The legendary Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes famously said that taxes "are the price we pay for a civilized society". In a recent diaNEOsis opinion poll, respondents seemed to agree: 85,5% stated that they consider tax evasion to be equivalent to theft. At the same time, however, 35,1% acknowledge that they would readily evade their taxes if the opportunity arose, because ‘everyone does it.’

Tax Evasion in Greece - The Full Study (PDF, in Greek)

Tax evasion is one of the most important problems facing any democratic state. It appears to be even more acute in Greece; according to several studies, tax evasion in our country is substantially higher than in other developed countries.

In this study, we cooperated with Ernst &Young in order to map out the problem of tax evasion in Greece, analyze all available data to reach conclusions about the problem’s scale and nature, and arrive at a series of policy recommendations to help curb it. This is a summary of the basic results.

How much tax evasion is really going on?

The exact scale of tax evasion in Greece is obviously unknown. We can only rely on estimates that calculate its scale based on indicative data but, by definition there is no available information to measure its exact size. We gathered estimates that have been published on all different types of tax fraud, and we arrived at a range that may appear arbitrary to a certain extent, but which does present the closest estimate one can get from data that is available. According to the studies:

Revenue lost due to personal income tax evasion ranges from 1.9% to 4.7% of annual GDP.

An additional 3.5% of GDP is estimated to be lost due to Value-Added Tax (VAT) fraud.

Losses from alcohol, tobacco and fuel smuggling amount to about 0.5% of GDP.

For legal entities, revenue lost from tax evasion and tax avoidance is estimated at around 0.15% of GDP.

Consequently, the scale of tax evasion in Greece can be relatively safely estimated at somewhere between 6% and 9% of GDP, which amounts to something between €11 and €16 billion a year.

The study of different types of tax fraud can provide some extremely interesting insights, debunking several long-standing myths. For example:

Who pays taxes in Greece?

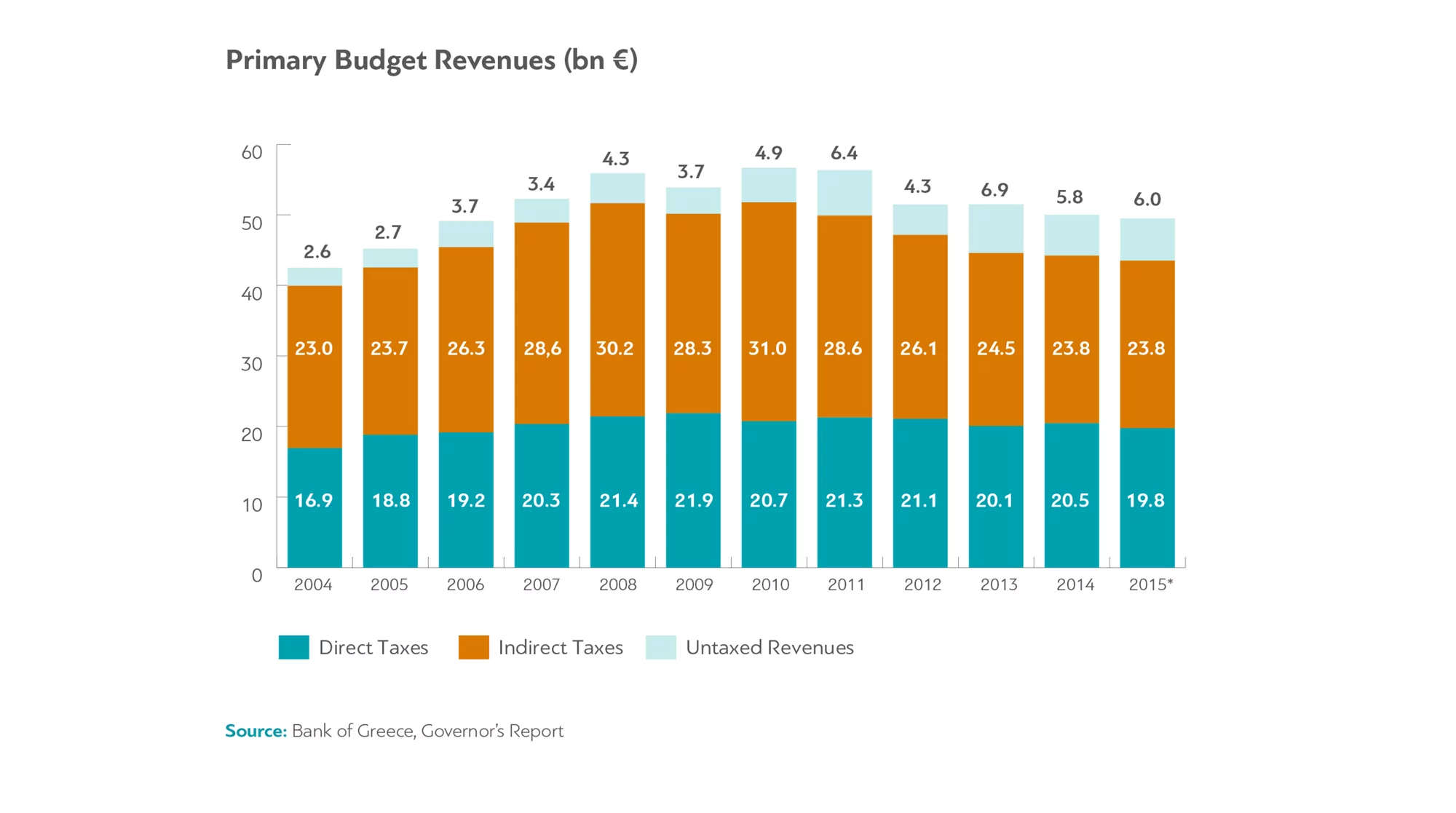

The Greek state's annual revenue hovers around €50 billion. This is income that, along with social security payments, insurance revenues, and loans from the European Union together must cover all state expenses. These expenses include the government's operating costs, repayment of the country's loans (around €12 billion a year), pension payments (€28 billion a year), salaries of public employees (around €15 billion a year) and, according to the memoranda that have been signed with Greece’s creditors, significant annual primary surpluses.

