This survey is not a classic political poll. It attempts to offer a detailed snapshot of dominant views, ideas and values of Greek society today. It brings to light the political and economic views of Greek citizens on the one hand, and, on the other hand, through a number of questions, it maps their opinions about family, interpersonal relationships, immigration, education, religion and human rights. These are views and perceptions that elucidate the current ideological makeup of the Greek society. In addition to measuring classic views and behaviors, the study also paints in broad brushstrokes the picture Greeks have of their own country, and attempts to decipher their opinion on what "being Greek" means to them and explore the existence of any lasting values.

The fact that the survey was conducted at this particular temporal context (in 2015, after SYRIZA’s rise to power, and more than 5 years since Greece began experiencing an unprecedented post-war economic crisis) makes research findings particularly important. However, the survey has been designed as a part of a much broader research strategy (in terms of the type of questionnaire used, the sample size, and the set of issues explored in the focus groups). diaNEOsis intends to conduct this survey annually, in order to track trends and to have more definitive data on the values system of the Greek society over time.

Method

The study consists of one main survey and two follow-up ones:

1. A quantitative survey conducted by pollsters GPO between March 26 – April 24 2015 (excluding the Easter period) with a nationwide representative sample of 2,500 individuals. A sufficiently large sample size was necessary to collect a variety of empirical data. This opinion poll is the main reference survey.

The survey questions covered 5 key topics:

- Europe, the World and National Identity

- Economy, State, Private Sector

- Migration, Minorities, Human Rights

- Institutions, System of Government, Political System

- Education, Culture, Innovation

2. A qualitative study conducted by GPO using focus groups during the period May 26 – June 5 2015 period. The topics for discussion and problems investigated were chosen after the results of the quantitative survey had been analyzed, in order to explore critical issues brought to light by the former survey's results. 4 focus groups were conducted:

- 18-24 age bracket. Key topics discussed: Political and economic views and values.

- Freelance professionals. Key topics discussed: Economic views and values.

- Citizens on low incomes (up to € 500 a month). Key topics discussed: Economic views and values, poverty.

- Those who view racist violence in a positive light. Key topics discussed: Migration, racist violence.

Focus group meetings were held at GPO’s offices and were facilitated by Antonis Papargyris, GPO’s Director of Research (lead coordinator) and by myself.

3. A second quantitative survey conducted by the GPO on November 9-16 2015, with a nationwide representative sample of 1,000 individuals. The objective of the second survey was to explore emerging trends, due to the significant political and economic events that occurred between the March-April 2015 survey (hereinafter the April Survey) and the November 2015 survey. The questionnaire in this second survey was limited compared to that of the main April survey. The second opinion poll contained 19 crucial questions included in the April survey, with the exact same phrasing.

We will discuss the key survey findings below. Emphasis is given on the April 2015 reference survey and on highlighting the minor changes revealed by the November 2015 survey (see section VI).

I. Greece As a Small Country, But a Great Cultural Force

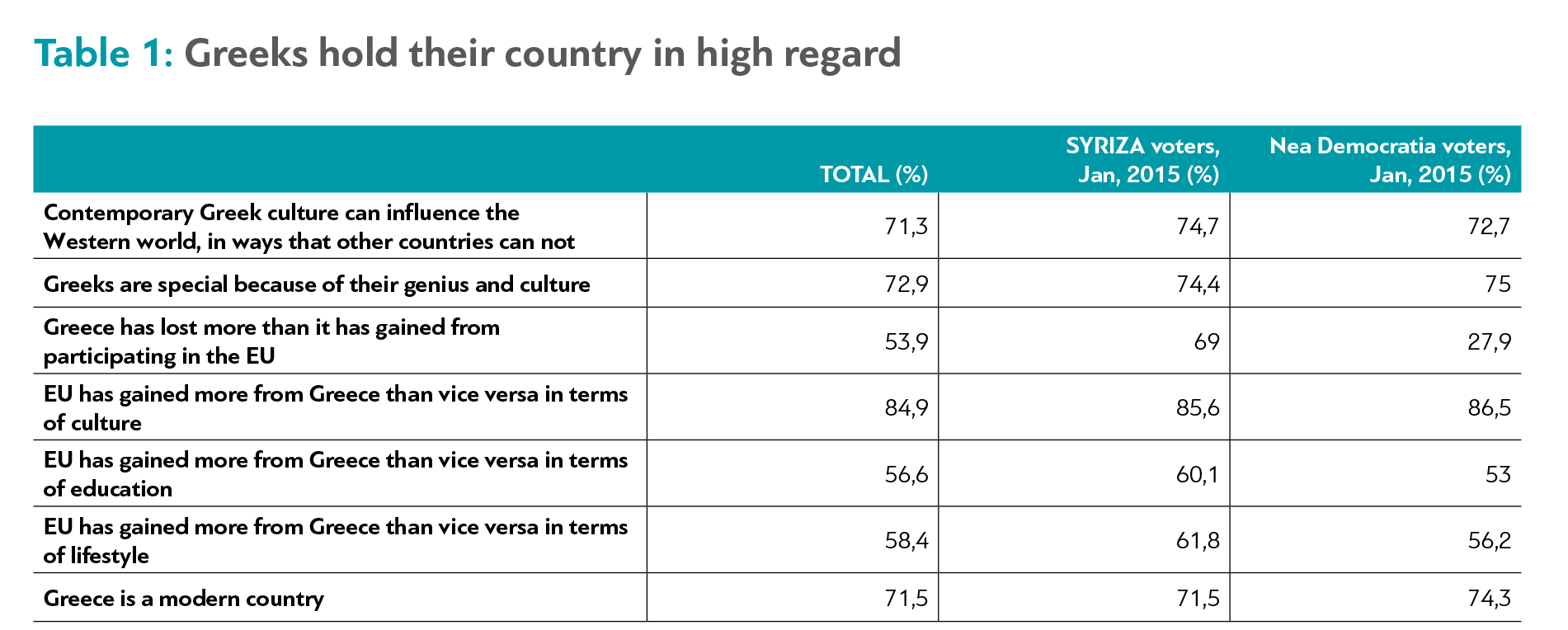

The past is ever present. That’s the first major finding from the April survey. Greeks have always held their country in high regard. A similar survey conducted in 2001 by Kappa Research1, captured the same high regard for the nation, with figures being on a par with those in the current surveys, though somewhat higher (for example in 2001 84.8% of respondents considered that Greece had something important to offer to the West, compared to 71.3% in 2015). The unprecedented economic crisis has only marginally shifted the picture that Greeks have of Greece. Greeks hold their country in high regard, irrespective of their partisan or political affiliation, social class or educational level. The small negative deviations from the median (among men, the highly educated, high income brackets, and young people aged 18-24) are not sufficiently sizeable to affect this core perception.

The past still plays an important role in Modern Greek national identity, especially in matters related to culture, education and lifestyle; it shapes our own image of Greece as a small country, but as a timeless cultural force. These high perceptions regarding the Greek nation appear to have become adapted to modern circumstances, internalized and integrated –as a building block- into the value system of modern-day Greeks. The survey data is clear and doesn’t leave room for assumptions.

Greeks hold their country in high regard

From a different point of view, the fact that the majority believe that Greece is a modern country, despite its particularities and problems (even though there is an average-sized deviation among the young people (aged 18 to 24) and the most highly educated), is also a finding which we consider to be particularly important. This finding constitutes a clear break from the past and the old stereotype of Greece as a poor country far from the European mainstream in a traumatic period.

II. The Weakened -But Still Prevalent- pro-EU Stance, the Rise of an anti-EU Stance.

General Trend

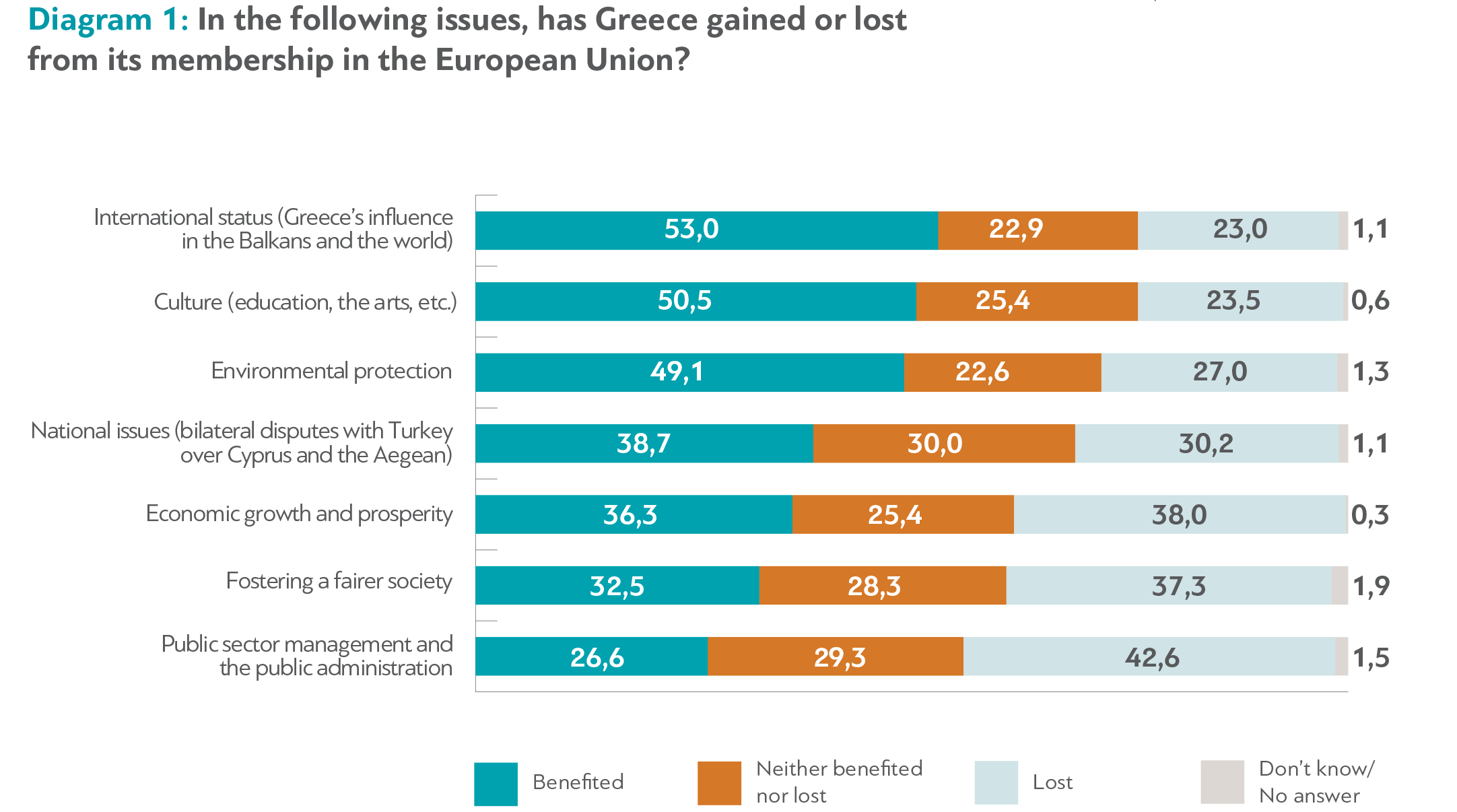

Most Greeks have a positive view of the EU (69%) compared to a significant minority who don’t express particularly warm views. In the past (in the 1990s and 2000s) favorability of the European Union was around the same level2, but the proportion of Greeks who sees their country’s membership of the EU as detrimental was traditionally below 30% (between 22% and 28%). Moreover, the main focus on Greece’s benefits or loses in each policy sector (i.e. if European integration is good for Greece and in what extent) seems to be shifting towards a more negative direction than in the past, even though the balance remains positive3.

Support for the European Union remains strong but cracks in support for Greece’s European future are now visible and significant, as we will discuss later. It is noteworthy that men, older respondents (those aged 55 to 64 and over 65 especially), the most educated, the affluent and people in business are the proportion of the public that holds the highest opinion of Greece’s membership in the European Union; similar trends appear in most EU countries.

1. The pro- EU camp, as a cohesive group

Support for the European Union remains strong but cracks in support for Greece’s European future are now visible.

Based on all answers provided, we consider that those who said that they were clearly in favor of the EU comprise the main and fundamentally central camp that clearly supports Greece’s European identity. This assumption proved to be correct, in light of the events that followed.

