In December 2019, diaNEOsis in collaboration with Marc conducted its almost-annual survey "What Greeks Believe". The results of that survey vividly reflected the fundamental perceptions and views of the population at the end of a turbulent decade. By the time those results were published, however, our reality had already begun to change dramatically. It was Sunday, March 8, 2020. Since then, nothing has remained the same.

As of this writing, Greeks have already spent more than 50 days in confinement. During this time the economic activity halted; lives turned upside-down; plans were cancelled. We experienced the strangest Easter holiday of our lives and the dramatic effects of the pandemic on the country's economy (and our pockets) have already started to show. Nevertheless, by staying home we managed to save our health system from collapse, save the lives of countless of our fellow citizens, and avoid an unprecedented tragedy similar to those that occur in too many countries around the world, even in our very own neighbourhood.

But what is happening today inside Greek homes? How do we coexist—together, but each in their own refuge—after more than a month in isolation? What does our experience look like, how often do we go out, how do we work, how many of us work, and how do we expect the phenomenon to evolve in the future? How have our feelings changed in the last few peculiar months?

How Greeks Live during the Pandemic - Results (in Greek) (PDF)

To find answers, diaNEOsis partnered with Metron Analysis to conduct a telephone survey to a nationwide sample of 1,250 citizens. The survey, rolling from April 8 to 15, 2020, included 22 questions that map out how we live and what we think during these times of crisis. In the results, which you can read in detail here (in Greek), you will not find evaluations of the government’s performance, or who the Greeks prefer to be prime minister. Other studies follow such topics. But you'll find some interesting facts, such as how many of us are afraid of the virus, or how many leave their home every day—and where they go. You will also find some surprises. For example, Greeks nowadays are more optimistic and proud than they have ever been in the recent difficult years.

Full survey results can be found in this PDF, as well as these .xls tables. The data is open and downloadable in .sav. These resources are currently available only in Greek.

Below we briefly look at the main results and key takeaways.

1.