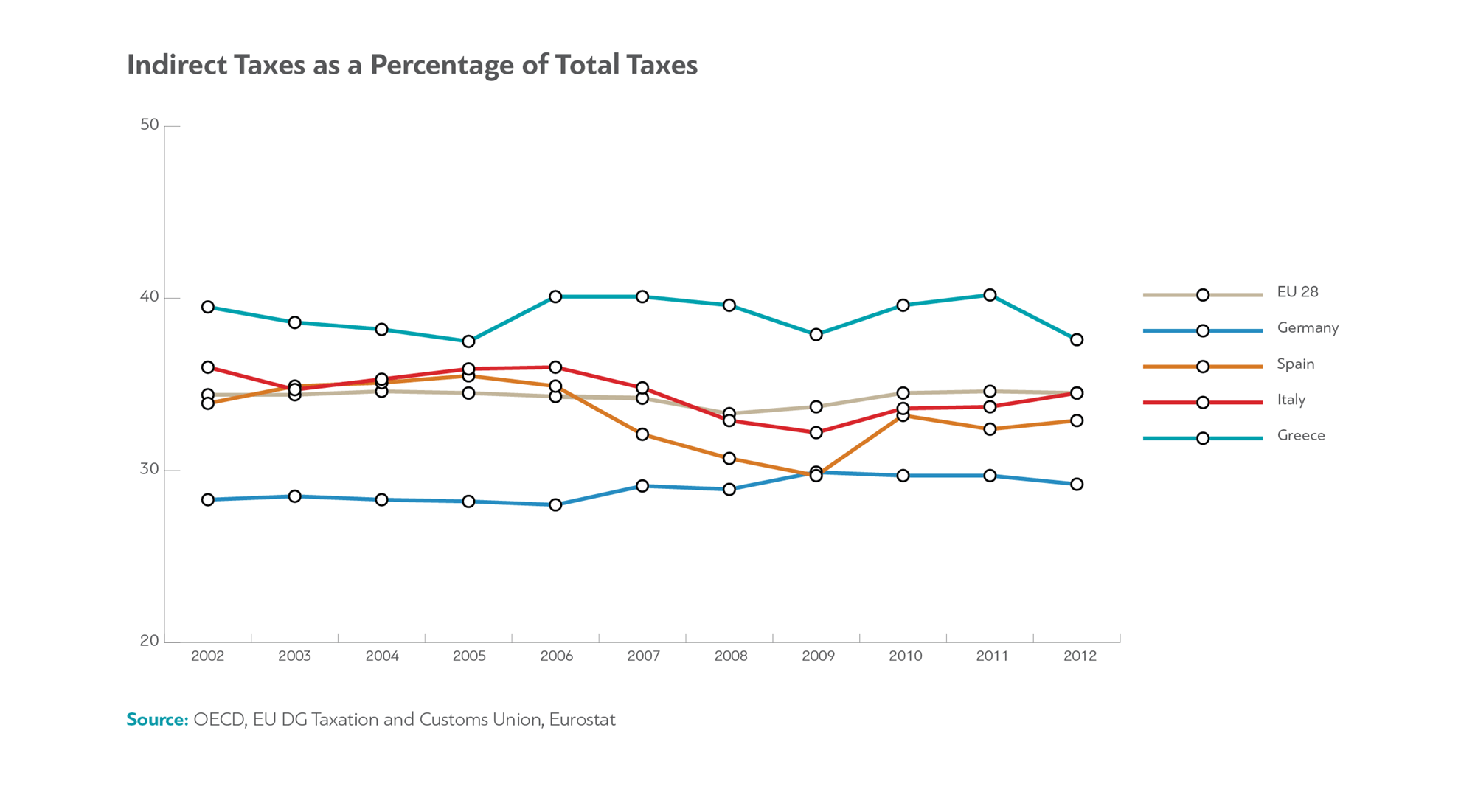

According to the most recent data from 2015, 88% of the state’s revenue (not including insurance revenue collected by the social security funds) comes from taxation. Direct taxes bring in around €20 billion, while indirect taxes (VAT, fuel tax, tobacco tax, etc.) bring in around €24 billion. This is important. Indirect taxes are considered more ‘unjust’ because they affect the rich and the poor equally. The tax systems of most developed countries rely more on direct taxes for that reason. It is mostly developing or third world countries that rely more on indirect taxes.