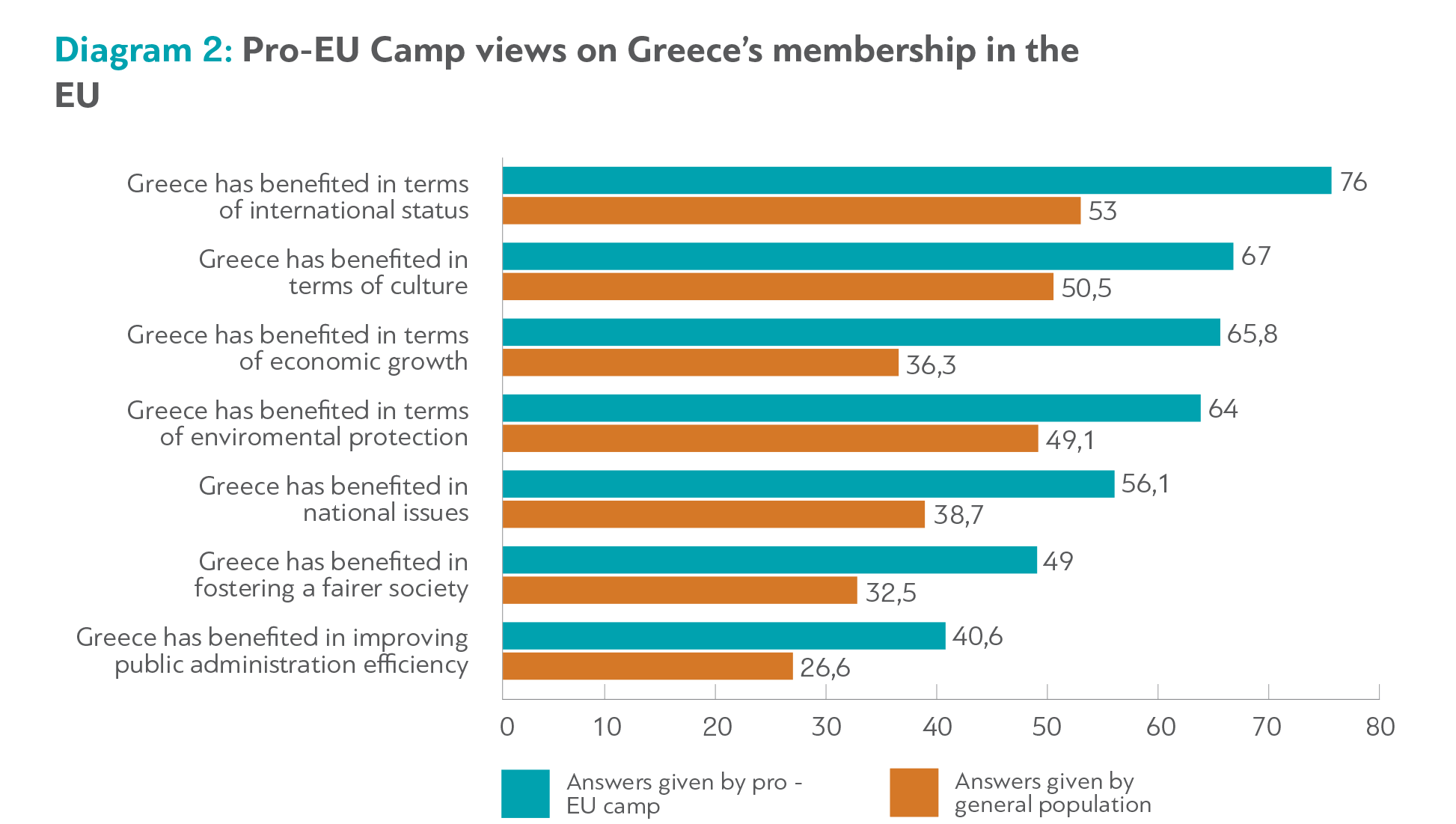

So we believe that around 40% of the population make up the main camp of pro-Europeanism in Greece. This pro EU-camp in effect operates as the main pillar of Europeanism: It is (a) narrower than the segment of the population that provides wider (but scattered and strongly conflicting) support for the country’s European prospects and (b) wider than what we will call "hardcore Europeanism". Diagram 2 shows the views of EU supporters compared to the corresponding views held by the general public concerning Greece’s membership of the EU.

The figures suggest that Greek EU supporters think that the country has benefited from participating in the EU on all policy sectors. The numbers are systematically -and significantly- higher than the numbers for the general population. Moreover, this group considers that Greece has benefited from its EU membership (57%, compared to the exceptionally low figure of 32.5% for the general population), setting itself apart from the negative views in the general population.

Data not included in Diagram 2 suggest that that 93.9% of respondents believe that Greece should stay in the Eurozone (compared to 73.9% of the general population) and 67.8% think that "EU countries did help Greece in overcoming the debt crisis" (compared to just 42.5% of the total sample). It also comes as no surprise the fact that EU supporters are the segment of the population most favorably disposed towards globalization, believing that "Globalization is an opportunity for Greece" (52.4% compared to 36.5%).

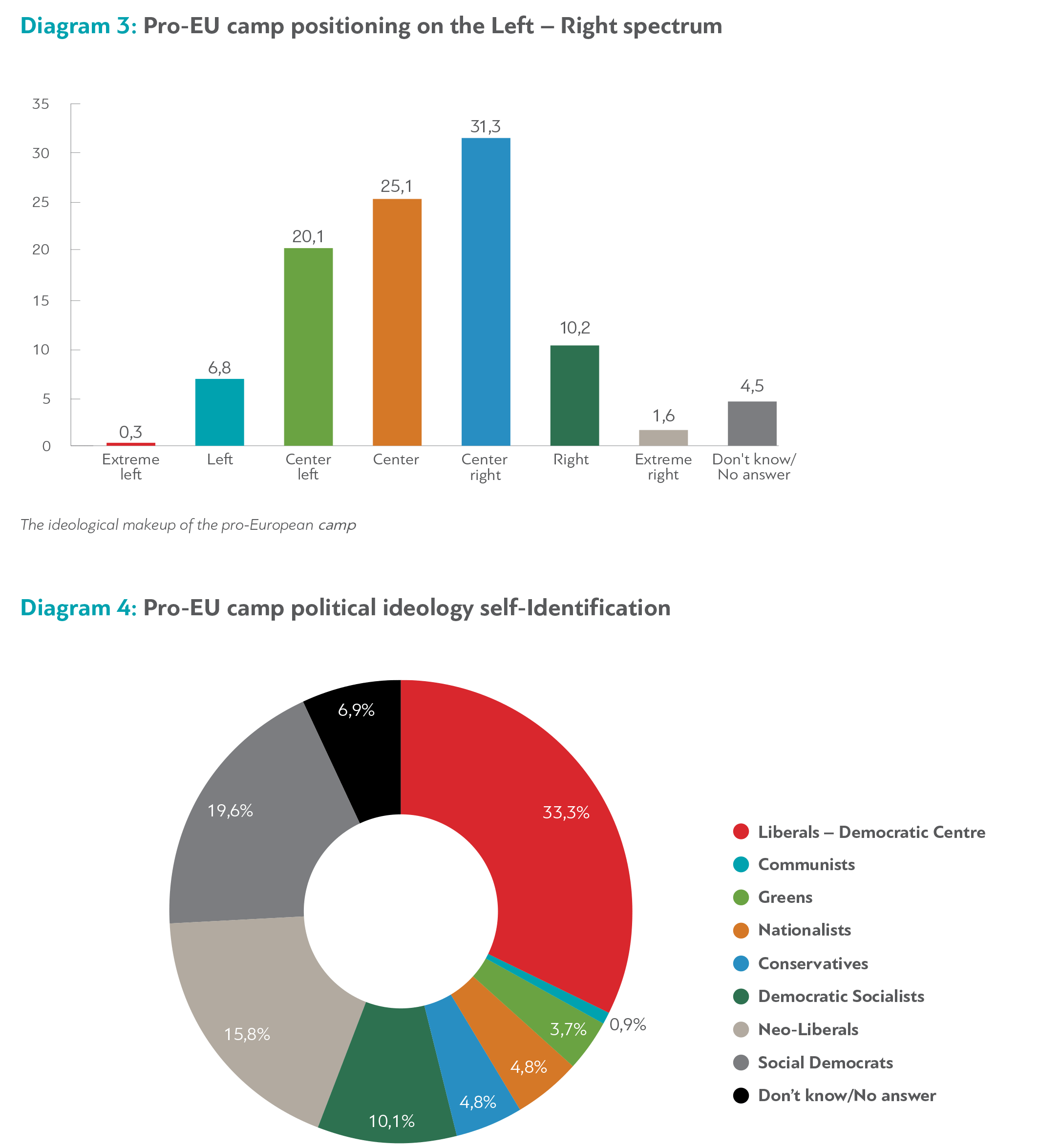

The data demonstrate the cohesiveness of pro-European preferences by this segment of the population. Politically and ideologically speaking, Greek EU supporters lie midway along the Left-Right spectrum (center-right, center and center-left, see Diagram 3). Moreover, when asked about how they would identify themselves in terms of ideology positioning, 33.3% identify themselves as Liberals – Democratic center, 19.6% as Social Democrat, 15.8% as Neo-liberal and 10.1% as Democratic Socialist (Diagram 4). Consequently, Greek EU supporters tend towards moderation and political pragmatism. Nonetheless, a significant proportion of those in the pro-European camp have more robust, less ‘centrist’ political views (such as the Neo-Liberals and the Democratic Socialists), which indicates the complex, diverse nature of this group.

Greek EU supporters made a very clear choice to support EU membership, but they don’t actually believe in the European dream.

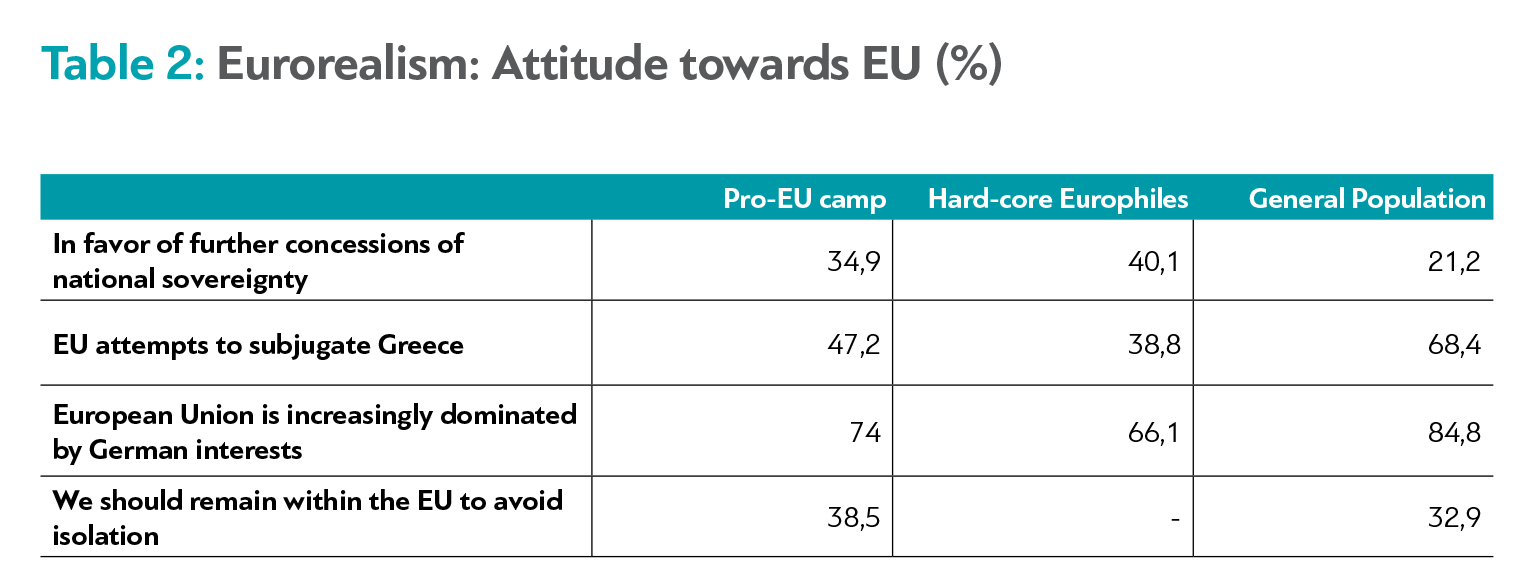

Consequently, this group's pro-Europeanism cannot be understood outside the context of realism, which is its distinguishing characteristic. While only 2.2% of EU supporters (compared to 17.2% of the general population) consider that EU institutions "represent interests that don’t serve Greece’s strategic plans", at the same time just 33.5% reply that "it is vital for Greece to remain within the EU" (compared to 17.8% of the survey sample). Moreover, just 34.9% of this group (compared to 21.3% of the general population) agrees with the prospect of "conceding a significant portion of our national sovereignty to the EU, towards a politically united Europe", and 47.2% (compared to 68.4% of the general population) consider that "during the recent crisis, Eurozone countries attempted to subjugate Greece".

Many of the figures point in the same direction: Greek EU supporters made a very clear choice to support EU membership, but they don’t actually believe in the European dream. EU supporters in Greece are primarily "realists".

2. Two Hardcore Camps: The Pro-EU Camp and the Emerging Anti-EU camp

2.1. The hardcore pro-EU camp

If the percentage of Greek EU-supporters is around 40% of the population, the hardcore Greek Europhiles are estimated at around 17% to 20%4.

