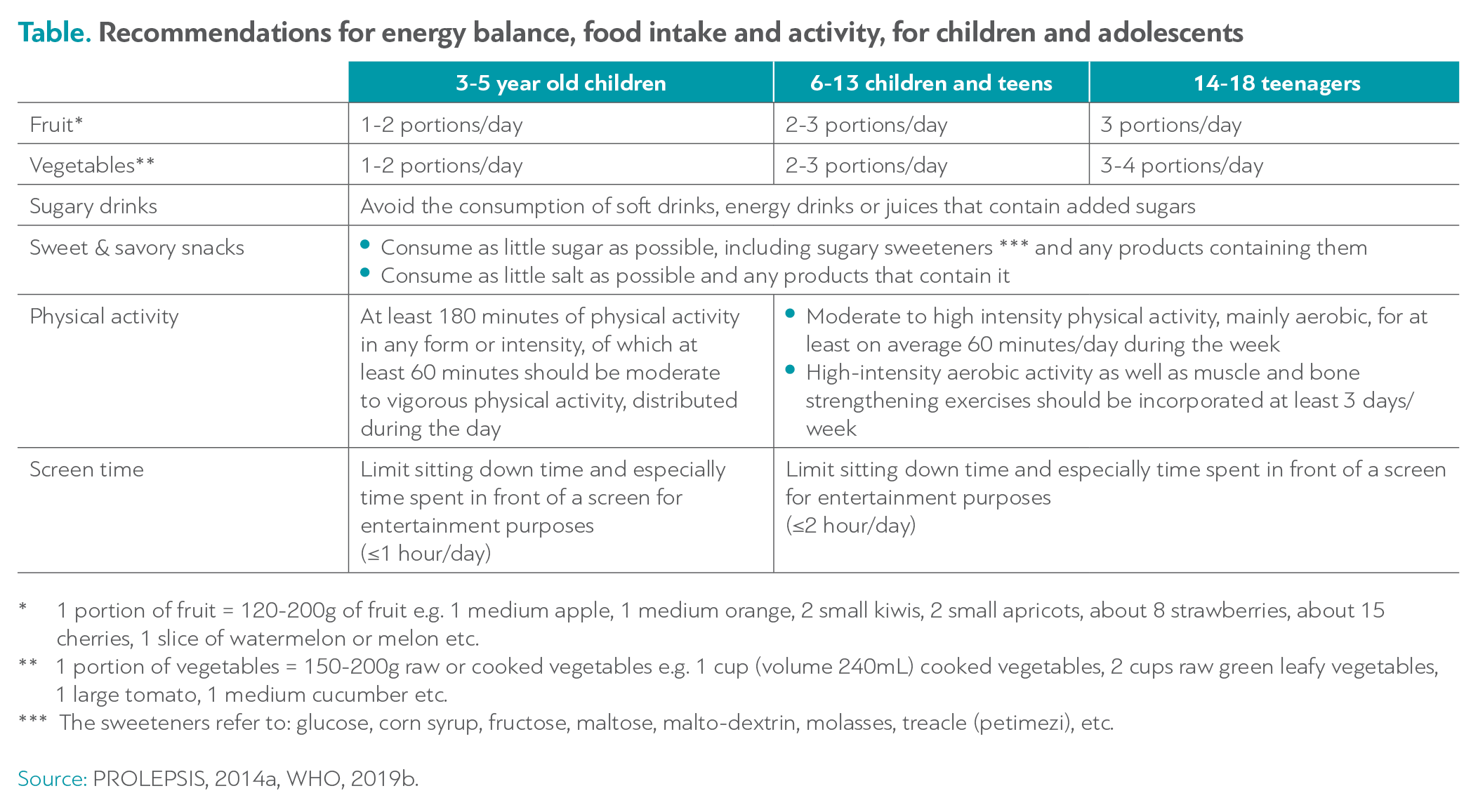

But what about the children? The following table provides the recommendations for nutrition and activity for children of different ages groups.

It seems that only a small percentage of families in Greece follow these recommendations. It has been established from all relevant research that a lifestyle comprising a higher consumption of energy-dense and high-fat foods (sweets, sugary drinks, snacks), lower fruit consumption, lower levels of physical activity, shorter sleep periods, and time spent in sedentary activities (TV and other screens) is more common among obese children -which, of course, is the case in other countries as well. In addition, the social environment of a child plays a very significant role. Parental educational level, the type of food available at home, influences from the educational environment and from peers (especially in adolescence), exposure to advertisements through the media, access to sports facilities or sports equipment, proximity to playgrounds and sports grounds, the type of grocery stores in the neighborhood but also the role of other people who contribute to the care of children (grandparents) are all extremely important factors. As mentioned above, according to a 2010 study (Moschonis et al., 2011) children cared for primarily by grandparents are 53% more likely to become overweight or obese than those cared for primarily by their parents. And, of course, there are more direct correlations. As one would expect, parental obesity increases the probability that children will also become obese. Interestingly, however, 22.3% of children with normal-weight parents are obese or overweight -a much higher rate than what is found in other countries in similar surveys (only 6.5% in Belgium & Finland, for example).