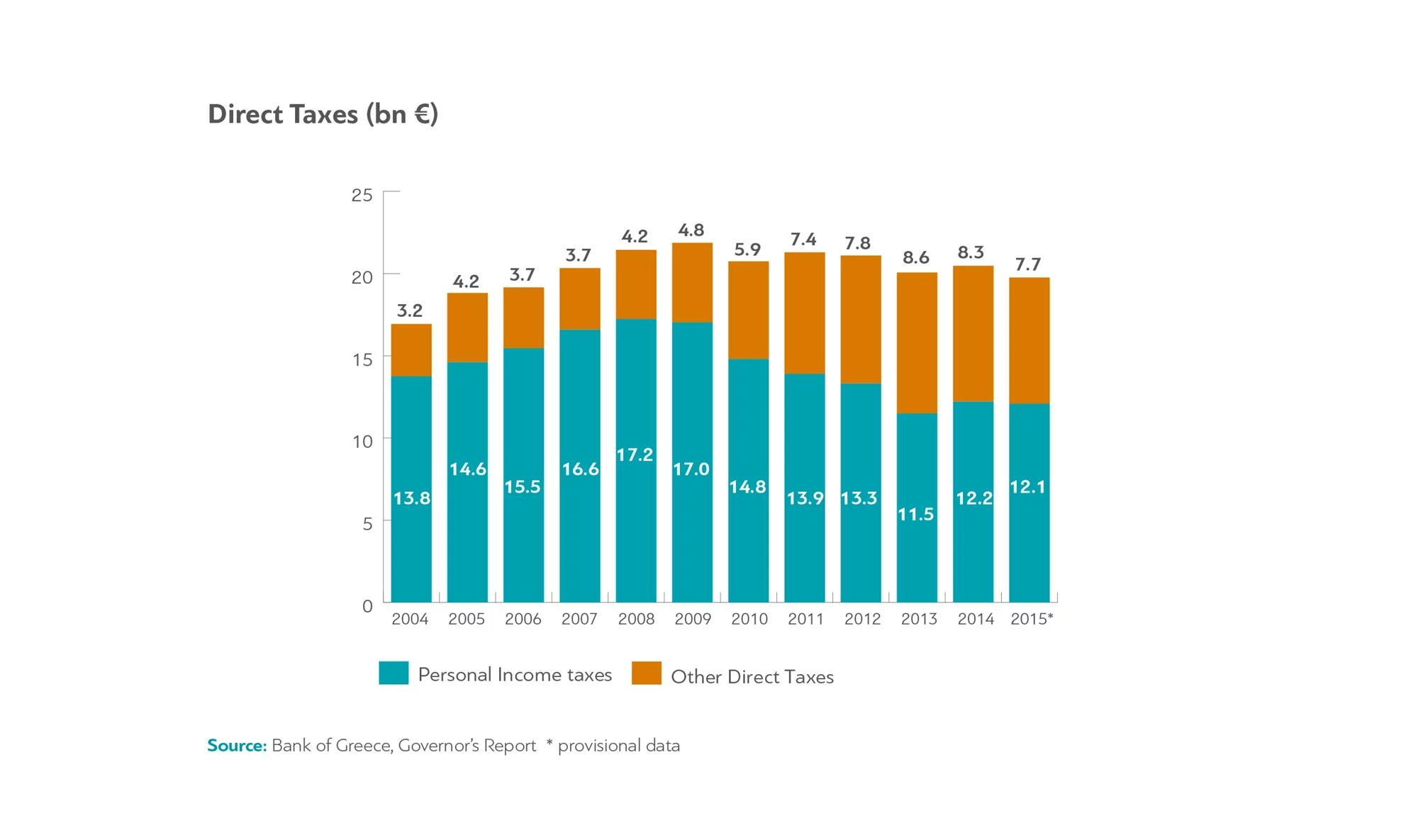

The country’s revenues have been more or less steadily decreasing since 2010, with the largest decrease occuring in indirect tax revenues. There was a rapid decline in income tax collected (from 17.2 billion in 2008 to 12.1 billion in 2015) – which is to be expected, since citizens’ incomes have decreased dramatically. At the same time, however, during the crisis, direct tax rates increased, and new direct taxes were also introduced (solidarity tax, Single Property Tax-ENFIA), which softened the state’s losses but increased the tax burden for everyone -primarily for the poor.

During the crisis, citizens pay around the same direct taxes that they paid before, despite the fact that they have much lower incomes than before.

But who is paying taxes? It appears that, up until the first few years of the crisis, it was generally the rich who were bearing the county's tax burden.

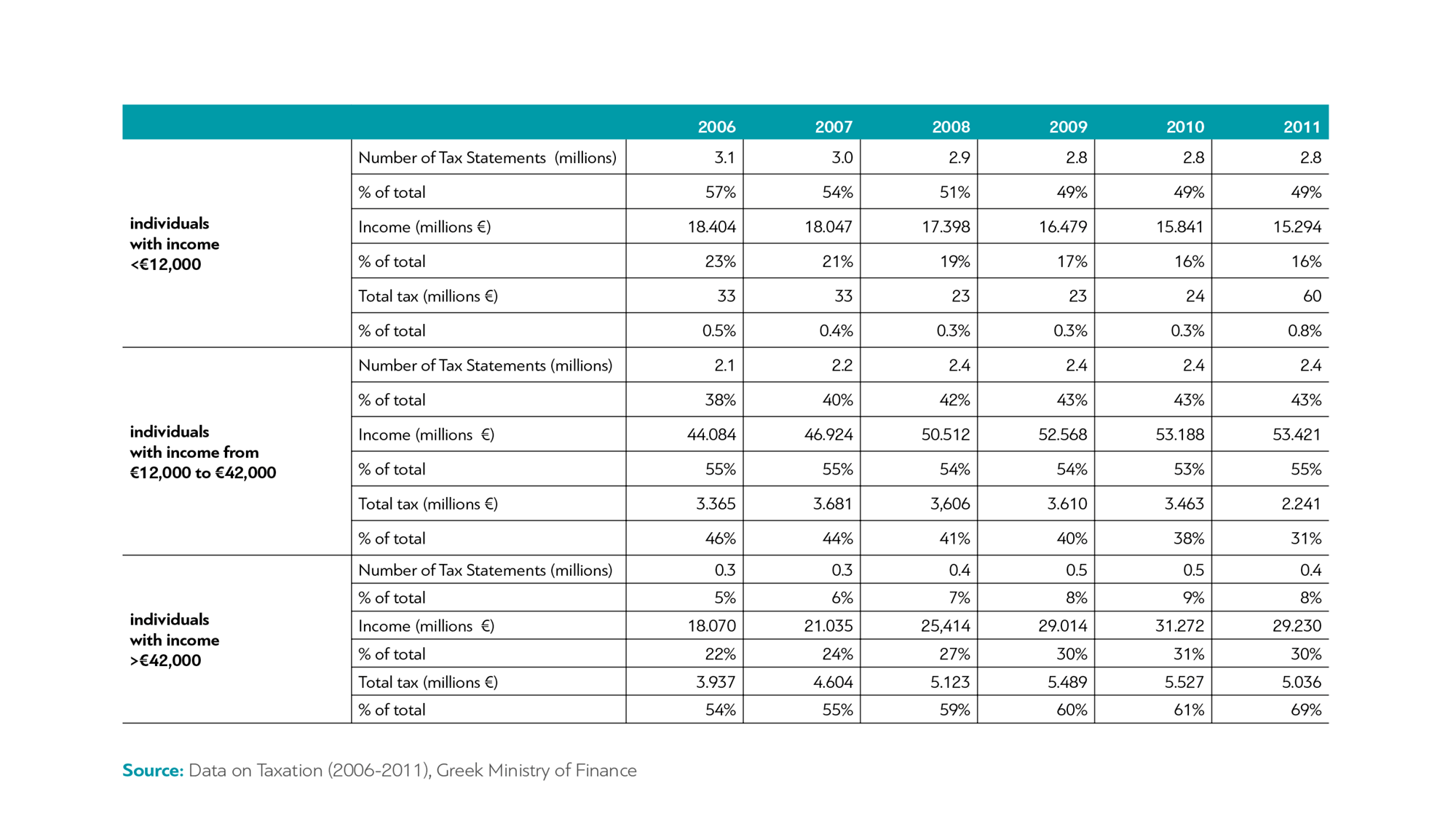

In Greece in 2011 – the last year for which analytical official data from the GSPW are available – 5.7 million tax returns were filed, a number that has remained more or less constant for the past ten years. Nearly half of them (49%) featured declared incomes below €12,000. 64% of the self-employed declared income below the tax-free limit of €12,000 (they declared a mean income of just €4,300). These taxpayers combined paid less than 1% of the total tax revenue. In other words, 2.8 million citizens paid a total of 60 million euros in taxes –€21.4 each. On the other hand, the 8% of taxpayers who declared income above €42,000 -around 400,000 citizens in total- paid 69% of the total personal income taxes.