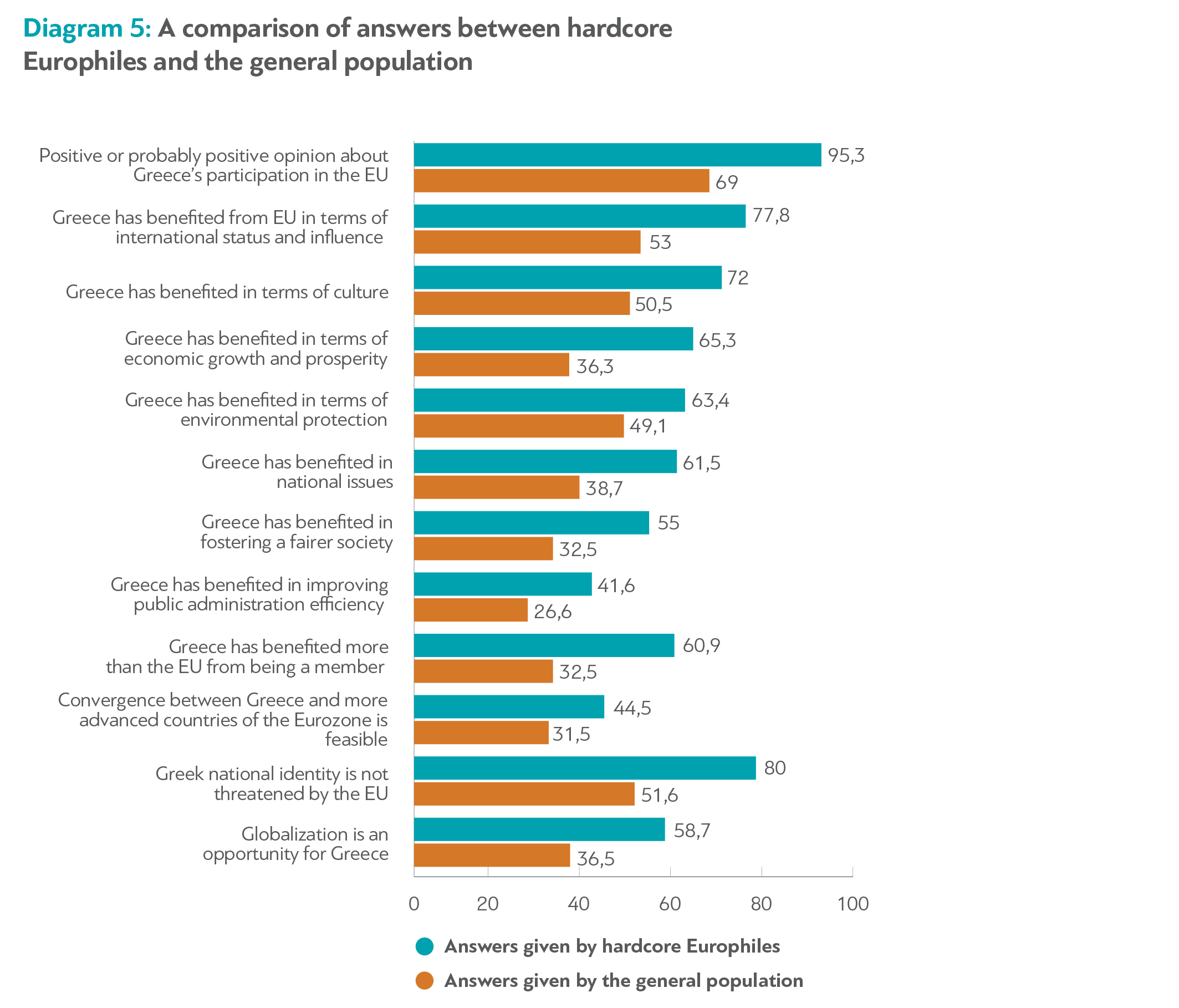

These citizens have a favorable view of the European Union and believe that Greece has benefited from being a member of the EU (see Diagram 5). The pro-European stance of this group is systematically greater compared to the stance of the "regular" pro-EU camp. For example 60.9% consider that Greece benefited comparatively more than the EU from being a member of the EU (the figure for the general population is 32.5% and for the pro-EU camp is 57%) and 44.5% believe that the objective of convergence between Greece and the more advanced countries of the Eurozone is feasible (compared to 31.5% of the general population and 41.5% of the pro-EU camp). Moreover, an impressively high 80% believe that EU doesn’t threaten our national identity (compared to 51.6% of the overall survey sample and 73% for the pro-EU camp) and 58.7% see globalization as an "opportunity for Greece" (whereas the sample average was 36.5% and for the pro-EU camp the average was 52.4%). It is noteworthy that, when participants were asked that if "instead of being a member of the Eurozone, Greece’s interests might be better served by developing a special relationship with another country", 71.1% of hardcore Europhiles disagreed (the respective figure for the whole sample of the survey was 47.4% and for the pro-EU camp was 61%).

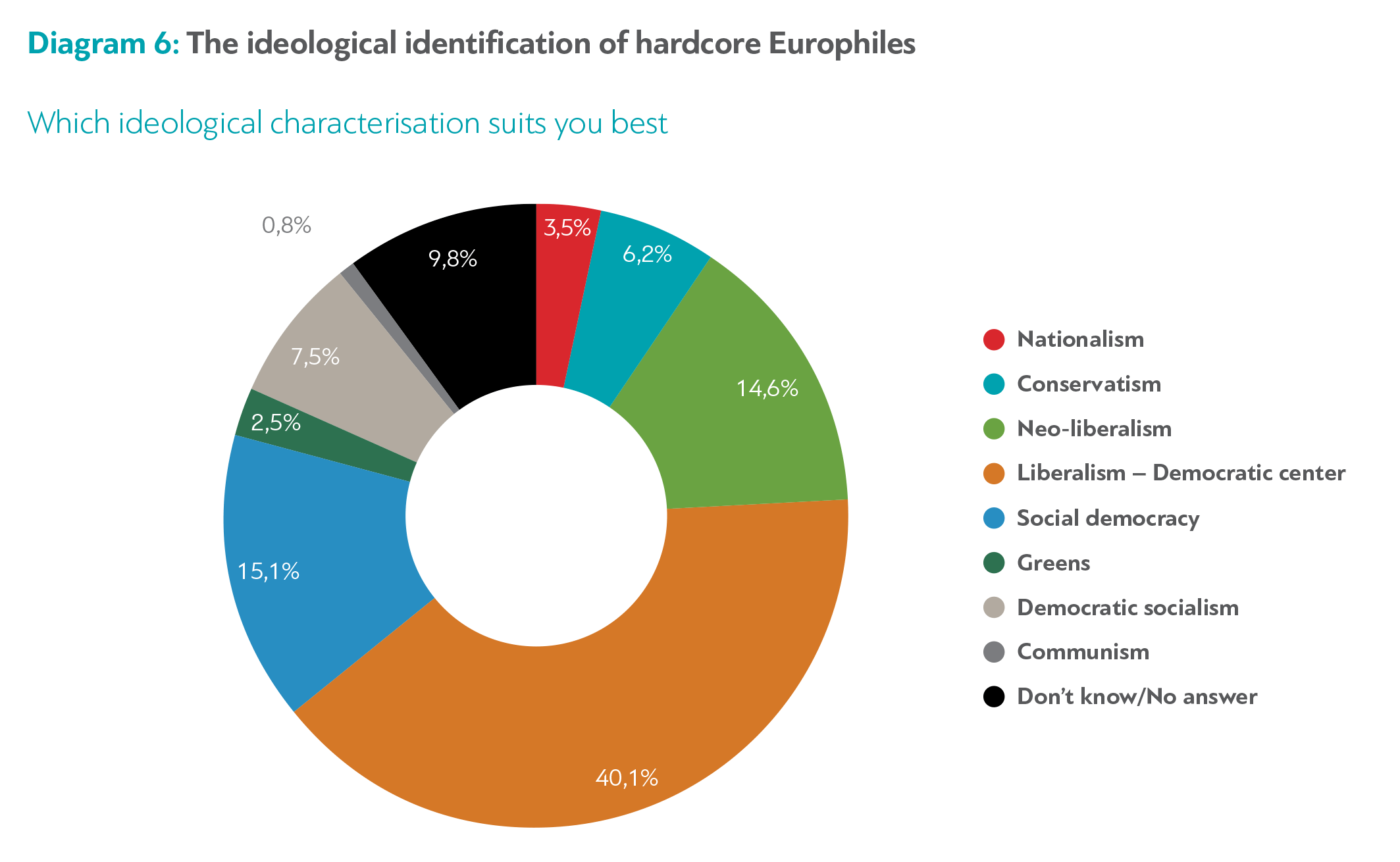

The main ideological focus of hardcore Europhiles, compared to the pro-EU camp, is shifting towards the center of the left–right ideological spectrum, but also includes a significant percentage of citizens who either identify themselves as social democrats or Neo-liberals (Diagram 6).

However, these demonstrably more enthusiastic advocates of the European Union show a more realistic approach to the current phase of European integration. Only 41.1% (compared to 34.9% of the pro-EU camp and just 21.3% of the general population) wish to "concede a significant portion of national sovereignty to the EU towards a politically united Europe". The opinion that "during the recent crisis Eurozone countries attempted to subjugate Greece" is illustrated by 38.8% (compared to 47.2% for the pro-EU camp and 68.4% of the general). Moreover, the view that "European Union is increasingly dominated by German interests" was supported by the majority (66.1%), as was the case with the pro-EU camp (74%) and the general population (84.8%). (Table 2)

In conclusion, it appears that the general Greek pro-EU camp consists of around 40% of the overall population, while the hardcore Europhiles within that wider group, accounts for less than 20% of the overall population. Nonetheless, there is no significant qualitative difference between hardcore Europhiles and the wider pro-EU camp. There is a difference in the degree of "Europeanism", but not in qualitative characteristics. Although significant, this difference cannot be considered determinative. For this population group, Europe is a more decisive, and less controversial political choice.

2.2. The Hardcore Eurosceptics

If the hardcore Europhiles are around 17% to 20% of the population, the figure for the hardcore Eurosceptics seems to be around the same5. However, this core appears to be more cohesive in terms of its anti-European preferences compared to the pro-European group.

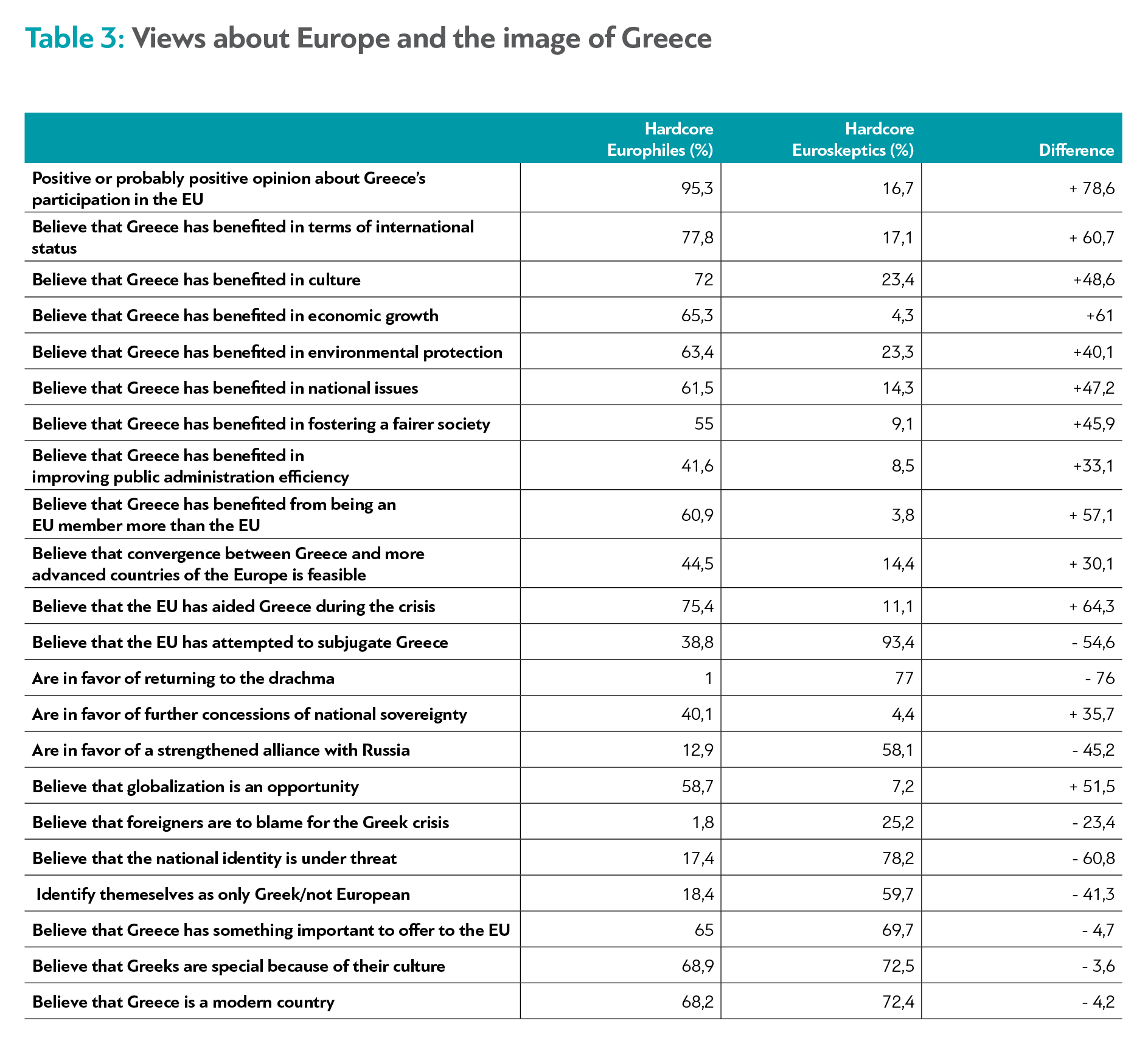

The data in Table 3 speak volumes.