A serious but little-known issue is the underestimation of children's weight by their own parents. 88% of parents of preschool children who are overweight and 55.8% of parents of children who are obese, believe that their child has a normal body weight. This of course is not only a Greek characteristic -it frequently comes up in other countries as well.

But these are not the only factors that contribute to whether a child will become overweight or obese. There are others, that act from much, much earlier on. As evidenced by many studies, factors such as maternal excess weight before pregnancy, maternal weight gain during pregnancy, and maternal smoking during pregnancy (active or passive) play a very significant role in the subsequent development of the child. A child is 2.6 times more likely to become obese when her mother is obese before pregnancy. 35% of Greek mothers gain too much weight during pregnancy -their children are twice as likely to be obese.

11.5% of Greek mothers also state that they did smoke during pregnancy. According to Feel4Diabetes research, children born to mothers who smoked during pregnancy are 2.6 more likely to become obese. This correlation is even documented for second-hand smoke (passive smokers). Once born, however, there are other factors that affect whether a child will become overweight or obese. Babies born with a higher than normal weight are 1.8 times more likely to become obese as children. About 10% of Greek mothers exclusively breastfeed for the first six months -children who are fed this way during this period are 2 times less likely to become obese than the rest. On top of that, children who gain weight too fast in the first two years of life -more than 1 in 3 children in Greece belong to this category- are four times more likely to become obese later on in life.

All of these "perinatal" factors work in combination. No single factor determines by itself what will happen to a child in the future, but together they create an environment in which the probability of a child becoming obese increases or decreases depending on what happens during pregnancy and the first months of life. An indicator has been developed that takes into account the impact of these factors, and it is described in detail in Chapter 2 of the study (p. 79).

As is the case with other factors, while the role of perinatal factors is important, it is not the only one. Therefore, attributing responsibility to mothers or parents (or grandparents) for each of these factors individually is both ineffective and unfair. All later stages in life, with adolescence and the period after reaching adulthood being the most crucial, also affect the phenomenon of obesity, in complex and complementary ways. It is worth keeping these points in mind:

- Obese children are five times more likely to become obese adults than children of normal body weight.

- 70% of obese teens are still obese after the age of 30.

But at the same time,

- 70% of obese adults were not obese as children.

5. What does the study suggest?

Given that the problem of obesity is due to so many complementary factors, many of which are related to the lifestyle and personal choices made by families facing different and sometimes very difficult situations and challenges, it would be very difficult to find a general and straight solution to this issue.

However, efforts have been made. Since the 1970s, various information and obesity prevention programs have been implemented in a number of countries around the world. These included information drives for children and parents and various forms of interventions in schools and in families, some of which have had measurable and significant results. A detailed presentation of such programs for children and adults (with names such as "Know Your Body", "CATCH", "ToyBox", "Feel4Diabetes", "Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study" and "North Karelia" -the last one, part of the famous Finnish policy experiments, exist in Part 3 of the study, along with an analysis that explains what makes for a successful program (p. 158).

The researchers, taking into account all that has preceded (with emphasis on the "ToyBox" and "Feel4Diabetes" programs designed and implemented by the same research team), came up with a proposal to implement an action plan based on two priorities: on the one hand, the design and the implementation of a school intervention program, to promote healthy eating and increased physical activity for children and their families; and on the other hand the planning and implementation of a simple process for the timely identification of families at high risk of obesity and its accompanying diseases. The conduits of the intervention would be the Primary Health Care centers throughout Greece.

The proposed action plan consists of recording the developmental and health indicators of children, adolescents, and their parents through the already established medical examination of children used to complete the Individual Student Health Card (ADYM). The well-known ADYM, which must be completed by pediatricians for all school-age children in the country, can be enriched with data on parents (anthropometric characteristics, eating and exercise habits, other risk factors for chronic diseases) thus creating a system for evaluating health indicators of the population. In this way, "high-risk" families can be identified (always, as the research emphasizes, through strict procedures for the protection of personal data). These families will be referred to the Primary Health Care Centres (TOMY, Municipal Clinics, Health Centres) for medical assessment and access to counseling services by specialists, as well as interventions, programs, and information tools. The proposed action plan will include procedures for evaluating and measuring its effectiveness. It is described in detail in Chapter 3.5.