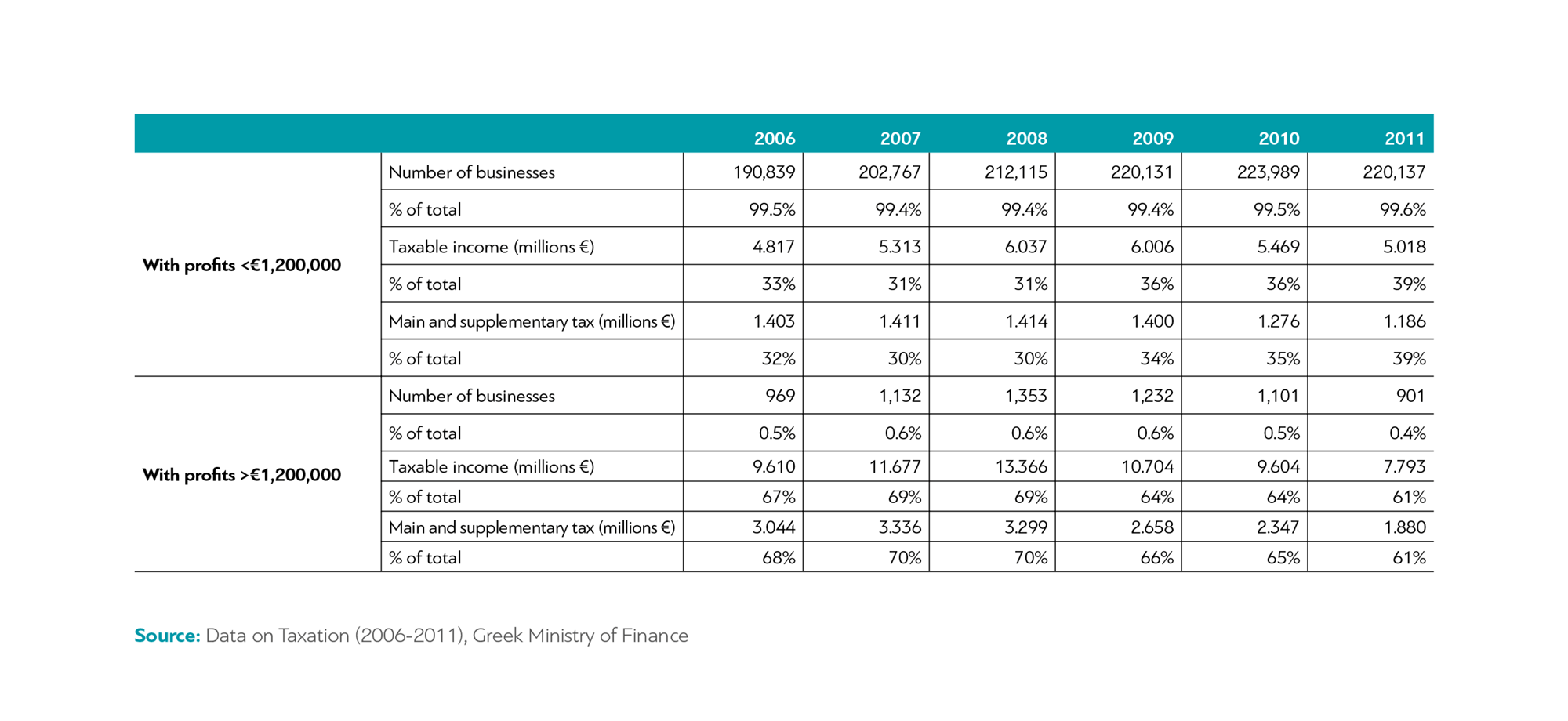

The situation is similar when it comes to businesses. In Greece in 2011, there were 220,000 businesses that declared less than 1.2 million euros annual profit, and just 901 businesses that declared greater income. The latter category, which makes up 0.4% of Greek businesses, paid 61% of taxes. Companies from the former category were paying on average €5,400 a year, while companies from the latter category were paying €2.1 million.

In other words, in 2011, 8% of taxpayers paid 69% of the personal income tax, and 0.4% of businesses paid 61% of legal entity income tax in Greece.

The "rich" were bearing the country’s tax burden. And who are these ‘rich’? In their large majority, they are highly paid salaried workers and large businesses. The great majority of revenue from income taxes came from them. This appears to be changing, however.