The percentage of hardcore Europhiles are around the same with the one of hardcore of Eurosceptics.

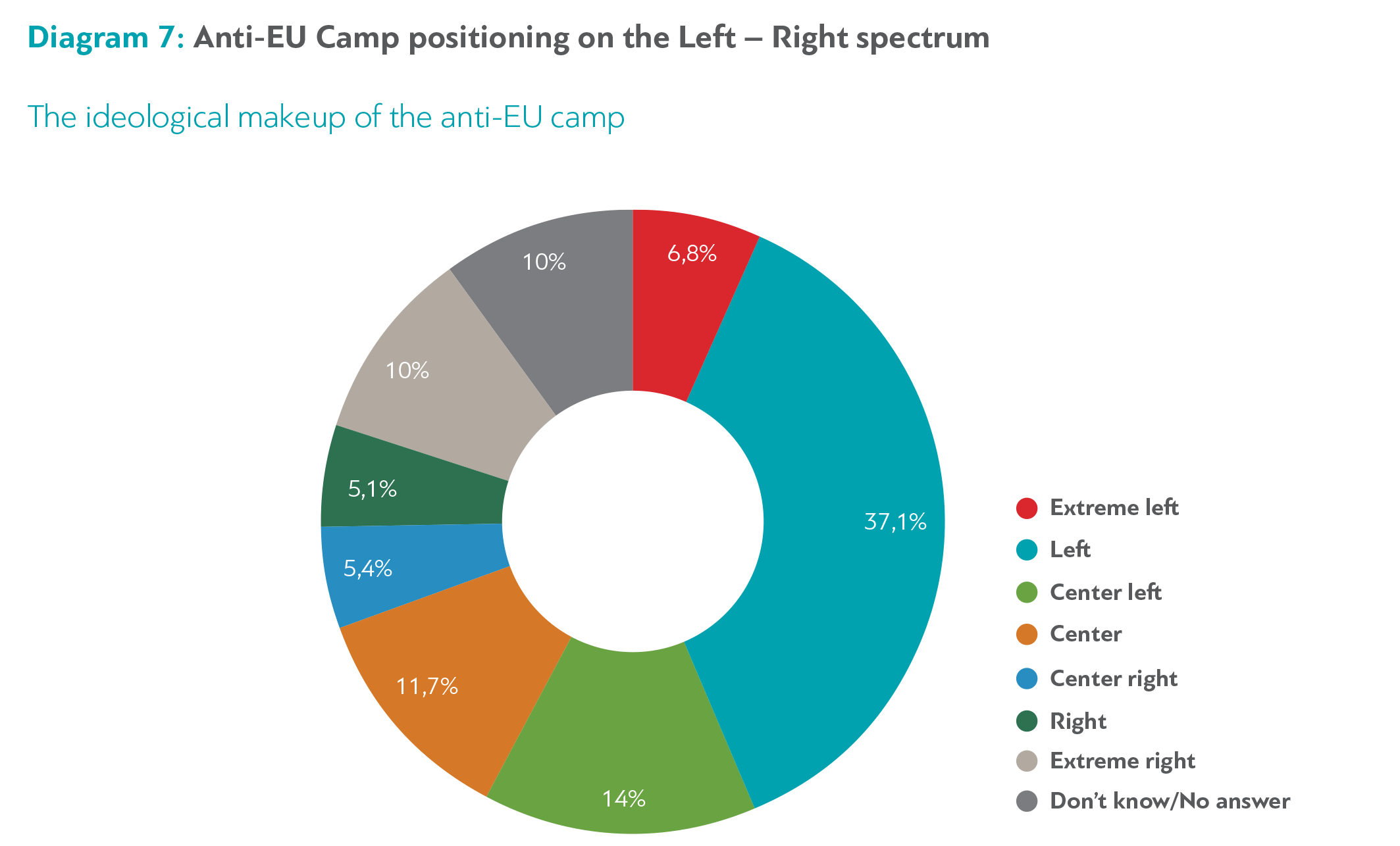

The political- ideological composition of hardcore of Eurosceptics is exceptionally interesting; leftists (37%), the far-right (10%) and far-left (7%), center leftists (14%) and centrists (12%) (Diagram 7). In some ironic sense, both Europhiles and Eurosceptics believe that Greece is a unique country (Table 3). Opposing ideological camps hold Greece in equal high regard.

In conclusion, Greece’s European future and the EU itself are rejected by 17.2% of the Greek population, in a surprisingly systematic manner. The rejection is decisive and, above all, cohesive because it has been expressed in a repeated, cumulative manner through a large number of findings that complement each other (matching sets of responses); it extends to all aspects of Greece’s relationship with the EU. It is more pronounced in the economic and social aspects of the relationship, but (to a slightly lesser extent) it touches without exception all aspects of public policy, even culture: The EU "threatens" our national identity, "harms" our culture (education, the arts, and so on), and on the other hand the EU has benefited from Greece in terms of culture, education, and lifestyle.

For hardcore Eurosceptics, there is an unequal balance of exchange between Greece and EU: Europe has benefited from Greece, while Greece has paid a high cost.

Summary

1. In the 1990s and partially in the 2000s Greece was a markedly pro-EU country (Christoforos Vernardakis). That picture now belongs to the past. Greece, a country that was at the forefront of Europeanism, is now bringing up the rear The pro-Europeanism of both hardcore Europhiles and the wider pro-EU camp is stable and deeply-ingrained, but federalism is more than ever a minority view; eurorealism is now the heart of Greek pro-Europeanism.

2. The main pillar of support for Greece’s European prospects comes from around 40% of the population. This group has a relatively coherent pro-European identity, it believes that Greece has benefited from being a member of the European Union, but it also has mixed views about the European project and does not embrace –with the exception of a hardcore minority- the "European dream".

3. The consolidation of a group that is not just Eurosceptic but actually anti-EU (consisting of 17%-20% of the population according to the April 2015 survey, but appeared to be larger according to the November 2015 survey) is a new factor in Greek political life and one of the most important findings of this survey.

ΙΙΙ. Between Neo-liberalism and Social Democracy: A Mixed Economic Culture Subtly Dominated by Neo-liberalism

General trend

On economic issues, diaNEOsis’ survey confirms the steady weakening of state-centric viewpoints (which has been going on from at least the 1990s) and the rise of standards and values closer to neo-liberalism. Of course, these state-centric views were never extreme, but moderate and part of a balanced economic culture which combined neo-liberal values with more social democratic ones. This mixed economic culture tended more towards economic liberalism, free of the latter’s momentum domination or hegemony.

The fact that 68.9% of respondents believe that the economic crisis has occurred because of the weaknesses of the Greek political economy and just 10.2% lays the blame on foreigners, is considered to be a ground-breaking finding.

The majority of population is positively disposed towards privatization and also agrees with the establishment of private universities

As far as the state’s role is concerned, 53.8% of the overall sample consider that the state "has always interfered excessively" in the way markets operate, compared to 42.4% who hold the opposite view. This majority view is also held by an impressive portion of SYRIZA’s voters (42%). A large majority (67.2%) also believe that abolishing permanent tenure for civil servants would "improve public sector management" (the percentage for SYRIZA voters is 56%), while 86% approve foreign investment in Greece and 71.5% would approve foreign investment in strategic sectors of the Greek economy, while 58.4% of the sample disagree with the view that "foreign investment encroaches on national sovereignty" while 52.2% disagree with the view that "foreign investment doesn’t respect employee rights".

The majority of the population (56.7%) is positively disposed towards privatization of state-owned businesses and also agrees with the establishment of privately owned universities (57.7%). Moreover, concepts closely associated with capitalism such as "competitiveness" (86.7%), "markets" (66.6%), and "market economy" (64.9%) are much more acceptable than the core concept of capitalism itself (23.9%)

57.5% of population believe that public sector needs improvements

The wide acceptance of liberal economic ideas does not ipso facto mean that Greeks have become neo-liberals. Greeks still distrust concepts such as capitalism (viewed positively by only 23.9%), the stock exchange (viewed positively by only 35%)6, and multinational enterprises (viewed positively by only 38.1%). Negative views about privatizing public utilities and services (with 51.6% against and 45.6% in favor), trust in public education (58.5%) compared to private education (41.2%) and the preference towards an economic model, with "high taxation and a robust welfare state", (49.7% of the sample) compared to a model with "low taxation and less comprehensive welfare system" (39.2%) point towards the same direction7. Also, 57.5% of respondents believe that the public sector should improve without growing or shrinking in size, while 36.4% believe that public sector performance could be improved with a smaller, better organized public administration and only 5.6% believe that this could be achieved with a larger public sector.

Left-right, Europhiles and Eurosceptics: How economic preferences shape up

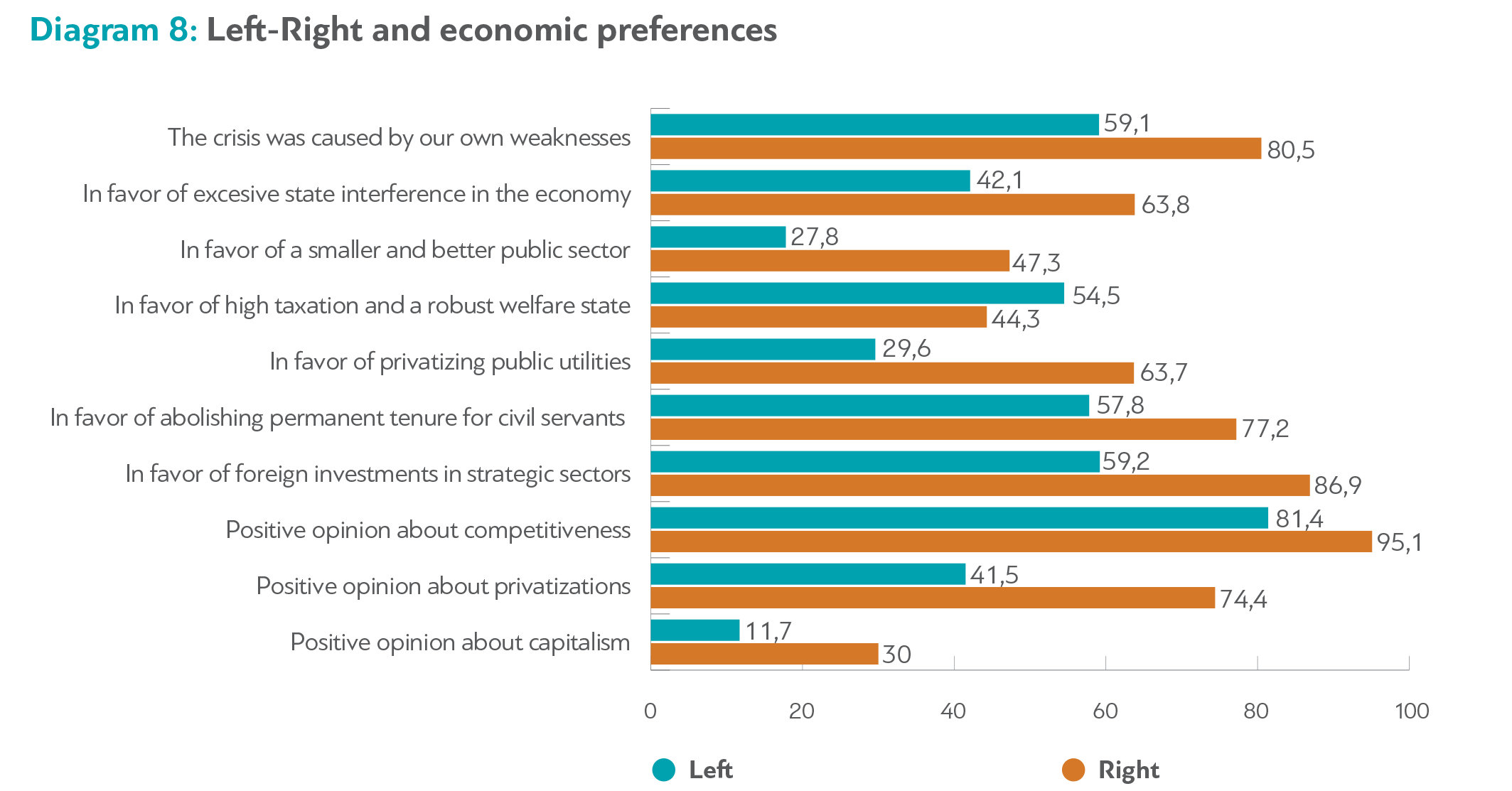

We can further examine the matter based on how respondents identify themselves on the Left-Right spectrum. The ‘Left’ group includes all those who identify themselves as belonging to the extreme left, left and center left, while the ‘Right’ group comprises of all those self-identified as center-right, right and extreme right. Respondents self-identified as belonging to the center are not included in these two groups (or in the analysis).