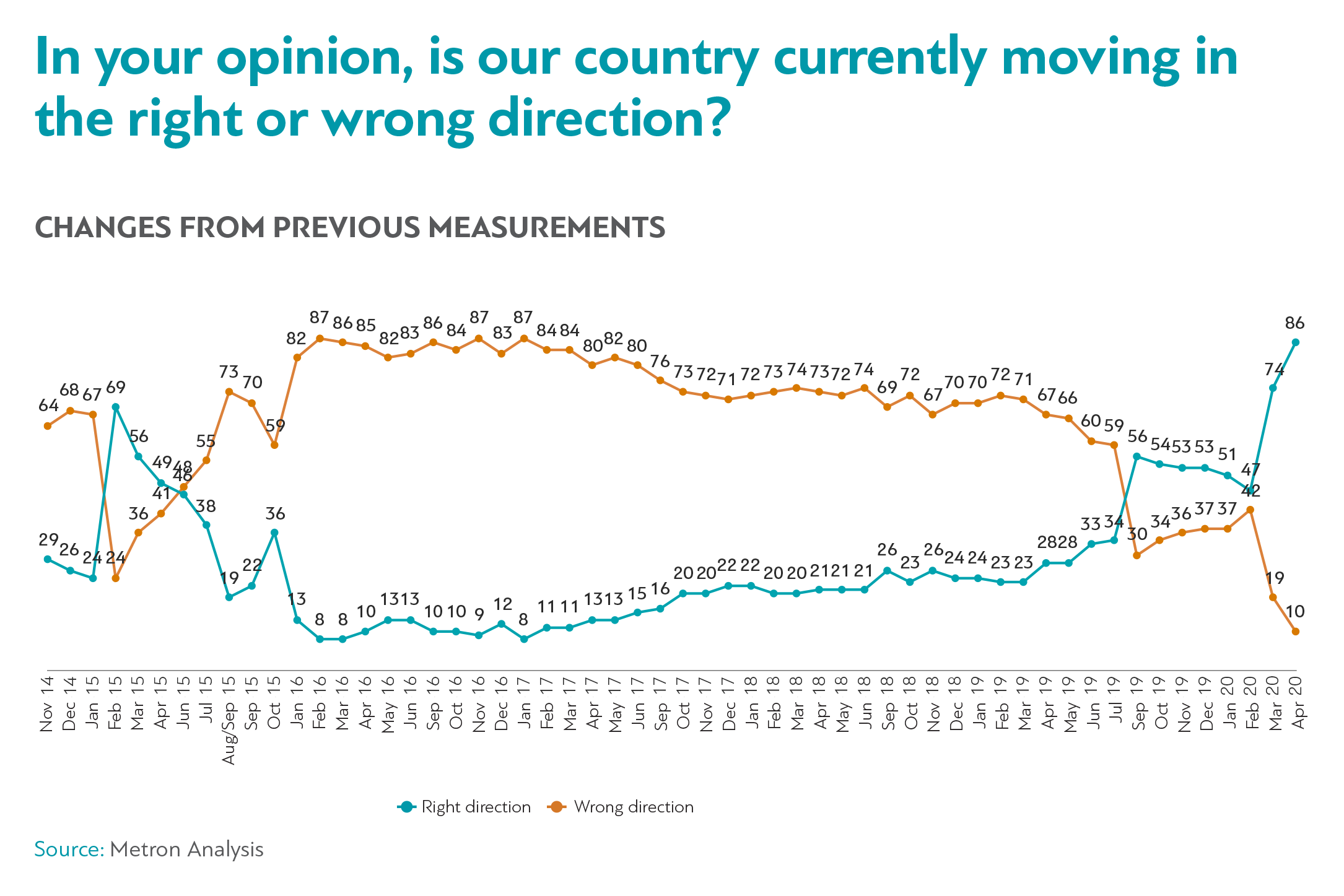

Every month for the past eight years, market research and opinion polling agency Metron Analysis has included a question in its surveys: "In your opinion, is our country currently moving in the right or wrong direction?" For the last eight years (with few exceptions in February 2015 and the fall of 2019), the majority of respondents consistently believed that things are not going well. However, the results of the present survey show that Greeks have never been as optimistic and confident about the future as they are today.

Today, 85.7% of Greeks believe that things are going in the right direction. This figure is unprecedented.

This answer sums up what citizens think about the overall situation in the country. Nowadays, in the face of one of the greatest crises of our generation, all demographic groups in Greece, people of all age groups, professions, educational backgrounds, income levels, social classes, geographical locations and political affiliations agree—for the first time—that things are “going well”.