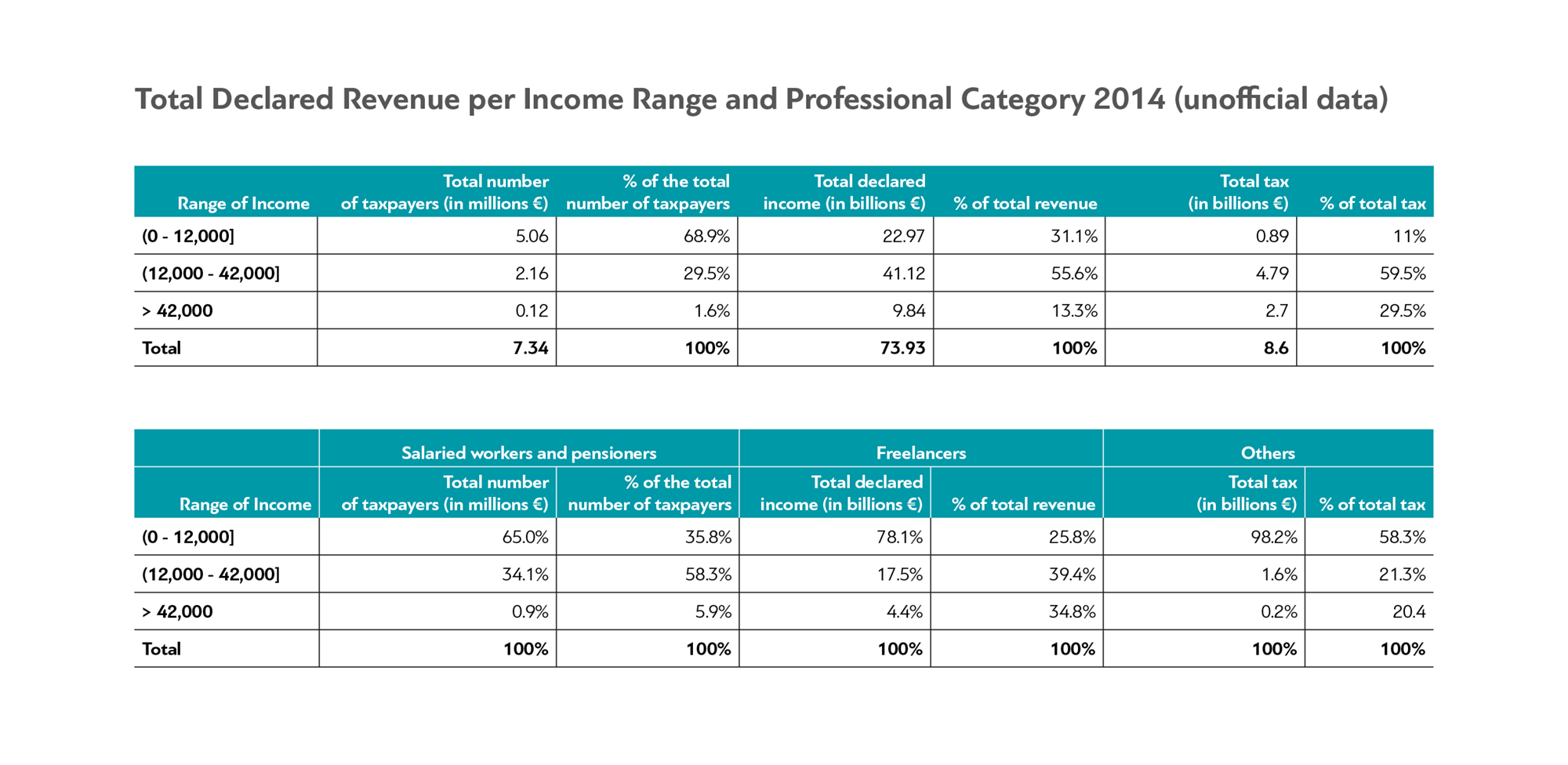

According to unofficial data available to diaNEOsis for the 2014 tax year, there has been a dramatic downward shift in income (individuals who declare income above €42,000 are no longer 8% of total tax payers, but merely 1.6%) and there has been a strong shift of the tax burden towards the middle class.

Who evades taxes?

There is a truth that is more or less valid throughout the world: the self-employed and small businesses avoid paying their taxes. From the United States to Germany, and from Italy to Bulgaria, there are small businesses and many freelancers that fail to accurately declare their true income to authorities. Unlike salaried workers or large businesses, they are able to hide their income because the likelihood of detection is very low and the incentive to issue invoices and to declare every cent they make is smaller. Despite the tax-paying culture and the enormous fines, small businesses in Germany can avoid issuing receipts for some of their sales, without any consequences.

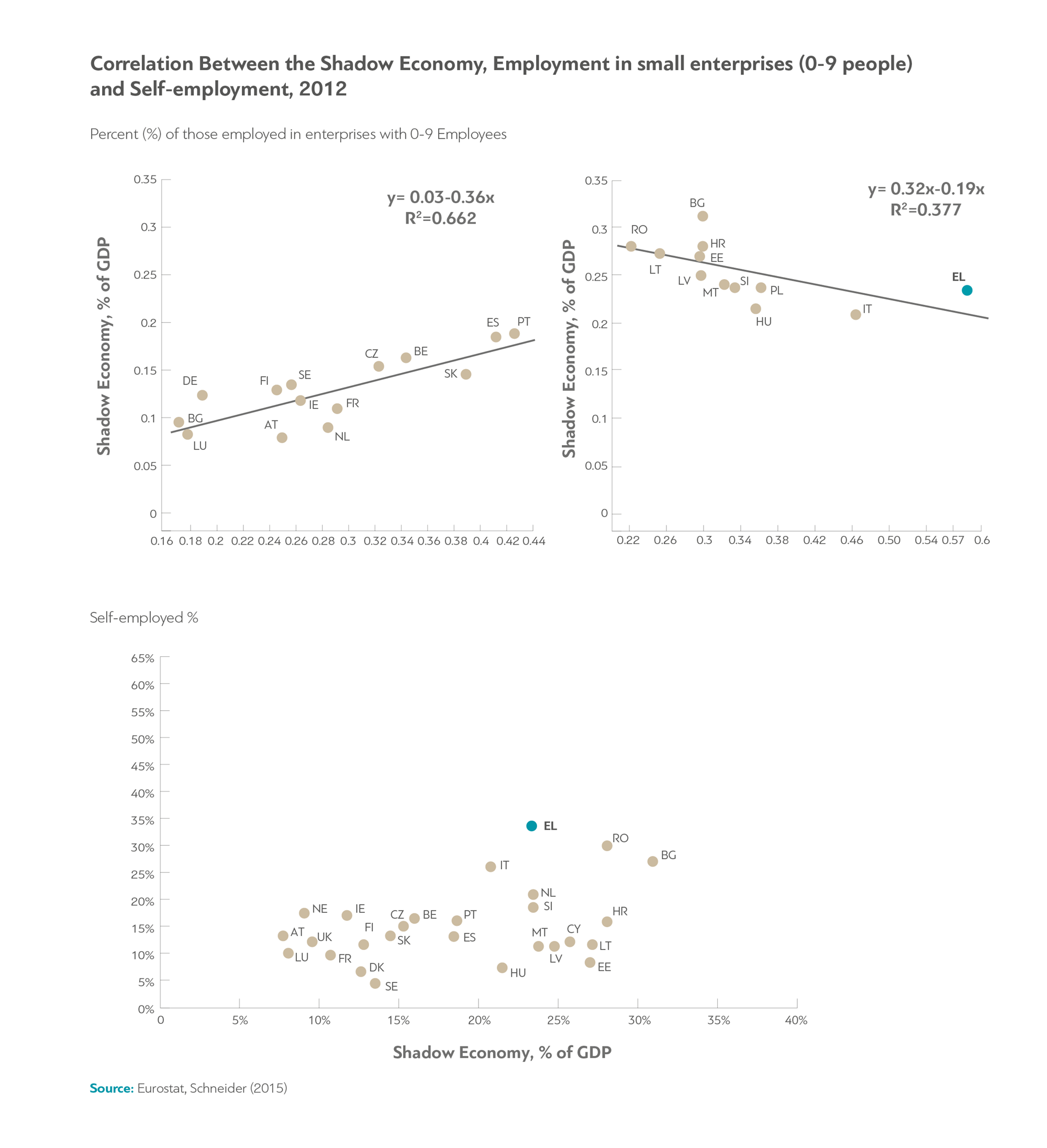

This phenomenon has a relatively small impact on tax revenues in most developed countries for one simple reason: The number of very small businesses in those economies is lower, and the self-employed represent a smaller percentage of the workforce. This is a critical characteristic of the Greek tax problem: in Greece, the percentage of the self-employed is twice as high as the European average. According to studies, the self-employed hide around 57-58.6% of their income, while salaried workers are only able to hide about 0.5-1%. Very small businesses (0-9 people) in Greece employ a staggering 59% of all workers in the country -double the EU average. The percentage of workers in large businesses (with more than 250 employees) is just 13% in Greece, compared to 33% in the EU. This is a very serious problem, because small businesses can more easily employ undeclared workers, avoiding tax and social security payments, while issuing fewer invoices and paying less VAT.

How do the rich and big corporations avoid paying taxes?

As a general rule, as we saw above, the "rich" have been paying most of the country's taxes until recently. At the same time, however, wealthy individuals (a very, very small subset of the 400,000 who declared revenue above €42,000 annually), have a series of tax avoidance tools at their disposal, like the foundation of offshore companies, shell corporations, trusts and other legal entities. According to studies, 8% of global taxpayer wealth is hidden in tax havens. In Greece, the most common tools that have been used to evade paying taxes are the transfer of real estate to offshore companies (a phenomenon that is being partly tackled by imposing a specific tax on real estate), and the transfer of tax domicile, sometimes even with artificial means.