The figures in Diagram 8 leave no room for doubt. The Left-Right spectrum is systematically associated with different viewpoints on economic matters. The argument that the Left-Right divide has lost its force is not supported by the data.

However, save for the important exception of the privatization of public utilities (and to a lesser extent the related issues of foreign investment in strategic sectors of the economy and the positive or negative views on privatizations in general) the survey does not reveal any deep divide associated with how citizens identify themselves in political-ideological terms. On economic matters, there aren’t two "values" camps, which run into head-on conflict. To a significant degree both have adopted ideological themes that come from the Left. The Left-Right dichotomy is divisive, however, it doesn’t generate an across-the-board, deep-seated divisive picture of the economic preferences of Greek citizens.

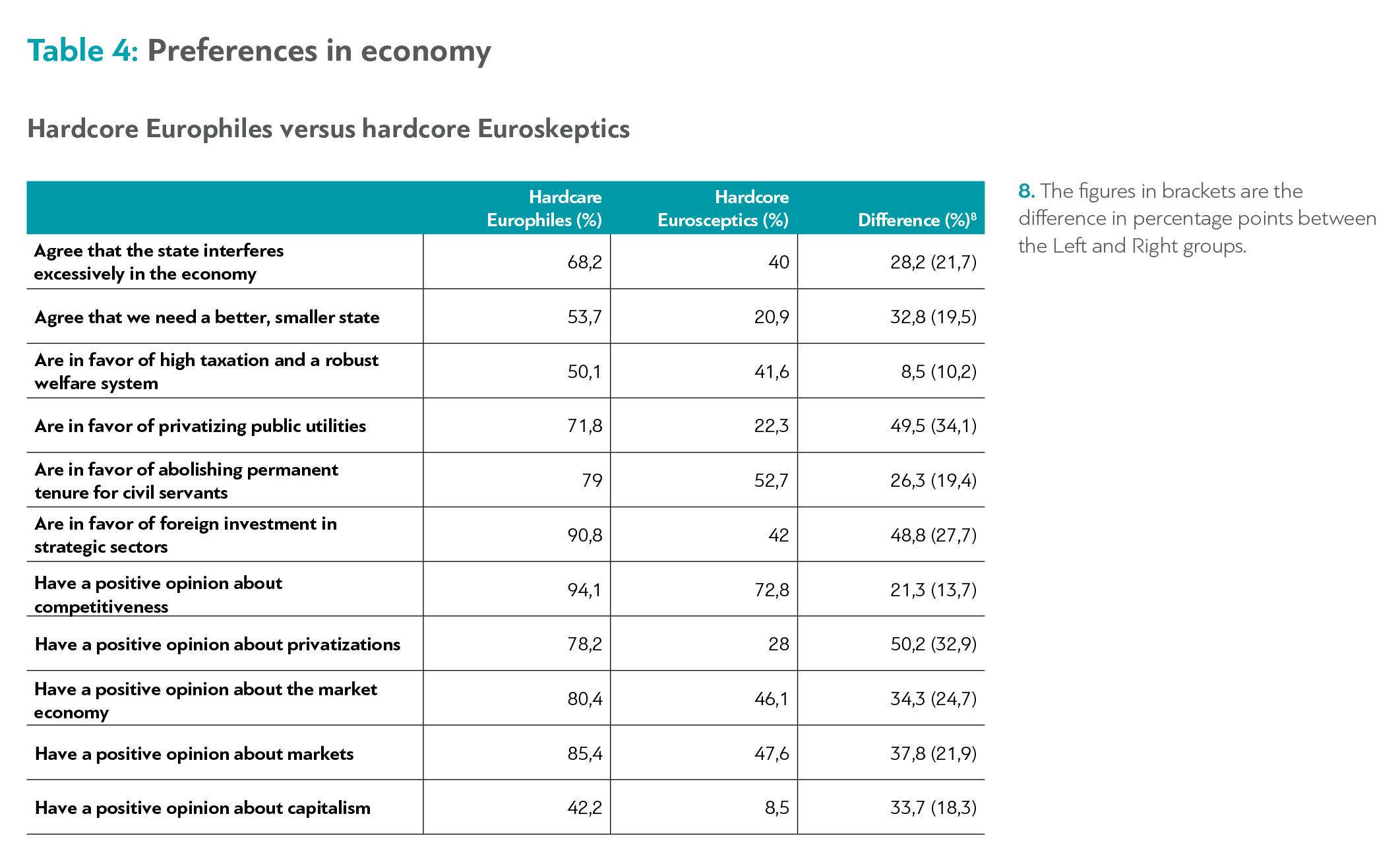

Strangely –or, perhaps, not strangely at all- economic values and preferences of the group we called "hardcore Europhiles" and the one we named as "hardcore Eurosceptics" (see above) are further apart with those of the "Left" and "Right", as you can see in Table 4.

The deviation in economic preferences is systematically higher (with the sole exception of the response to the question of whether they stand for ‘high taxation and a robust welfare state’) between those in hardcore Europhile and hardcore Eurosceptic groups, compared to the deviation between those in "Left" and "Right" groups. It appears that the European dividing line is also shaping the views of respondents on economic issues, as it does in the topic of "Europe" itself. Since the Left-Right divide has historically focused around the economy, the fact that another divisive issue correlates better with the differences in economic views held by citizens is definitely a finding of great importance. There are two reasons for this: Firstly, because it confirms that the Left-Right divide has lost part of its divisive power even over the central issue of the economy, where one would expect it to be stronger, and secondly precisely because the hardcore pro-European and hardcore Eurosceptic dilemma seems to have expanded its own divisive power that now goes beyond the narrow confines of European issues. It now has a more powerful role to play in political and ideological conflicts than in the past. The 5-year long conflict between pro- and anti-MoU supporters and viewpoints has clearly had an impact here.

Summary

1. Our findings confirm that economic liberalism leads in the context of a balanced economic culture which has integrated many social democratic elements. The major economic crisis of 2010-2015 did not reverse the trends identified in previous decades and did not lead to major changes either towards liberalism or towards social democracy. Voter radicalization in politics has not been accompanied by a similar radicalization in economic issues. This important trend appears at a time when EU-imposed austerity policies had been largely disavowed by the majority (just a few months after the rise to power of the radical left party). This deviation stresses the relative autonomy of the political sphere and the relative ideological stability of Greek society.

2. Greeks appear to be steadfast in their opinions about the economy, with the emergence of ‘Europe’ as an important parameter in realigning preferences and differences. We do not predict that the increased importance of the "European" dividing line will turn out to be ephemeral. Due to the painful experience of austerity policies, this new division came about violently, although with some delay compared to other countries. It is, however, here to stay.

IV. Cultural liberalism vs. Cultural conservatism

General trend

Attitudes of respondents on immigration have been systematically negative in Greece. 94.5% of those interviewed agree or probably agree that the number of immigrants in Greece over the last decade is excessively high. 74.9% also agree that high levels of immigration increase crime levels and 69.8% believe that it also increases unemployment levels, while 63.6% disagree with the view that immigration can cause positive effects on the economy, or that immigration enriches our culture (70.2%) or even that immigration could improve Greece’s precarious demographic situation (74.5%)9. An important disclaimer: These results came before the Syrian refugee crisis. That even peaked in early 2016, and was examined in a separate diaNEOsis study.

94.5% of Greeks agree or probably agree that the number of immigrants in Greece over the last decade is excessively high.

The attitude of Greek citizens towards the plan to establish an official mosque in Athens is interesting. 58.6% said that they agree, but that figure drops slightly to 54.4% when they are asked if they agree with the construction of a Muslim place of worship in an area close to their residence10. Moreover, 75.2% said that they agree that children of immigrants born in Greece deserve the right to become Greek citizens.

Greeks appear to be divided when they are asked if they agree with the potential to bring back the death penalty (51.2% compared to 48.2%). Moreover, a significant majority of Greeks (59%) agree with the introduction of a civil partnership scheme for same-sex couples. On the other hand, the majority disapproves gay marriage (59.5% are against it). Negative views are also dominant on the issue of legalizing soft drugs (69.1%).

These findings indicate (at least as experience from Europe and the USA shows) a divisive line between "libertarian" and "authoritarian" values, according to Anglo-Saxon approaches or between "cultural liberalism" and "cultural conservatism", to use terms well-established in French political sociology. This divisive line is clear, and rather active within Greek society.

Left – Right and preferences along the cultural liberalism and conservatism spectrum

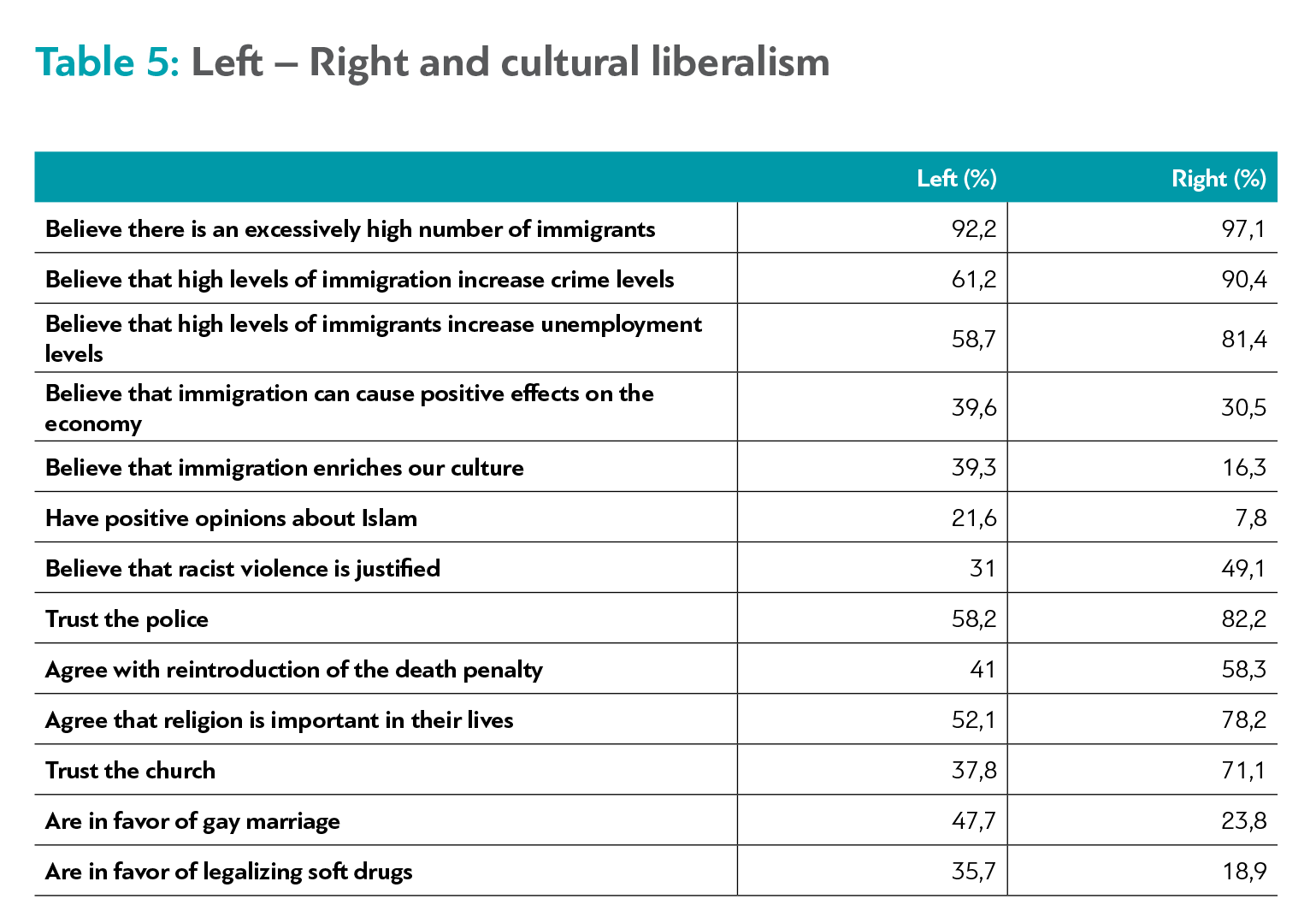

Exploring these issues by asking respondents to identify themselves along the Left-Right spectrum (with the "Left" group including all those who identified themselves as belonging to the extreme left, left and center left, and the "Right" group comprising those who identify themselves as center right, right and extreme right) shows that there is a systematic difference in preferences (Table 5).

However, even though the "Left" group systemically adopts views more oriented to cultural liberalism than the "Right" group, the differences don’t seem to be particularly significant. In the majority of topics included in Table 5, the Left appears either to have adopted views more oriented to cultural conservatism (particularly on immigrant issues) or to be divided between liberalism and conservatism. Only when it comes to issues like racist violence, the death penalty, and distrust in the church (and -in part- on the issue of gay marriage) we can argue that the "Left" group can be considered as culturally liberal in a more decisive manner. On the contrary, the majority of the 'Right' group is clearly culturally conservative. Both these conclusions allow us to argue that Greek society is culturally conservative.