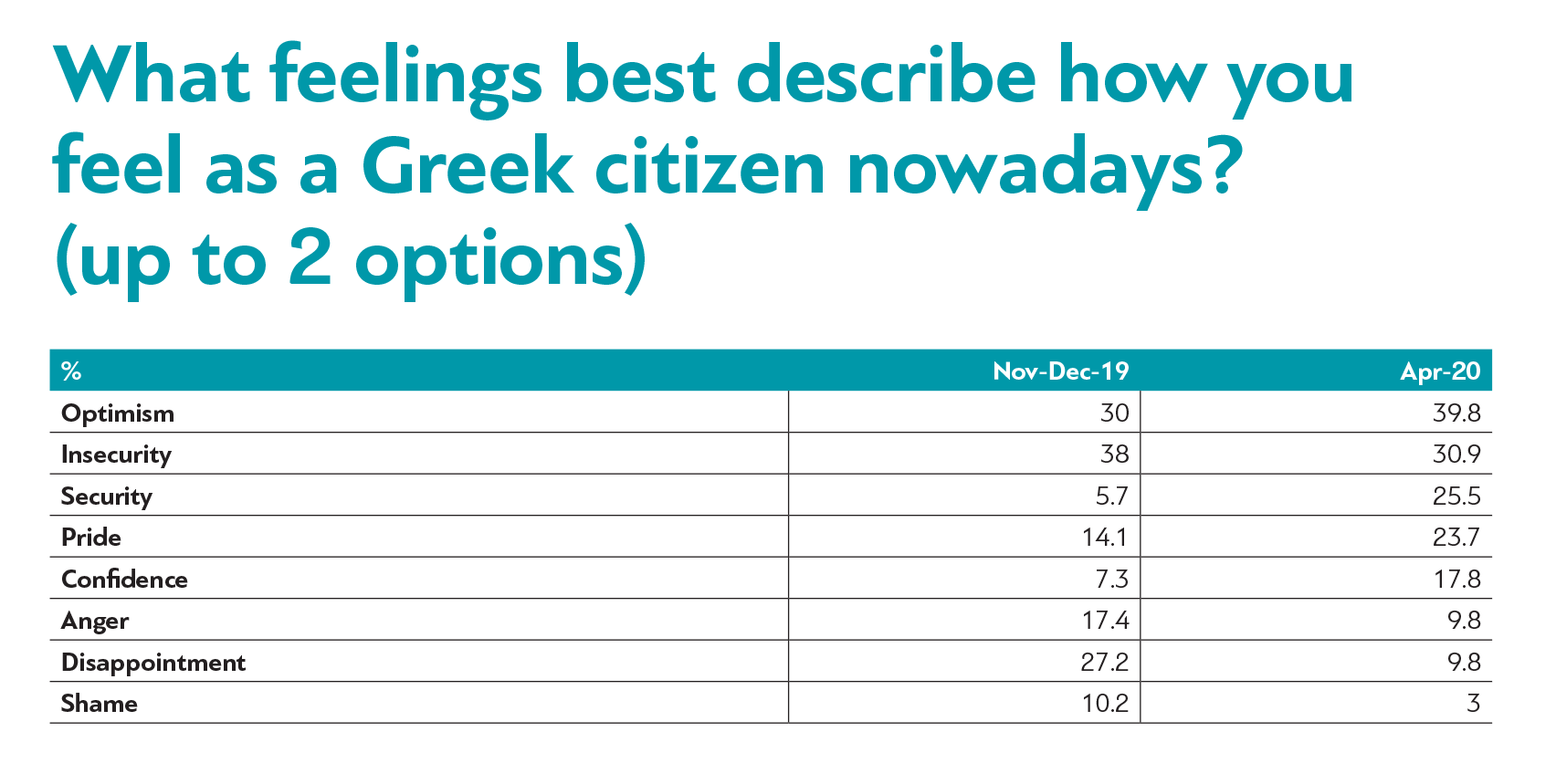

The same conclusion can be drawn from the powerful question on emotions. We asked the same question only five months ago, in "What Greeks Believe": "What feelings best describe how you feel as a Greek citizen nowadays?" The change in this short time is remarkable.

Within five months, after the crisis in Evros and, of course, while on lockdown, the dominant feeling changed from insecurity to optimism.

When asked to report their two main feelings at the moment, 40% of respondents stated "optimism" (up from 30% five months ago) while 31% chose "insecurity" (down from 38% in December). Nowadays, five times as many say they feel "secure"; more than twice as many say that they feel "confident". Almost half state "angry". Only a third say they feel "disappointed".