Legal entities evade taxes in a series of ways. The most common is the issue of false invoices -a common practice especially in small and medium-sized companies-, which aims to both reduce the income tax and the VAT companies need to pay, as well as showing false losses. There are several other tricks companies use to avoid paying VAT and fraudulently reducing declared profits.

Large corporations cannot, as a rule, use such means to avoid taxes, so they appear to pay the majority of taxes declared by legal entities in the country. However, there are other means of tax avoidance for large multinational corporations. Transfer pricing within the EU and the so-called carousel fraud (or "missing trader" fraud), which are analyzed in the study, are the most common. Of course, individual countries cannot easily address these practices on their own. Around 60% of global trade takes place within multinational groups with intra-group transactions, where there is ample room for tax avoidance. It is estimated that around 4-10% of the worldwide corporate income tax is not paid every year. Curbing this phenomenon is a major challenge and requires cooperation and coordination among many nations and cross-border organizations.

In Greece, of course, as we have mentioned before, there are only 901 ‘large’ corporations (we define as "large" those with annual profits over €1.2 million) – just 0.4% of the total. Some of these definitely could use these methods to avoid some of their tax burden. At the same time, however, these are the enterprises that pay 69% of corporate tax revenue in the country, a total amount that is around 4% of state revenue, approximately €1.9 billion. The revenue lost by the state from tax avoidance by companies like these is difficult to calculate, but according to conservative estimates, as we said above, it could amount to about 0.15% of GDP.

It’s obvious that tax evasion/tax avoidance at this level, though serious, is on the one hand very difficult to identify by individual states and on the other, much smaller in scale than tax evasion by the self-employed and small businesses.

The shadow economy

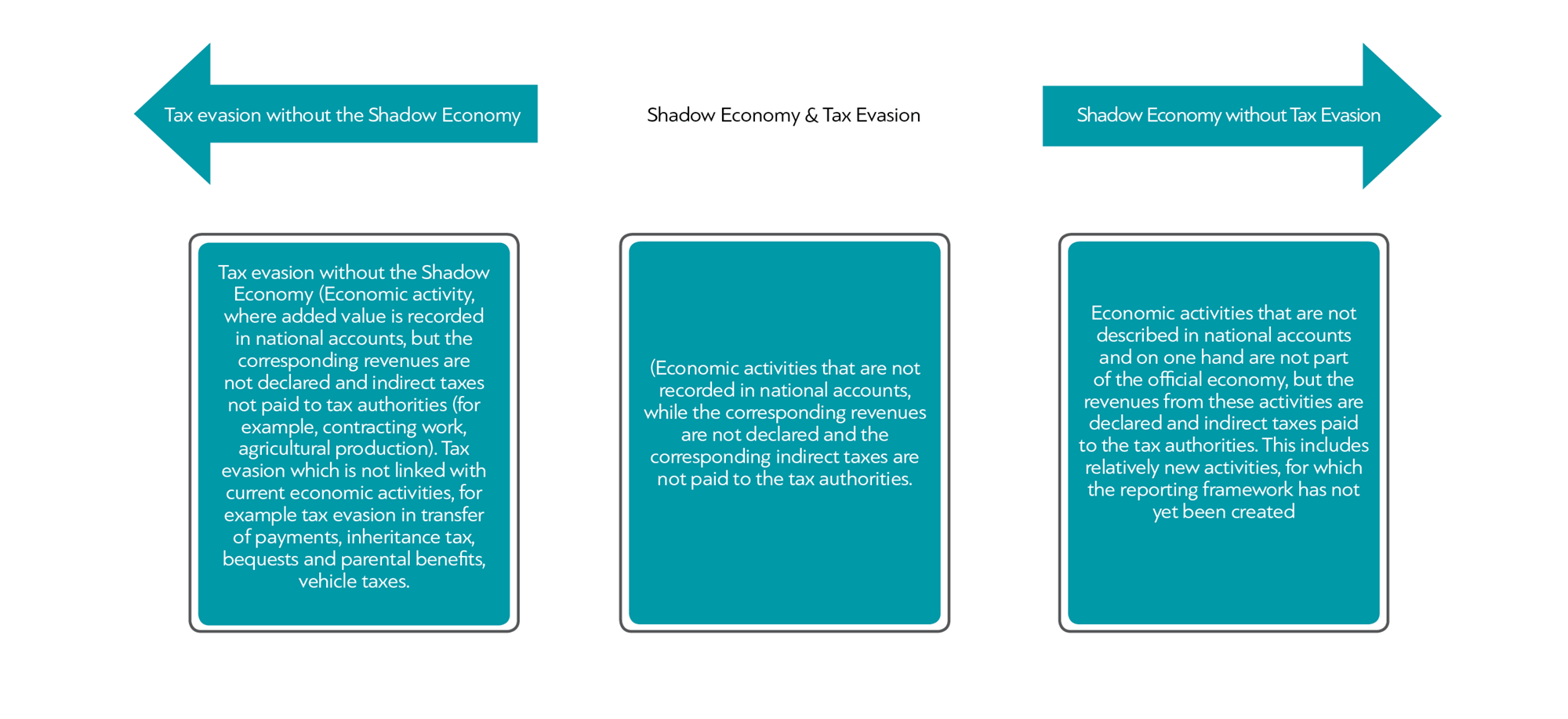

The shadow economy is the sum of undeclared economic transactions in an economy. It is not synonymous with tax evasion. It includes a series of undeclared ‘hidden’ secret activities that range from smuggling, to private lessons, to casual restaurants that do not issue receipts.

In contrast to what many believe, the largest part of the shadow economy (around two thirds of it) is attributable to undeclared employment - and that is one sector that has increased rapidly during the crisis. In 2010 the Hellenic Labour Inspectorate audited 22,000 private enterprises and found that a quarter of employees had not been declared. Since the crisis began, this number has increased dramatically: by 2013 it had reached 40.5%. According to research by the Ministry of Labour, 27% of those working undeclared had asked their employers to allow it.