In addition -and this is exceptionally interesting- the values and preferences of the group we named "hardcore Europhiles" and the group we named as "hardcore Eurosceptics" converge significantly on issues of cultural liberalism/conservatism. The differences are minor and non-systematic. The European divide extends beyond questions of 'Europe' into economic issues but it appears that it has not affected preferences associated with cultural liberalism or conservatism.

Summary

1. On questions relating to immigrants, negative opinions were decidedly dominant. The dominance is somewhat ameliorated if we take into account that the majority of respondents (75.2%) agree with Greece-born children of immigrants' right to citizenship, the expansion of a civil partnership unions to include same-sex couples and plans to establish mosques in Greece.

2. Overall, Greek society is culturally conservative, with highly conservative and authoritarian views at the right and extreme right edge of the political spectrum.

3. Self-identification along the left-right spectrum determines significantly, but not decisively, respondent’s preferences. If we accept that the three right-wing positions on the spectrum correlate to culturally conservative preferences, we also accept that the respective three left-wing positions correlate only in part to culturally liberal or ‘progressive’ preferences. This partial asymmetry indicates a mixed culture, just as it does with preferences in economy, but we can argue that conservatism is an important component of Greek ideology.

V. Institutions, System of Government, Political System

General trend

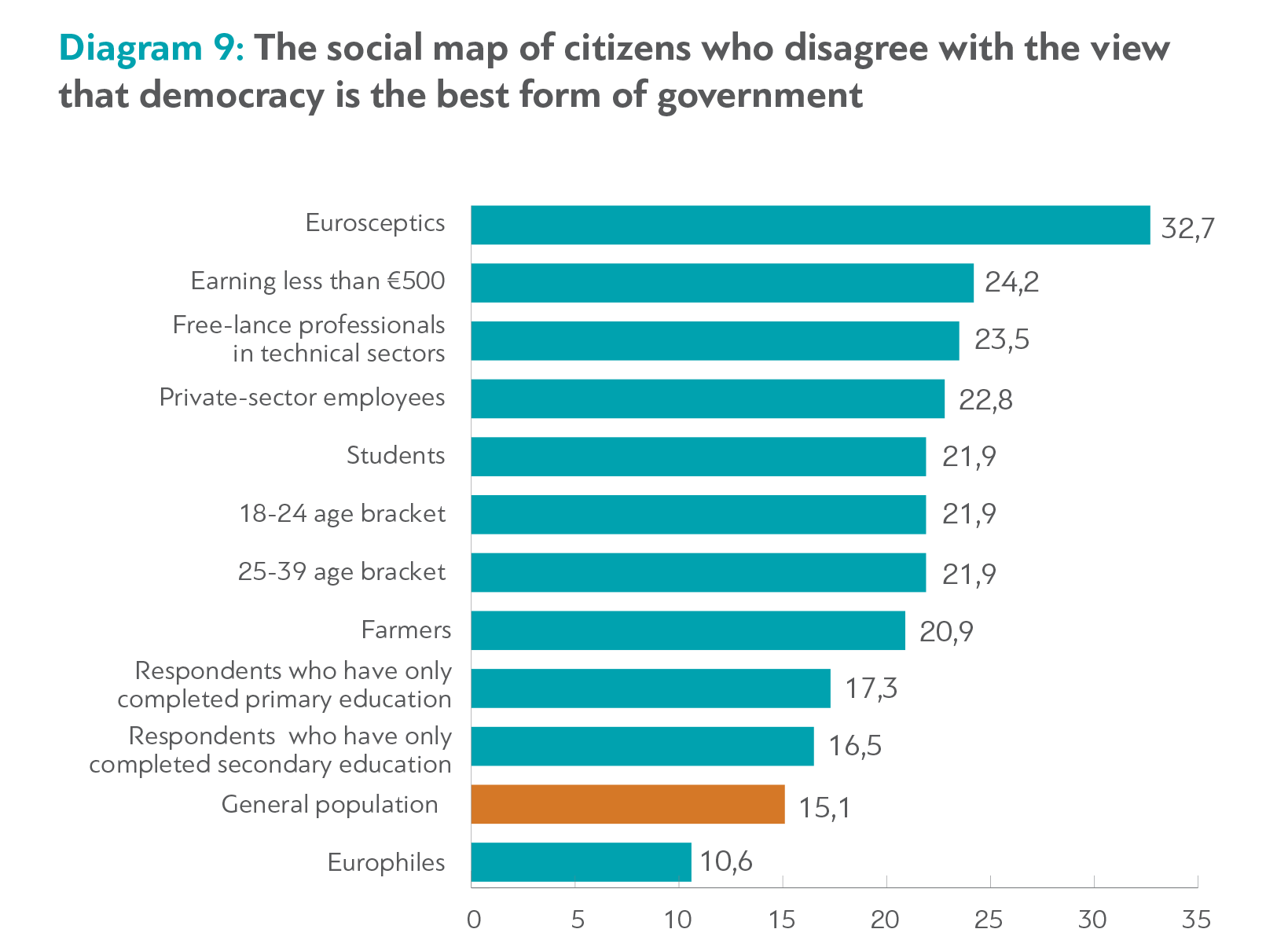

The great majority of citizens (83.8%) agree that democracy is the best form of government. There is, though, a small but not negligible minority of around 15.1% with a different opinion and we believe that it is extremely interesting to look carefully into that specific segment of the population (Diagram 9).

Although parliamentary democracy traditionally enjoys widespread acceptance, the institutional environment which constitutes the essence of parliamentarism is, to a large extent, viewed negatively. With the exception of positive responses to questions about political freedom, Greek citizens responded negatively to issues related to the protection of the rights of minorities and on the right to equality before the law. The most negative views are related to the judicial system (only 27.8% believe that the court system treats all citizens equally) and meritocracy (only 23.2% believe that "competent people gain acknowledgment and rewards".

Greek citizens responded negatively to issues related to the protection of the rights of minorities

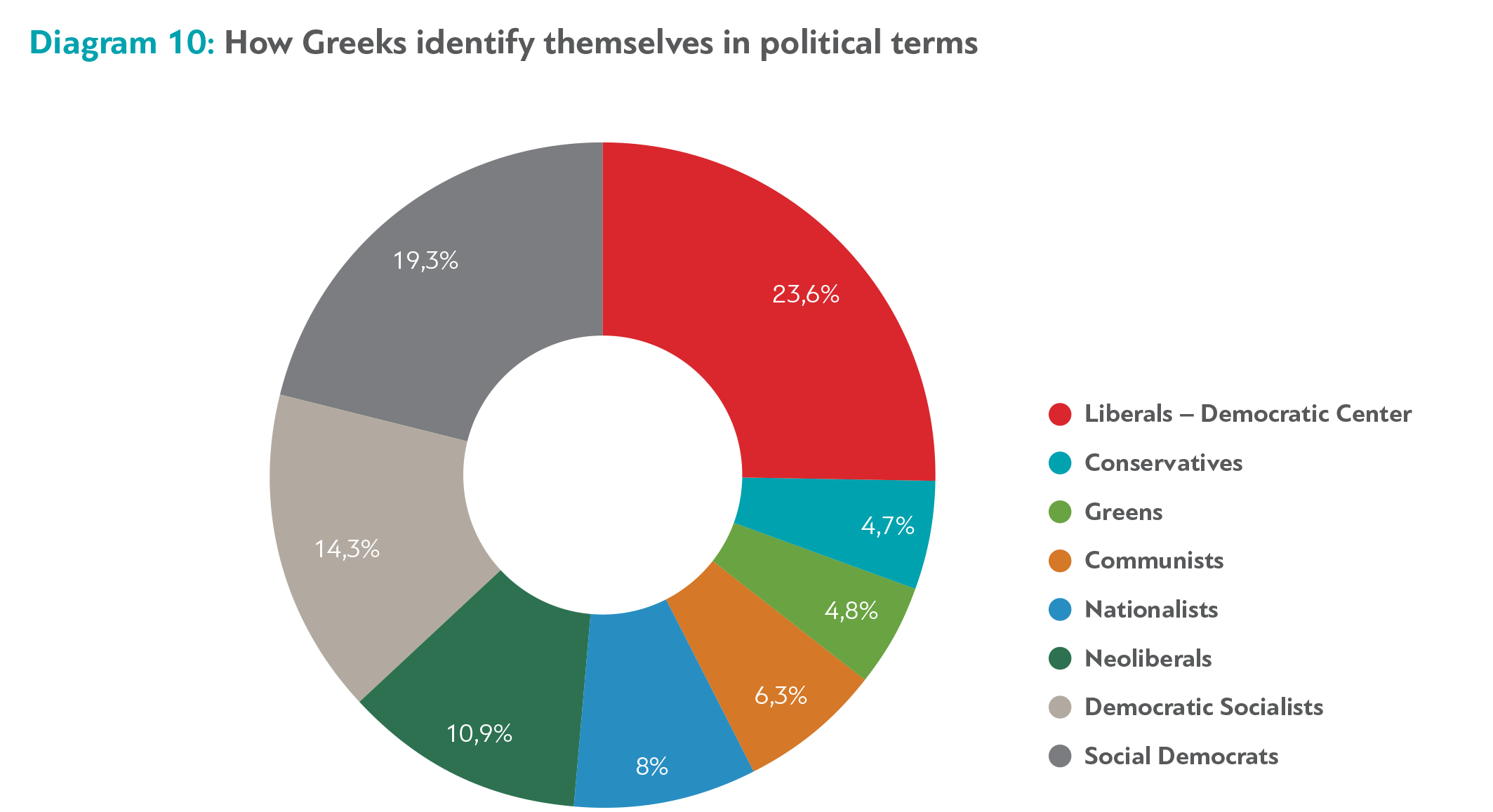

According to respondents the major problems modern Greek democracy faces are corruption/vested interests (51.3%) and the partisan/clientelistic state (24.2%). Citizens rank NGOs (28.7%), employers associations (18.9%), political parties (18.1%), trade unions (17.2%) and Greek media (15%) rather low on the scale of trust. Given the fact that the survey was conducted during the first few months of SYRIZA rise to power, it is interesting that the ideological characterization or identities chosen by Greek citizens reflect the dominant political orientations associated with moderate policies

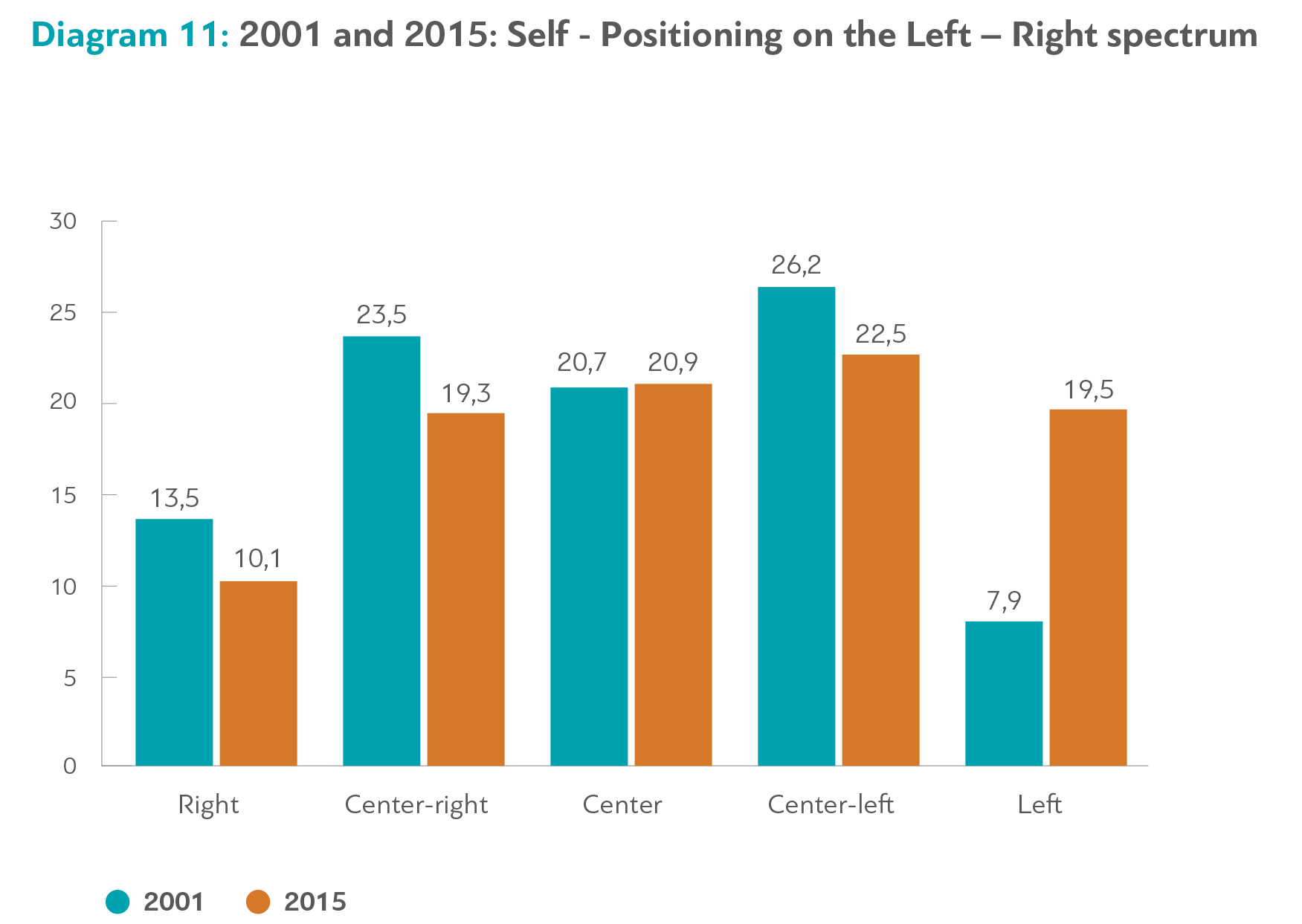

Moreover, when participants were asked to place themselves on the Left – Right spectrum we show that there is a traditionally large concentration of voters in the middle position of the spectrum, with exceptionally low figures for those who identified themselves as right-wing extremists or left-wing extremists. Diagram 11 depicts self-positioning and compares the recent data to the respective data from 2001 (Kapa Research survey).