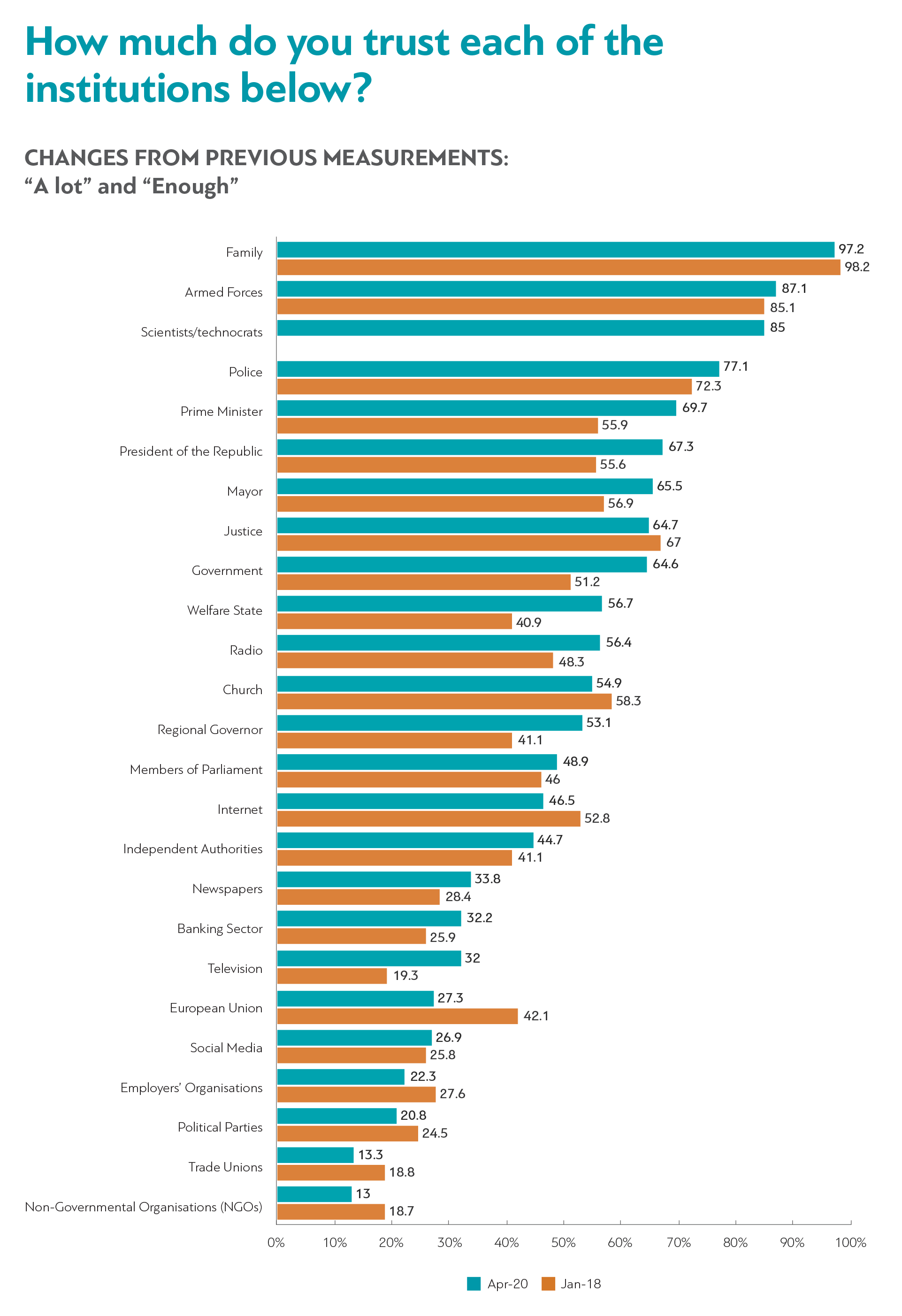

This reality is also confirmed by the reported feelings of trust towards institutions. We asked the same question in "What Greeks Believe" in 2018 and, now, the figures we got in many of the answers are vastly different. All state institutions enjoy significantly higher levels of trust today than they did 27 months ago: the Prime Minister’s office (+14%); the Presidency of the Republic (+12%, following the appointment of a new President); Mayors (+8.6%); Regional Governors (+12%); and the Government (+13%) in general. Confidence in the government today is at 65%. Interestingly, in similar surveys in France, the corresponding figure is 44%, while in Italy it is only 32%.

Citizens also trust the welfare state more (+16%) as well as the media (television +13%, radio +8%, newspapers +5%). As for the media, by the way, television and the internet are heralded as the main sources of information regarding the pandemic, while several citizens also state that they get their information mainly by their personal physician (the third most popular option).

The only institution that has become a lot less popular since 2018 is the European Union: only 27.3% state that they trust the EU today, down from 42.1% two years ago.

This time, however, we added another category: "scientists/technocrats." Some may notice that while 85% of Greeks say they trust scientists/technocrats (only lagging behind the armed forces and the family), only 55% say they trust the church. The result of this (admittedly untested) comparison is not unanticipated. In the 2017 World Values Survey (conducted by diaNEOsis in collaboration with the National Centre for Social Research), one question was: "Do you agree or disagree: whenever science and religion clash, religion is always right." At the time, only 21% of Greeks agreed — 66% disagreed. While a very large percentage of Greeks identify as religious and claim that they attend church often, trust in science and the experts seems to remain very high.

2.

So far, we have seen that Greeks are optimistic, full of confidence and with a renewed trust in the state institutions but also in the experts; that is, those who have mainly undertaken the project of dealing with the pandemic. But how do Greeks experience the crisis themselves? How scared are they? How threatened do they feel? And what do they do at home all day?