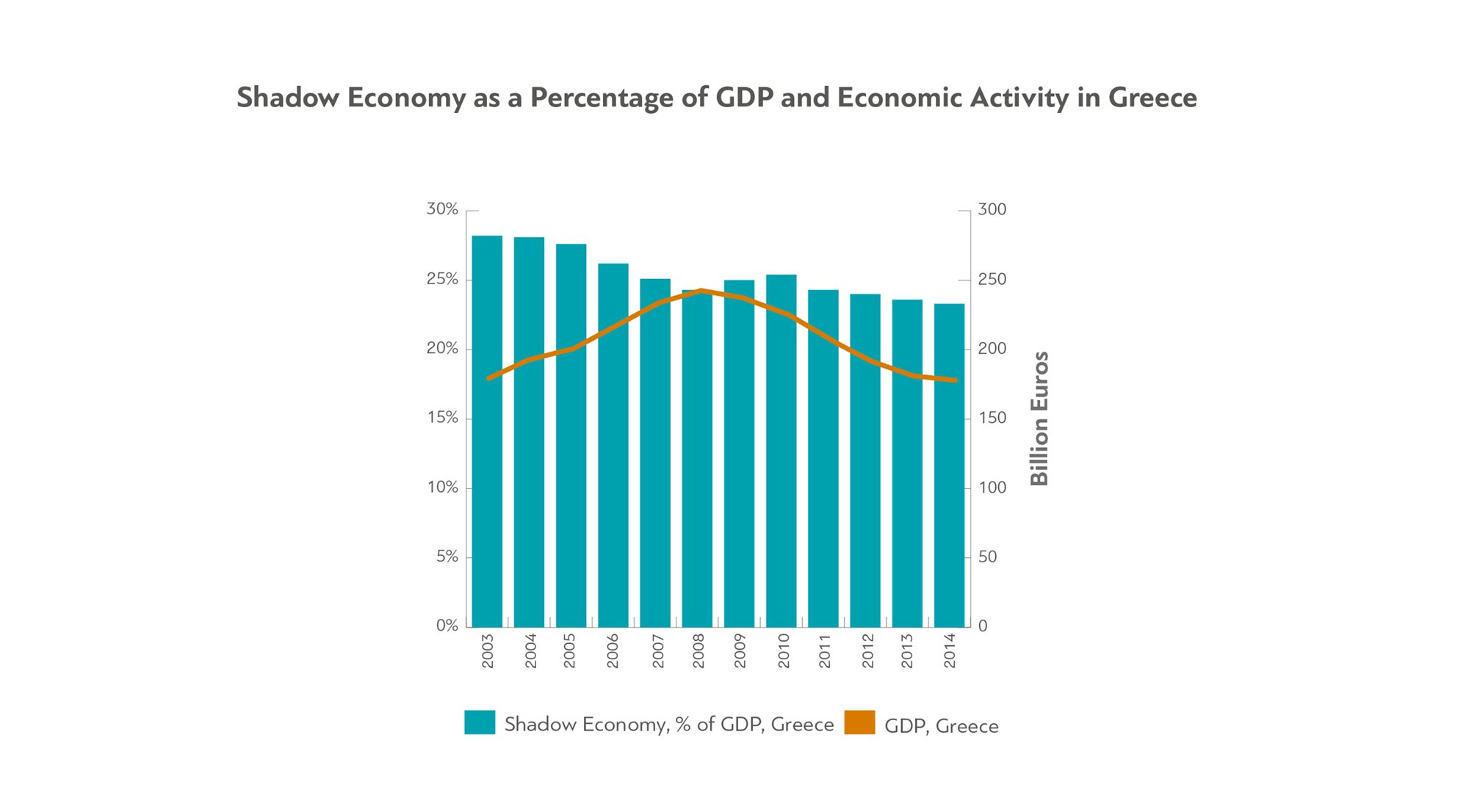

In Greece, various studies have calculated that the shadow economy makes up between 20 to 30% of GDP, an unusually high percentage for a developed country. It is estimated around 4-5 percentage points above the average of the European Union. During the crisis it has decreased across Europe. For 2015 it was calculated to make up around 22.4% of Greece's GDP which, in absolute numbers, comes out to about €40 billion.

Why is tax evasion possible?

According to the relevant academic literature, there are three parameters that determine the level of tax evasion in an economy:

- The level of tax rates.

- The likelihood of detection and punishment.

- The level of fines imposed.

Whether or not a citizen or a business will evade taxes is a decision that is essentially affected by these three factors. If tax rates are low, the motive for tax evasion is smaller. If tax enforcement mechanisms of the state are ineffective, or if the penalties in case of arrest are negligible, the motive for tax evasion increases. This is not true only in Greece – tax evasion is a universal phenomenon. These parameters apply everywhere.

If we focus more on the Greek case, we can identify 8 main causes for tax evasion:

- The complexity of the tax system

- Legal uncertainty for taxpayers and employees of the tax administration

- Repeated tax hikes

- The lack of political will to address the problem

- Technological failures

- Bureaucracy

- Structural distortions of the Greek economy

- Tax culture

The first two problems are obvious, and linked to each other. Since 1975, Greece has voted in 250 tax laws and 115,000 ministerial decisions. Within the last 30 months alone, 10 tax laws with 117 articles and 17 other laws with 71 tax provisions were voted in. For these provisions 111 ministerial decrees and 138 explanatory circulars were published.

It is clear that this complexity makes operating the tax collection mechanism exceptionally difficult. At the same time it inevitably causes uncertainty for tax payers and tax administration employees alike. Even tax experts often have a limited knowledge of what is legal and what is not. And, of course, among all this complexity, there exist opportunities and incentives for corruption.

The third cause is equally clear. During the crisis, the income tax on individuals has increased and the tax-free limit has been reduced. The tax-free limit has also been abolished for the self-employed, who now have to pay a larger percentage of tax in advance. The corporate income tax has increased, in the form of an advance tax burden. Finally, the rates of the "special solidarity tax", property taxes, the VAT rates on products and services, as well as consumption taxes on alcohol, tobacco and fuel have all increased.

It is commonly believed that by now taxes in Greece are exceptionally high. Indeed, the OECD calculated that Greece’s tax burden in 2014 increased from 34.4% to 35.9%. There is a threshold, predicted by the so-called "Laffer curve" (named after the economist who drew it on a napkin in order explain the phenomenon to Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, members of the administration of US President Gerald Ford in 1974) above which tax revenues decline. According to a European Commission study, this limit for countries within the EU is at 54% for individual income tax and at 72% for income tax on legal entities. This is considered an exceptionally high rate, much higher than the rates in over-taxed Greece (personal income tax in 2012 was calculated at 38%, for example). Nevertheless, this does not necessarily mean that there is room in the Greek economy for further tax rate hikes. The same European Commission Study estimates that for countries with a sizeable "shadow economy", the Laffer curve is shifted downward. For countries like Greece, the threshold of individual income tax is at 39% - very close to the current rate. This means that a further increase of tax rates in Greece would have little effect.