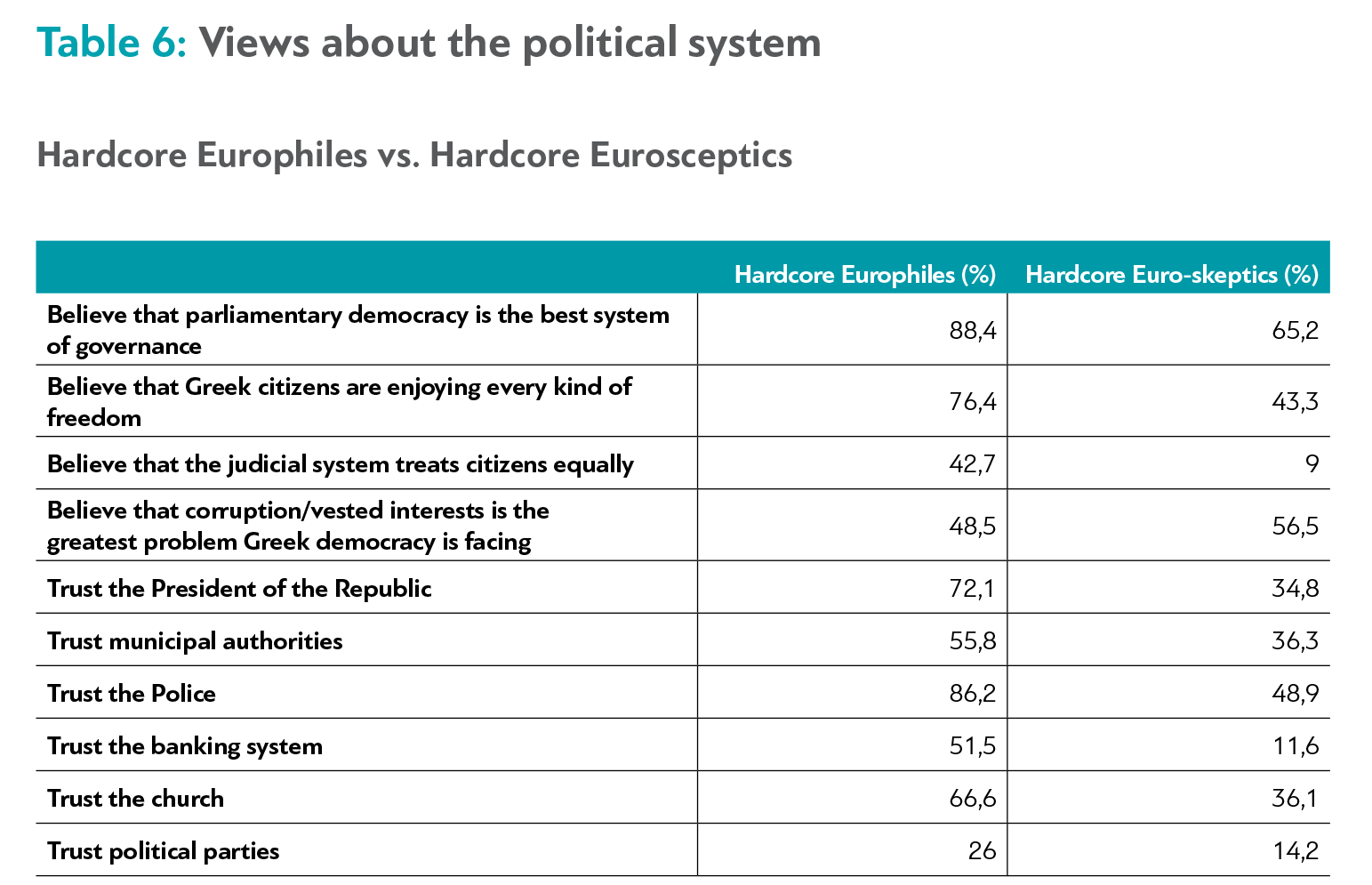

The data in Table 6 confirm that the cleavage between hardcore Eurosceptics and hardcore Europhiles determines political preferences to a significant extent. On the contrary, the Left-Right spectrum is not associated with the particularly differentiated views on the political system, democracy and institutions; that important dividing line appears to be weaker.

Summary

1. Support for presidential parliamentary democracy as a system of governance is very high (83.8%). However, that figure is notably lower than in the past (in a very similar question posed by Kapa Research in 2001, the respective figure was 95%). The 15.1% of the population that does not share the view that "parliamentary democracy is the best form of government" consists of a significant portion of the economically active population and young people. The excessive representation of the financial weak (with monthly income below €500), private sector employees and non-specialist freelancers within this ‘camp’ means that it has class features. Indicators of economic marginalization or economic failure tend to be expressed as disdain towards democratic parliamentary institutions.

2Hardcore Eurosceptics seem to have developed cynical attitudes and symptoms of alienation from the political system and its institutions; they represent a cohesive force in the country's political spectrum. This is a significant phenomenon whose importance has barely been assessed in Greek public debate.

3.The fact that the intermediate preferences along the Right – Left spectrum are losing ground is no surprise, especially in light of the collapse of old partisan affiliations. In one sense, the greatest surprise is the persistently stable (though weakening) major concentration of voters in the moderate positions along the political spectrum. This trend within the Greek political system survives despite the cataclysmic changes shaking the political party subsystem.

VI. The November 2015 Survey: Differences Compared To April's Survey

The survey of November 2015 confirmed all trends identified in the April survey. The protracted negotiations between the government elected in January 2015 and the European partners and creditors, the referendum of July 5 that same year, the imposition of capital controls, the signing of the third MoU and the elections of September 20, 2015 did not change the preferences of Greek citizens, despite the emotional swings and tensions in such an event-packed time. The differences noted are of degree, not quality, and they are related with a strengthening or a weakening of opinions and perceptions that had already been clearly recorded in the reference survey of April 2015.

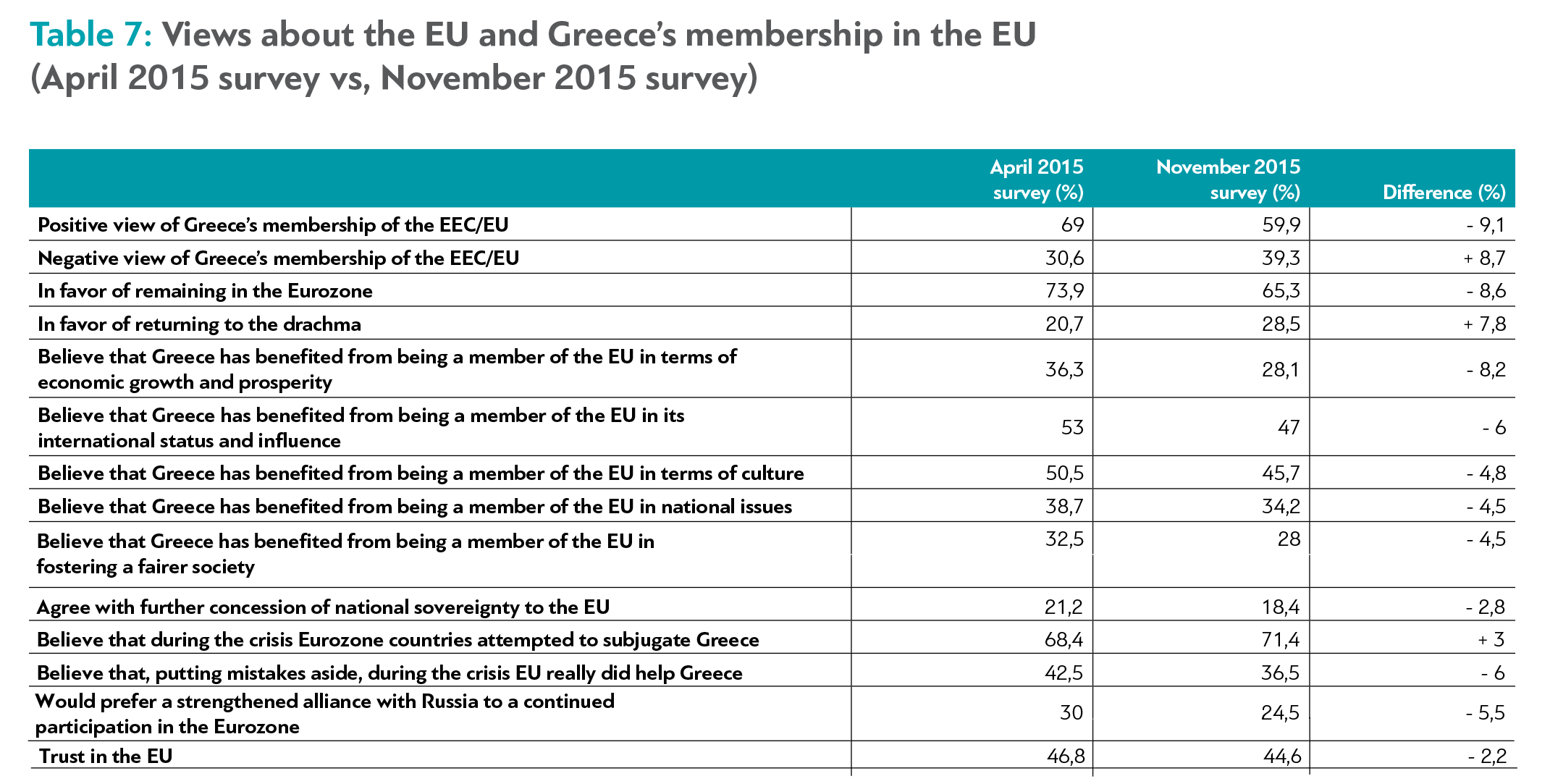

More specifically, the differences noted between the two surveys primarily focus on the "European issue". Views about European integration, evaluation of Greece’s involvement in the Union and about the alternative prospects for international alliances changed slightly but in a direction that simply served to confirm and bolster the research findings of April's survey. Table 7 summarizes the change in public opinion on these issues.

All the figures from the November Survey demonstrate a further boost of eurosceptic views.

On the critically important issue of the overall impression of Greece’s gains or losses from being a member of the EU, the rise in negative views is significant (positive views dropped by 9.1% and negative ones rose by 8.7%). The same was true on the question whether Greece should remain in the Eurozone (the figure for those in favor of remaining fell by 8.6 % -for those in favor of regaining monetary sovereignty it rose by 7.8 %). Overall, the majority continues to support the country’s European future, but all the figures from the November survey demonstrate a further weakening of the federalist spirit, a further rise in euro-realism and a further boost for eurosceptic views. At the same time, support for the prospect of strengthening alternative strategic choices (a hypothetical alliance with Russia, the USA or China) appears to have weakened. Seen from that viewpoint, Euro-realism has been bolstered in three ways: 1) the segments of the population that consider European integration as progress per se has declined, 2) segments that view EU policies in a negative light have increased and 3), the view that Greece should seek strategic alliances outside the EU has weakened. Greeks “love the EU less’ but at the same time, if one excludes the minority anti-European segment, they can see no alternative solution outside of it. The protracted negotiations between the SYRIZA government and the outcome reached by these negotiations bolstered Euro-pragmatism.