According to the results, one in ten Greeks (10.9%) state that they spend the quarantine period alone. The percentage is higher in the elderly: 19.3% of people aged 65+ live alone during this time.

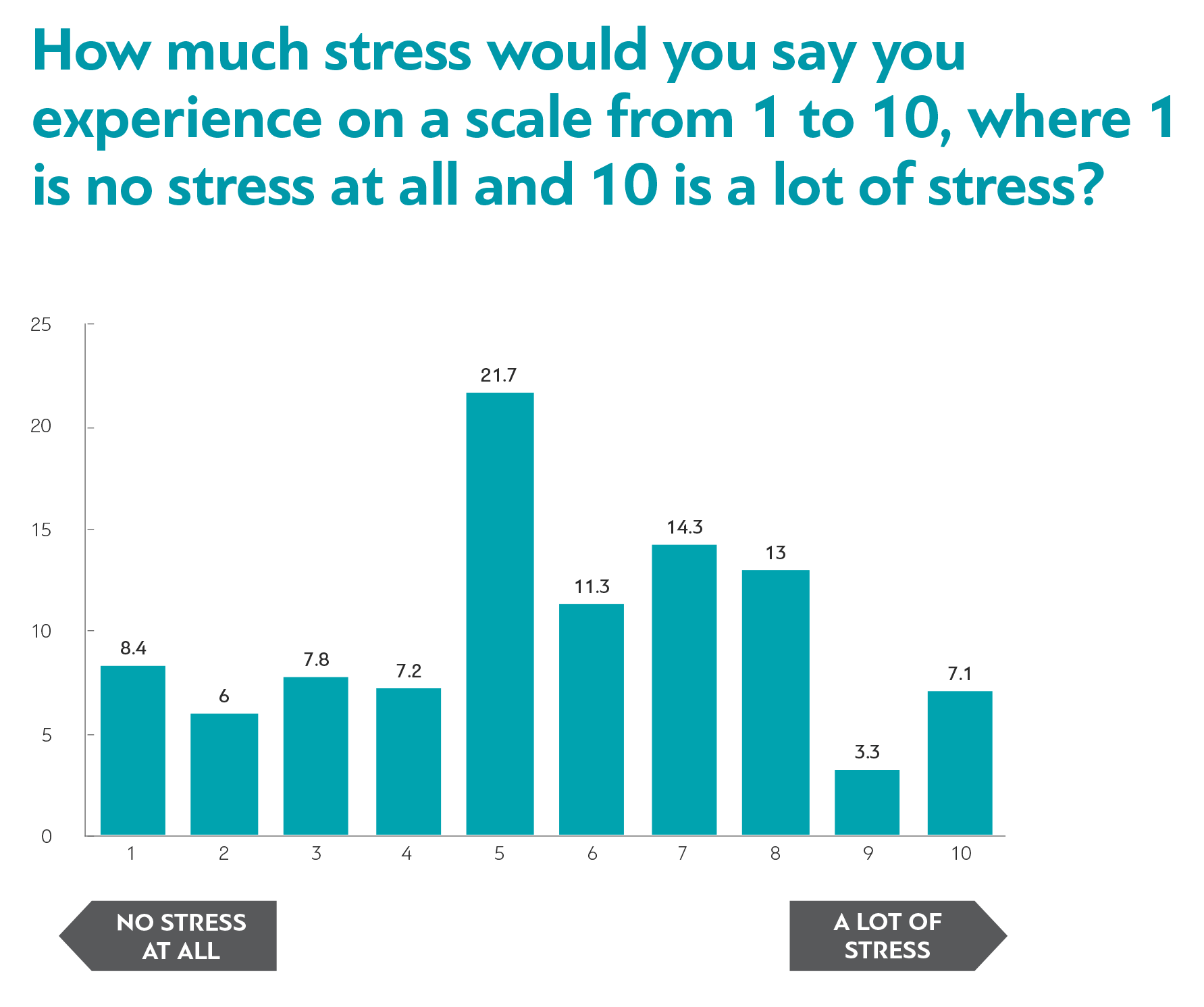

Greeks are also anxious. On a scale of 1-10, the average value is 5.5, but 37.7% of respondents say they are very anxious (from 7 and up).