Of course, high tax rates have other serious consequences, beyond their reduced efficiency. They are a serious disincentive for investment, they rapidly decrease the competitiveness of domestic enterprises, while they also negatively impact consumer spending (sales of alcoholic drinks in Greece have decreased 45.7% between 2009-2012).

But why doesn’t the Greek state address the problem of tax evasion? Despite long-term commitments by all political forces that have ever participated in elections in recent history, the results have been meager.

The digitisation of the Greek tax system has lagged significantly. For example, electronic submission of corporate tax returns became possible only in 2013, while a series of processes continue to require the physical presence of taxpayers at tax administration offices. Information systems are not linked to one another, databases are not digitized or up to date, information management systems are not regularly updated: there has been a series of bureaucratic failures, simple things that other countries managed to solve many years ago.

What are the solutions?

The fight against tax evasion is a challenge for every state in the world. Both the European Union and the OECD have developed tools to fight tax evasion, and there is a rich history of policies fighting the problem in other countries, which is worth studying. The extensive use of ‘plastic' money and the extension of electronic transactions have been tested in many countries (from South Korea and Argentina to the Netherlands and Sweden). Modernization of the tax administration has been implemented in a remarkable way in Singapore, Brazil and even Bulgaria. Campaigns to create ‘fiscal consciousness’ have been successful in India, Israel and Mexico. The introduction of an Independent Authority against Corruption has had major results in Hong Kong.

These measures could not all be easily implemented in our country, but some could serve as useful examples. The study of diaNEOsis arrives at a series of policy recommendations that include:

- a reduction of tax rates and of emergency taxes on already-taxed income;

- expanded use of "plastic money" and expansion of electronic invoicing;

- effective and intensive auditing and effective resolution of tax disputes (through administrative and legal processes);

- improvement of organization and modernization of the tax authorities;

- creation of an electronic tax administration;

- training and education of tax administration employees, along with an increase of their wages;

- tightening of penalties in cases of tax evasion;

- creation of a stable and simplified tax system;

- a gradual change in the structure of the Greek economy;

- creation of tax awareness and cultivation of tax education.

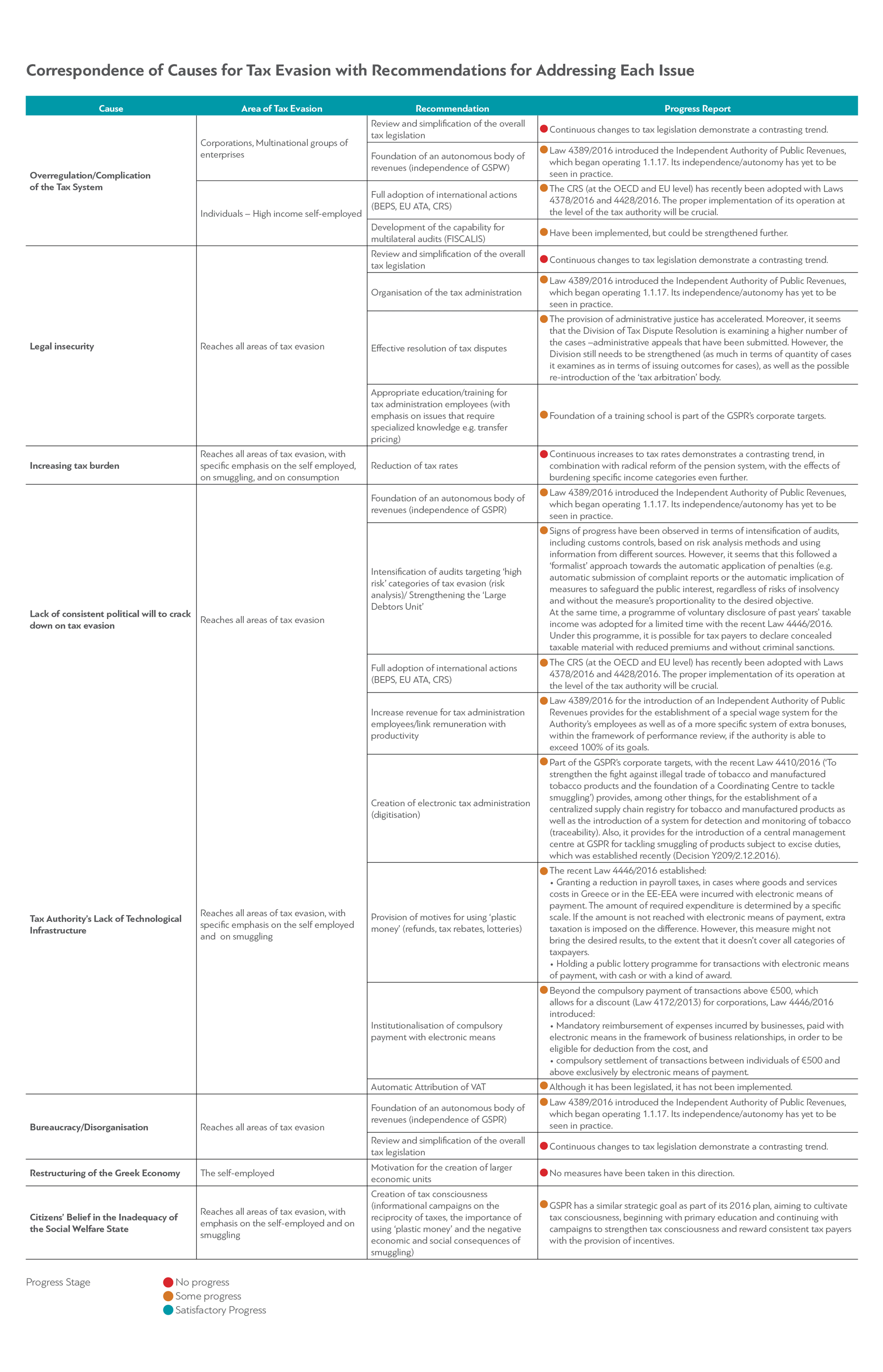

We gathered the various causes of tax evasion, the solutions we recommend and their level of implementation in a convenient table:

The implementation of these recommendations is primarily a political decision. Tax evasion in Greece is a difficult, structural problem of the Greek economy. It has to do with the economy's structure, the high number of self-employed workers, the small average size of companies. Previous political leaders were hesitant to effectively tackle the problem, perpetuating the culture of lawlessness and the justifiable lack of citizens’ confidence in the state.

Today, however, a solution is imperative, and, perhaps for the first time in the country's recent history, possible. Some preliminary steps to strengthen the tax system have already been taken. Hopefully there is room for further steps.

In our study on extreme poverty in Greece, we described a package of measures that could help 1 million Greeks rise above the poverty line. This package has an annual cost of 2.7 billion euros.

Just a 15% reduction in tax evasion would cover that cost.