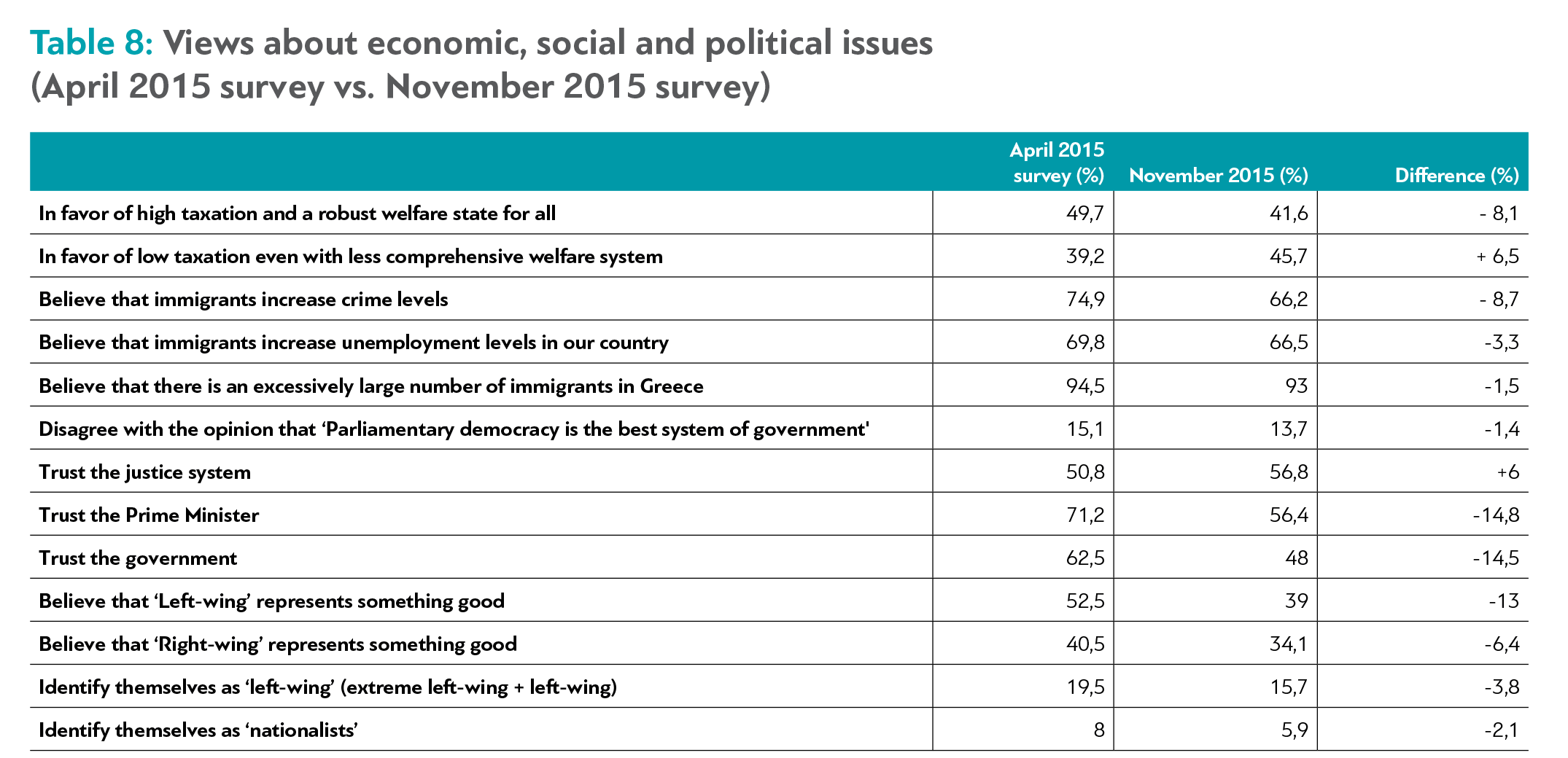

In Table 8 we highlight the most important differences on issues of economic and political preferences and the issue of immigration, which was beginning to be a major problem as the refugee crisis was deepening in November.

The first relates to a decline in the preference for "high taxation and a robust welfare state for all", which was a dominant preference in April. Clearly the increase in taxation during 2015 brought about a change in perceptions, with the result being that Greek citizens now prefer low taxation even if that entails a less comprehensive welfare state.

The second relates to the immigration issue. The overall perceptions have not changed at all between April (see section IV above) and November. However, despite the mass arrival of refugees and immigrants to Greek islands, and probably because of the human tide of misery, a slightly more favorable stance towards immigrants was noted. The overall picture of rejection remains dominant, but they express intense feelings and opinions of sympathy and tolerance towards the refugees. Another diaNEOsis study a few months later shows that the trend continued into 2016.

The third trend relates to narrow political preferences and opinions. The decline in positive opinions about the Prime Minister and the government, and in concepts associated with the Left, is due to the way of governance from January 2015 onwards. It reflects a pattern of reactions to political events which has been frequently observed in the past.

In short, the key research conclusions from the April 2015 reference survey (dominance of pro-Europeanism, a major shift towards Euro-realism, the consolidation of a relatively cohesive anti-EU camp, mixed economic culture with the dominance of economic liberalism, the dominance of cultural conservatism, rejection of key institutions of the political system) were fully confirmed by the November 2015 survey.

VII. General Conclusions

diaNEOsis’ major double survey (in terms of the number of topics investigated, and the size of the sample) attempted to take a snapshot of views and perceptions that elucidate the current ideological makeup of Greek society. In addition to measuring classic views and behaviors, the survey also explored the existence of any lasting values.

The survey puts forward a picture of all the preferences and the values of Greeks and moves beyond the emphasis on the ephemeral.

In these General Conclusions we will not reiterate the individual conclusions presented in each section above, but we will attempt to add some supplementary thoughts on them.

- In the 1990s and, partly, in the 2000s Greece has been a markedly pro-European country. That picture has changed radically. The change is both quantitative and qualitative. The significant drop in support for Europeanism in numerical terms has shifted the balance of power between the pro-European and the Eurosceptic camp, with the latter growing in strength. However, the pro-European camp continues to dominate and remains the majority view, in a way that is not open to any doubt.

- The qualitative change is more interesting and there are two sides to this coin. The first side is particularly important. Europeanism meaning "acceptance of and support for a supranational affiliation" is now undoubtedly a minority view and is limited to hardcore supporters (using the criteria and data from the November 2015 survey it is clearly limited to less than 20% of the Greek population). The European-wide decline in support for the European vision, which has been documented in the findings of the Eurobarometer, has now been documented to a very large extent in the case of Greece too. This shift towards a Euro-realism without a supranational vision is a major turning point in the history of the Greek pro-European camp.

- The consolidation of a significant and cohesive hardcore Eurosceptic group (which accounts for over 20% of the total population) is the second major shift in the preferences and values of Greeks. This is a group of people with a shared view of the EU and Greece’s place within it, as well as identical or similar views on the economy and the political system. Moreover, one of the most innovative findings this double survey has brought to light is that this group displays a distinct, comprehensive and internally coherent identity and it bears strong oppositional characteristics. This camp lacks any particular partisan voice (in the sense of robust, not necessarily uniform, representation). However, its presence has been clearly and distinctly recorded. As such, it represents a shift in the allocation of views and ideas concerning Europe. It is the second large shift in the European debate within Greece.

- The consolidation of the anti-EU camp is not ephemeral. Inherent to this trend is the dynamic of partial transformation of the Greek party political system. The emergence of the divide over "Europe" as particularly important in realigning not just European but also economic preferences, and those relating to the political system, is a powerful sign in that direction. The "comprehensiveness" of this divide reveals just how powerful it is. Similar trends have of course been documented all over Europe. If we assume that the conflict between pro- and anti-MoU forces contributes to the anti-Europeanism camp forging a better identity for itself, we can easily assume that its emergence goes beyond the conflict that dictated it and led to its establishment.

- The Right-Left divide, to a significant extent, determines citizens’ preferences on issues of economic values and on issues associated with cultural liberalism and conservatism. However, it exerts minimal influence on issues relating to the political system and a moderate influence on European preferences. Since it co-exists alongside other divides, it loses part of its ability to effectively divide. Clearly it is and will remain the central political dividing line. However, it is less determinative than in the past.

- The predominance of economic liberalism (and in part of neo-liberalism) in the context of a balanced economic culture with many social democratic elements and the lead held by culturally conservative values, demonstrate quite blatantly the distance between the narrow political sphere and the world of values. SYRIZA’s political domination was not accompanied by a significant change in citizens’ preferences and values.

- The relatively balanced coexistence of ideas and views drawn from different systems of ideas and political preferences, run throughout the findings of the survey. Greek society is a mixed culture society, where European ideas, economic liberalism, cultural conservatism and political cynicism dominate, but do not rule (with the exception of individual issues such as immigration). The co-existence and cross-fertilization of preferences makes it difficult to create one or two central head-on lines of conflict. The snapshot shows that there are distinct fault lines, which are active and –in relation to certain issues- deep. However, they do not tend towards the consolidation of a single central value-based conflict. This gives rise to a sui generis middle (but not intermediate) ground where left and right, progressives and conservatives, rich and poor, pro- and anti-Europeanists, traditionalists and modernizers can participate in varying degrees. Conflict and also complementarity as well as partial osmosis of value preferences lie at the foundation of this "middle ground". One illustrative example of this middle ground is the high regard in which the country is held (a small country with great cultural impact), an idea shared by citizens of all camps and hues. Better understanding of this ‘middle ground’ requires further investigation.

- The Greek identity is a battleground, just like any identity. Here left-wing views and values battle it out with right-wing views; neo-liberal views conflict with social democratic views; pro-European view with anti-EU views; culturally progressive views with culturally conservative or even ultra-conservative views; nationalist views battle it out with anti-nationalist views; the pro- and anti-Memoranda camps wage war and the optimists battle the pessimists. The Greek value system is divisive, contradictory; just like elsewhere in Europe. However, the impression created by the findings of this diaNEOsis survey is more complex: In the Greek identity battlefield, we do not have one side (whoever they may be) who battles out with one other side (whoever they may be). The battlefield is at the same time internal, and relates to the "average" Greek (so as to avoid the inaccurate phrase "every" Greek). That is perhaps an element which sets Greek culture significantly apart from the culture of many other countries. In one sense, the famed dualism of Greek culture, as described by Nikiforos Diamandouros12, does not accurately reflect the complexity of the value divides which mark –and define- modern Greek society. There is more than one type of dualism. At the same time though, that particular dualism exists. Diamandouros astutely points out that the rival cultural traditions stand out for their ‘pervasive nature’, i.e. their ability to cross –in almost horizontal fashion – “institutions, social classes, social layers and political parties”13. Dualism –some type of dualism- does in fact exist. It refers to a boundary that runs horizontally across all social groups and categories. It also refers to an internal boundary, an ambiguity, a division which individually affects most Greeks. diaNEOsis’ double survey emphatically highlights this inner boundary and this inner ambiguity.

Notes

1 The questions in Table 1 (save for a few insignificant changes) come from the Kapa Research questionnaire (2001) and correspond to questions 2, 14, 66 and 67 of this survey. Normally these topics are not addressed in well-established surveys, nor are they explored by Eurobarometer.

2 Since 1994 onwards Eurobarometer has consistently recorded that 65% to 80% of the population having a positive opinion about this matter.

3 In a 2001 Kapa Research survey with similar questions, the sense of gain in each sector was clearly higher than that identified in this survey, and the perception of loss was also higher. For example, Greece "is worse off in terms of its international position and influence" according to 14.3% of the population in 2001 and 23% in 2015, Greece "is worse off on national issues" according to 20% of the population in 2001 and 30.2% in 2015, and "in terms of economic development and prosperity" according to 16.8% of the population in 2001 and 38% in 2015.

4 The basis of our calculations were citizens who, of the 4 choices in composite question 9, opted to answer that it is vital for Greece to remain within the EU. 17.8% of respondents agreed with this view.

5 Our calculations are based on citizens who, of the 4 choices in composite question 9, opted for the answer “EU structures represent interests that don’t serve Greece’s strategic plans . Greece should leave the EU". 17.2% of respondents chose this answer. That percentage is higher in the survey conducted in November.

6 Negative views about the stock exchange are surely related with lingering trauma from its recent monumental collapse (2009), rather than some social democratic or leftist ideology. At present, these points are being evaluated without taking into account their original cause.

7 In the November survey this trend was reversed and the preference for a “low taxation and less comprehensive welfare system” was around 45.7% (see section VI).

9 The aforementioned views do not differ significantly, in all essential respects, from the corresponding findings of the years before the debt crisis. According to data from the polling company Public Issue, immigration is considered to cause increased crime rates in Greece (71% in 2008, 76% in 2009 and 75% in 2010) compared to 74.9% in this survey. According to data from the same company, on the issue of culture only, 38% in 2008, 32% in 2009 and 29% said that Greece benefited from immigration. Of course, in strictly technical terms, a precise comparison is not possible (due to differences in the questionnaires used) and an ‘inaccurate’ comparison is no comparison at all. It is noteworthy, though, that the magnitude is of the same order, while frequently –but not always- the anti-Memorandum trend appears to be increasing in strength as the years pass.

10 As far as the issue of building mosques in Athens is concerned, in a June 2009 survey by Public Issue 56% of respondents said they ‘completely agree’ or ‘probably agree’, which is a figure very close to the findings of this survey (despite the major differences in both the content of the question and the format in which replies were given).

11 The percentage of those who identified themselves as leftists or extreme leftists dropped in the second survey of November 2015 (see section VI).

12 Nikiforos Diamandouros, Cultural dualism and political change in post authoritarian Greece, Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales (CEACS), 1994

13 Op. cit.