What are the causes of stress?

62% of respondents say that there are people close to them who, in their opinion, are at risk of contracting the virus. However, only one in four (23.7%) fear that they are at risk themselves. 33% of people over the age of 65 are worried about this, but only 1.6% of young people aged 17-24 and 11% of those aged 25-39 are worried.

Still, 46% of the general population believe that they are at little or no risk.

One in five (21.3%) thought they were infected with the virus at some point—a figure about a thousand times higher than the confirmed cases in the country.

Most measures and much of the talk are about protecting social groups that are most at risk from the novel coronavirus. But how many belong to these "vulnerable groups"? According to the survey, 22.1% of Greeks say they belong to a "vulnerable group", i.e. consider themselves elderly or are people with immunosuppression or respiratory problems. Interestingly, 45.2% of respondents aged 65+ do not consider themselves part of society’s “vulnerable” group.

But to what extent do we really "stay at home"? We asked the respondents if they left their house in the past 24 hours and, if so, why. Apparently, two out of three Greeks (63.6%) did, in fact, leave their house. Of them, 61% say they went to the supermarket or to the pharmacy; one in three (37.6%) to exercise or to walk a pet (text "6", that is); and one in four (24.2%) went to work. As expected, many went out for more than one reason.

It is worth noting that while three out of four men have stated that they have left their home in the last 24 hours, only half of the women have done the same. As one would expect, other groups below the national average were vulnerable people and those over the age of 65. In both cases, about half of them left the house.

And what do we do while we are at home? The activities that Greeks do more today than they did 3-4 months ago are, more or less, expected: they spend time with their family (64.4%), watch TV/movies (56.8%), do housework (52.8%) and use social media and the internet (47.1%). One in three (36.6%) state that they work less than before, while—a little surprisingly—those that exercise less (30.6%) are more than those who state that they exercise more (24%).

3.

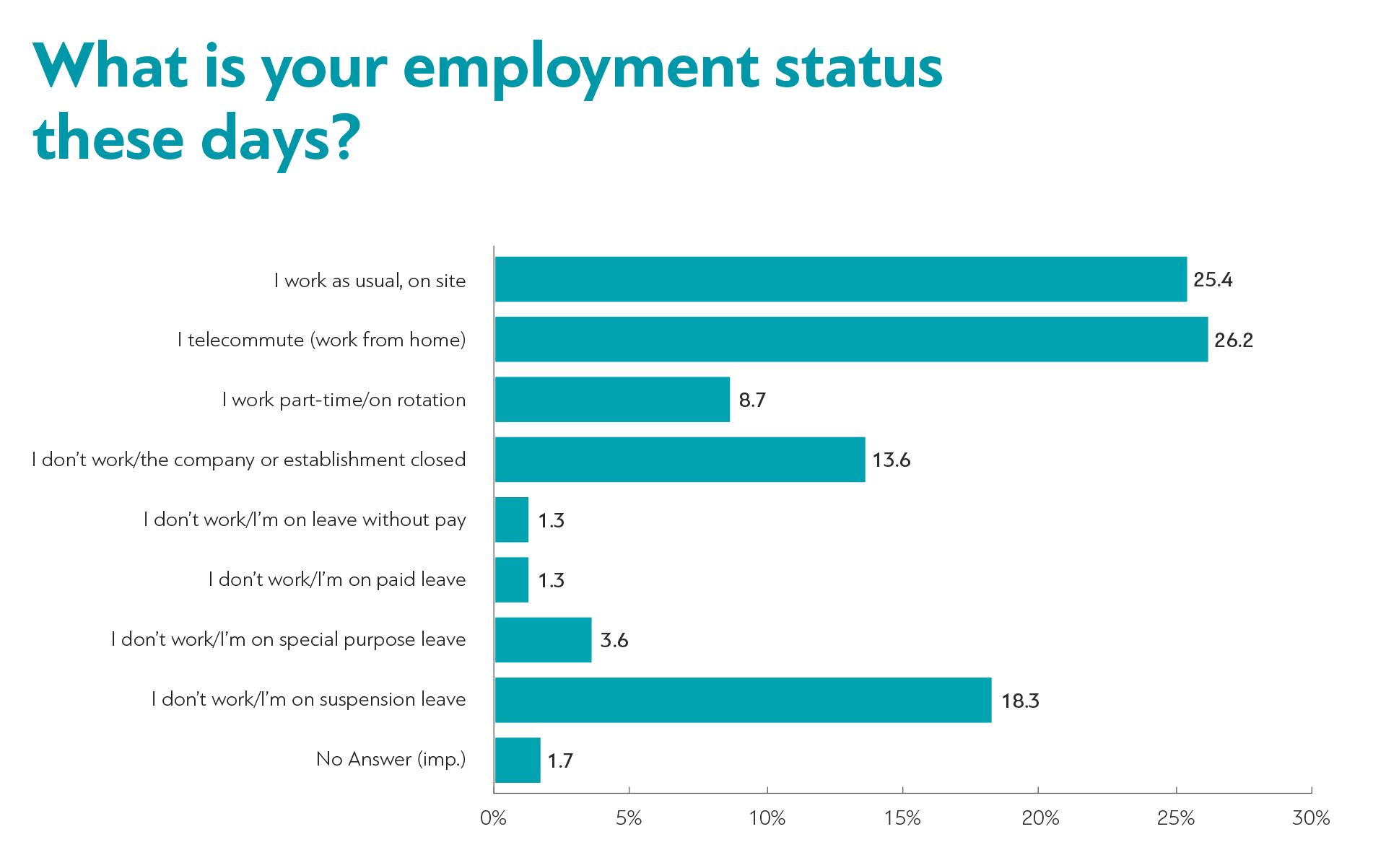

As we have seen, one in four Greeks states that they left their home in the past 24 hours to go to work. This is corroborated by the figures on self-reported employment status.

About half of the economic activity in the country is on pause: of those working in Greece, one in four (25.4%) works as usual, another one in four (26.2%) telecommutes, and the rest either work part-time or are under some scheme of leave or suspension and do not work at all.

So, naturally, 41% state that their income has decreased since the coronavirus lockdown.

Besides, 11.4% of unemployed respondents state that they lost their jobs after March 1, 2020. This is not a small percentage. If this figure is accurate and given official data on unemployment in the country, in the past month some 100,000 people may have become newly unemployed.

As expected, most believe that the crisis will have a significant negative impact on their financial situation (57.9%) and an even bigger one on the economy (84.3%). Moreover, they believe that it will have negative long-term effects on the "way of working", "physical health", "education" and, of course, "mental health" (63%).

However, the vast majority (75.3%) believe that in the long run, the pandemic will positively affect confidence in the health system, as well as solidarity (66.8%), confidence in the state (57.2%), family relations (52.3%) and, perhaps paradoxically, confidence in private initiatives (44.2%)—although around the globe the burden of dealing with the crisis so far is mainly borne by the states and not the private sector.

And what do Greeks expect for the future?

A very high 67.9% of respondents believe that we will return to "some normality" by September 2020. Almost 40% believe that we will return to normality "in the next two months".

By the way, one in four Greeks (24.1%) say that, if there were no imposed measures in place, they would return to their usual daily activities today. In contrast, another one in four (24.5%) say they will only return when a vaccine for SARS-Cov-2 is released.

As the measures of lockdown have now started to ease, and as the discussions over what "the next day" will bring are ongoing (whenever that may be), what conclusion can we draw about the lives of Greek people from these first clues?

"The pandemic and restrictive measures are radically changing the way of life, even if these changes are contextual," writes Stratos Fanaras of Metron Analysis. "This change is taking place in a coordinated manner, without social panic or fear." Through this transformation, there appear indications of other, more complex shifts on issues such as institutional trust, management of unexpected challenges, our individual resilience and that of public bodies and businesses, our mental resourcefulness and endurance. Some of these changes are well understood -such as, for example, the issue of trust. "To face the forthcoming challenges," Mr Fanaras continues, "we need to turn managerial trust into an institutional trust." The effects of the rest are more difficult to predict.

Take another finding from this survey: 85% of Greeks say they have not shaken hands with someone outside their household for longer than a month. For most of us, it's been a month since we touched another human being. Where does that leave us? This is a profoundly new experience for most Greeks -and most people on the planet. The inevitable deeper consequences are impossible to predict yet. After all, we are only at the beginning.